When I first arrived in Korea, I was ready to eat my way through Korea’s diverse cuisine and make room for at least 27,400 different kinds of kimchi. While my dad compiled lists of Indian restaurants and grocery stores in Seoul for his ‘foreign student survival kit’ (as most fathers do), the thought of eating Indian food whilst in Korea made no sense to me.

But give it six months and I was craving my mom’s cooking, and the thought of Indian mango made my eyes well up.

Fuelled by nostalgia, I made my way to one of the surprisingly many Indian restaurants found around Seoul, but sadly I found none of the dishes I so badly wanted.

The words ‘tandoori’, ‘naan’ and ‘chicken curry’ were commonplace on every menu I scanned, but these dishes are specific to North Indian regions and aren’t actually consumed on a daily basis — the equivalent of going to Korean restaurants abroad and finding that the main dish everywhere is budaejiggae. Where is the kimchi? The rice? The myriad of banchan?

And so I decided to delve deep into why Korea eats only certain kinds of Indian food, and how this became the gold standard.

Mr. Ganesh, the owner of an Indian restaurant called ‘Aangan’, located near Yonsei University, had some great insights to offer.

He revealed that during his eleven years running Aangan, he’s had to add and remove several dishes from his menu based on his Korean customers’ response. For example, although roti is the most commonly eaten bread in Indian households, Naan seems to have become the most beloved Indian food in Korea.

Mr. Ganesh thought about introducing roti, but eventually decided against it.

“It’s quite crispy compared to naan and Korean people tend to not eat even the slightly hardened parts of naan, so I don’t think they’d like roti,” he explained.

I was surprised to find through my interactions with Korean people that they assumed all of India eats naan on a daily basis. As much as I would enjoy that, I’d soon start resembling the Pillsbury doughboy since naan is all flour and no wheat. Not only is naan much harder to make as compared to roti, but flour is also much more expensive than wheat in India. For the average Indian, naan is actually a luxury — eaten on family outings or special occasions.

Paneer or cottage cheese is another staple in Indian cuisine, but according to Mr. Ganesh many Koreans expressed confusion about this particular dish.

“Indian people love paneer tikka or shahi paneer, but for Koreans, paneer looks and tastes similar to tofu and they find it strange to see something resembling tofu served in this way [with Indian spices]. They don’t yet understand how we make paneer since it’s something we have to make from scratch [and it’s not sold in Korean stores]. So I had to remove that from the menu as well,” he said.

Then there’s the lack of South Indian food in Korea. A travesty, really.

While North India consumes more bread, the South fills up on rice — savory steamed rice cakes (idli), crispy crepes (dosa) both made of fermented rice flour batter and served with a variety of coconut-based chutneys and vegetable dishes, and so much more.

According to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, there are 11,000 Indian nationals living in South Korea as of 2017. Although it isn’t possible to map their cities of origin in order to correlate whether there has been an impact on the type of food introduced in Korea, Mr. Ganesh helped embolden some of my theories.

Theory 1: No South Indians in Korea? Or No Koreans in South India?

Surely there must be a community of South Indians in Korea, but it seems to either be smaller in proportion to the rest or they just aren’t into the restaurant business. I can’t blame them, the food business isn’t easy.

https://www.high-endrolex.com/34

Mr. Ganesh says, “I think the South Indian trend hasn’t yet come to Korea, but slowly it should enter Korea as well. There was a time when tandoori chicken wasn’t here either, neither was curry and naan, and it has just started slowly being promoted now. I think South Indian food will also be promoted here in the future.”

Then what about Korean people in India? Do they tend to visit South India less often in comparison to the Northern states?

Mr. Ganesh confirms. “Yes that is the case, those Koreans that do visit South India come here [to Aangan] and ask about idli and dosa — but it’s just two out of a hundred people, and we can’t sell for two people, can we?”

