More properly, we may speak of it (her status) as her want of position; for the principle is, in Korea, hardly more than a negation, and, like negations, generally has been most influential, not in what it denies, but in what the absence of it has permitted to take its place…for in Korea woman practically does not exist. Materially, physically, she is a fact; but mentally, morally, socially, she is a cypher.

- Chosun, The Land of the Morning Calm: A Sketch of Korea (1885), Percival Lowell (1855 – 1916), American astronomer, secretary to first Korean delegation to the USA.

- Extract from The “New Woman” and the Topography of Modernity in Colonial Korea, Jiyoung Suh, Korean Studies, Volume 37 (2013), page 12.

Korea (at the time called 조선 or ‘Chosŏn’) of the 1910s saw the emergence of the first feminists, ‘New Women’ (신여성). They were a new breed of women in unequivocal contrast to ‘Old-fashioned Women’ who were regarded as submissive housewives and childbearers under the control of traditional patriarchal Confucian hierarchy. Old-fashioned Women had very few opportunities for growth, mostly due to a lack of educational and travel opportunities. In this article we focus on the emergence of their nemesis, the New Woman and her radicalness, which was partly the cause of her demise.

“Wise mother & good wife”

There were some notable figures in the late 1800s who were part of a movement to herald in education for girls and women. Historically, China was Korea’s big brother, to whom it had to send tributes in order to obtain military protection and cultural imports (A Preliminary Framework, John K Fairbank). With Korean envoys being sent to China during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911/1912), China became its source to obtain Western ideas as an element of knowledge acquisition. After 1868, upon the establishment of the Meiji Restoration in Japan in 1873, emissary Kim Ki-su was dispatched to Japan to research into the introduction of the Western system for educating women, and documented his newfound knowledge in a travelogue in 1877. The writer, intellectual, politician, and independence activist, Yu Kil-chun had returned from a trip to the USA and was sharing similar information upon his return to Korea. Coupled with the Japanese development of education for girls and women as a part of nation-building, the momentum caught on in Korea and became a common discourse in newspapers during the late 1800s. They became the instigators of a new movement:

Girls are necessarily the children of Korean “people”….I hope the government will impartially treat people without discrimination by gender, generation, class, and the difference between rich and poor…Girls will be the wives of men, and if they are as knowledgeable as their husbands, the family will be prosperous.

- Excerpt from Tongnip sinmum (독립신문 or ‘Independence news’) newspaper, May 12th, 1896. From an article titled An Argument on the Education of Men and Women.

- Extract from The “New Woman” and the Topography of Modernity in Colonial Korea, Jiyoung Suh, Korean Studies, Volume 37 (2013), page 15.

Newspapers commented on Western women as being of equal status to men, contributing to the household by educating their children, as well as managing household matters with their husbands – working together to flourish as a family. In comparison, a Korean newspaper in 1896 described Eastern women as “the slave of man” – only being able to take care of simple household chores (Tongnip sinmum 독립신문 or ‘Independence news’ newspaper, April 21st, 1896. From The “New Woman” and the Topography of Modernity in Colonial Korea, Jiyoung Suh, Korean Studies, Volume 37 (2013), page 15).

Korea desired to catch up with Western countries and acquire modern knowledge. The Japanese had wanted to educate girls and women so that they would be mothers who could educate the next generation, hence creating the manifesto, “good wife and wise mother.” Koreans adopted the same principle, but reversed this to their preference of “wise mother and good wife.” A better ability to converse and understand their husband’s work was an added bonus. This principle became a standard policy in education in girls’ schools upon the start of Japanese colonisation in 1910 and was the beginning of a major cultural transformation.

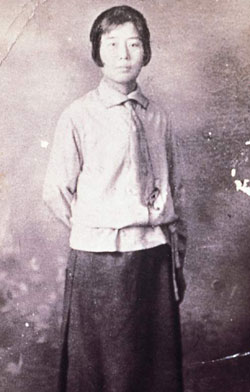

Na Hye-sok: beyond her time

Na Hye-sok. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Education for girls would later backfire on the Japanese, as the same girls that had been educated would be participating as student protestors in the renowned March 1st, 1919 Korean Independence Movement. In a publication called Hakchigwang (학지광) in November 1914, the male-made ideology of “wise mother and good wife” was challenged by Na Hye-sok (1896 – 1948), a female writer (The “New Woman” and the Topography of Modernity in Colonial Korea, Jiyoung Suh, Korean Studies, Volume 37 (2013), page 19). She argued that it was a patriarchal ideology designed to create compliant women, who would just be a more refined version of men’s own previous obedient wives.

The late 1910s saw the emergence of women’s magazines, with Yeojagye (여자계, called ‘Women’s World’) being founded in 1917, followed by Sin Yeoja (신여자, called ‘New Woman’) in 1920. Na Hye-Sok, who was becoming a renowned and radical feminist of her time was one of the contributors, writing about the need for Korean women to wear more comfortable garments instead of their restrictive traditional wear. Alongside her career as a writer, she was respected as the country’s first female Western landscape painter. As an exemplary New Woman herself, her life was a reflection of what they stood for – 1) Spiritual and cultural liberation of women through education. 2) Expressing one’s rights in both private and public arenas. 3) Having received a modern education and imbibing a Western consciousness.