Theory 2: The Impact of Bollywood

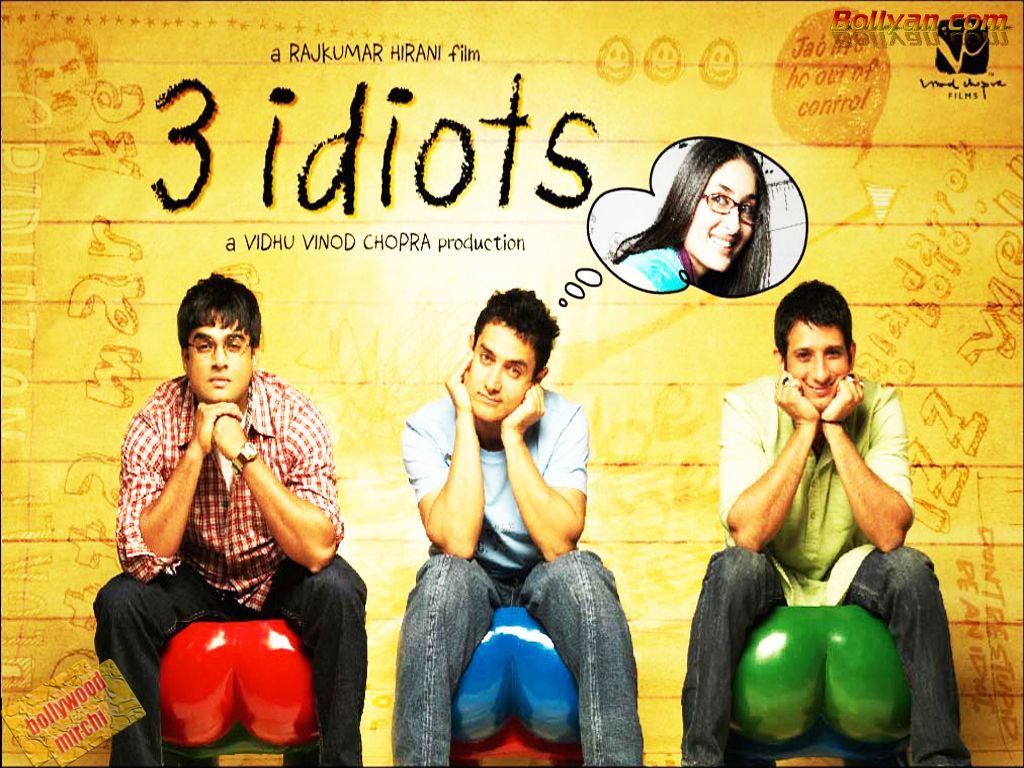

Every single Korean person I’ve met has at some point seen the Bollywood movie “3 Idiots,” and many of them have embarked on a trip to Delhi, where the protagonists attend university, and Leh, Ladakh due to the picturesque lake that serves as a background for the movie’s last scene. The movie has been deemed as one of the two most popular Bollywood movies in Korea, remaining at the Korean box office for 5 weeks upon release, and grossing over 3 billion won. The Korean movie “Finding Mr. Destiny”, arguably the most popular Korean film that features India as a backdrop, has also inspired Koreans to travel to India and follow the protagonist’s journey to Jodhpur.

Both these films feature Northern regions of India, and that’s not a coincidence. Bollywood movies, in general, tend to be focused on the North.

This is likely because Bollywood produces films in the Hindi language, and although it is one of India’s two official languages (the other being English), the constitution recognizes 22 other regional languages spoken all over India. While some of them are similar to each other, South Indian languages are vastly different, which is probably why they produce their own set of films.

The exposure of Northern regions of India in Bollywood films could be a factor that shapes Korean people’s perception of Indian food since South Indian films are yet to break into the foreign market.

But even then, are Korean people really consuming authentic North Indian food?

Mr. Ganesh caters to each individual customer by preparing fresh dishes taking their choice of spice-level into account.

“I’ve been running Aangan for eleven years now, the food we serve here isn’t 100% authentic Indian. We make a fusion style here because most of my customers are Korean and they can’t take all the spices and masala that we usually add to authentic Indian dishes. So I think that this restaurant is a good place for those new to Indian food as it isn’t a 100% Indian or Korean, it borders on fusion,” said Ganesh.

So he might say that it’s Aangan’s specialty to provide fresh food that caters to customers’ individual palates — something unique to his restaurant.

“That’s why I’ve been going strong for eleven years.”

While Indian restaurants in Korea might not cover the diverse range of dishes we consume, the formula they apply works for the Korean palate. Perhaps in time, South Indian dishes will begin to make an appearance in Korea and we might even see more regional dishes like those from North-East India on the menu.

For now though, since most Koreans don’t know what else is out there when it comes to Indian food, they can’t really miss it, can they?

In one year, I have gone from scoffing at the idea of consuming Indian food in Korea to begging a friend to bring me a six month supply of instant poha mix, a lemony flat rice dish that’s eaten for breakfast. Perhaps I should have taken my dad up on his survival kit, but let’s not tell him that.

I suppose it’s Indians like me in Korea that crave variety for now, and it’s up to us to let Korea know that there’s more to Indian food than tandoori chicken and naan.