Na Hye-sok had come from a financially privileged background and was able to obtain an education in Japan majoring in Western oil painting at Tokyo Arts College. Other New Women often studied in countries such as Japan, Russia, and China. After participating in the March 1st Independence Movement in 1919, she was imprisoned; her family sent her a lawyer to represent her in court and she eventually married him, displaying a rare “love marriage” during the days of predominantly arranged marriages. Na Hye-sok had placed conditions on her husband in order for them to marry, this included; to not stop her from painting, and to not make her live in the same house as his mother and his daughter from his previous marriage. In addition, upon her demand, on their honeymoon, they visited the grave of her former lover, and he helped her to build a monument for her ex. In 1927, they embarked on a tour of Europe and the USA. She would write travelogues and paint landscapes while in the West. One of her experiences included staying with a couple in Paris. She recalled how the couple would openly kiss each other, and sometimes leave the children at home to go on dates to the cinema during evenings, and her experience of watching dancers in Moulin Rouge exposing their bare bellies. It was a world of stark disparity from her native land, where romantic love was not openly expressed and bodies were not exposed.

During her time in Paris, she met Choi Rin, a leading social activist in Korea in the 1920s (who went on to becoming pro-Japanese); their friendship soon metamorphosised into an affair. However, she told her husband about it and that was the end of the story. Unfortunately, upon her return to Korea in 1929 her rendezvous in Paris became known because of Choi Rin, resulting in a scandal. Her husband divorced her, she lost custody of the children, and she was ostracised by her family and friends. Na Hye-sok refused to take this passively though. Firstly, she demanded financial compensation from Choi Rin for her losses, and secondly, she wrote a piece for a magazine titled, A Confession About My Divorce (1934). In this confession, she condemned the double standards imposed upon Korean women, in contrast to Korean men who were never subjected to any humiliation due to affairs and trysts with kisaengs (courtesans providing company and artistic entertainment to men).

In her later years, she moved to a monastery where she continued her painting. Na Hye-sok tragically died on a street alone, desolate and poor. She was a future female body trapped within an archaic past. Her short story, Kyonghui (1918) is a revealing portrayal of the mindset of a New Woman.

Kyonghui; reality & fiction intertwine

In a similar fashion to Na Kye-sok, Kyonghui features a New Woman protagonist named Kyonghui, who has just returned from Japan to her family in Korea for the holiday season. Upon arrival, we learn that she is ardent with housework. Kyonghui was executing what the uneducated Old-fashioned Women would normally have done, however, she did not labour from a space of obligation and expectation, but with zeal. She had learnt how to work more methodically and add a touch of creativity too. The impetus was different from her counterpart.

“It seems that no one is satisfied with the life that’s available to them. Everything depends on the state of one’s mind. One learns how to find satisfaction in life while engaging in the day-to-day tasks of earning money, doing business, or acquiring knowledge. That is, one feels content only when one sees the presence of God between people and objects.”

– A Confession About My Divorce (1934), Na Hye-sok

Later in the story, we learn that she had previously rejected her father’s request for her to marry a suitor of good breeding. As time had passed since that proposal, her parents became concerned about her future as an unmarried woman, which led her father to put Kyonghui into a compromising situation; to stop her studies and marry a man that he had selected from a well-respected family. She was torn between her filial duty as a daughter, and her yearning to be emancipated from the system. Through her discomposure, she arrives at a breakthrough, transcending what it means to be both Korean and a woman:

“First of all I am a human being. Then I am a woman. This means that I am a human being before being a woman. Moreover, I am a woman who belongs to the universal human race before being a Korean woman.”

– Kyonghui, Na Hye-sok, pages 50 & 51

Both Kyonghui and Na Hye-sok were anachronisms who did not belong in contemporary Korea.

An illustration by Na Hye-sok unrelated to Kyonghui. Depicting a New Woman diligently making time for both housework and study within a day. Source: Semantic Scholar: Creating New Paradigms of Womanhood in Modern Korean Literature: Na Hye-sok’s “Kyonghui”

Mid-1920s to mid-30s: New Women as threat

For educated Korean men and intellectuals at the time, New Women were their classmates and companions, which sometimes naturally led to dalliances. However, traditionally Korean men had to marry at an early age of approximately 15 or 16 years of age, before entering university. Sometimes even as young children, their parents had selected their spouse to be. These women were usually Old-fashioned Women, resulting in a conflict of interest, as the men could instead engage in discourse with women matching their intellectual capacity in a scholarly college environment. The affairs that resulted became one of the attacks on New Women. The mid-1920s saw the emergence of clashes between women’s liberation and the male-constructed notion of “wise mother and good wife.” New Women were concerned about individual cultural and educational growth, and liberation from suffocating patriarchal structures. However, through the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), with nationalism on the rise, national liberation and progress were viewed as issues that were of far more importance as the “we” of Korean citizens. In contrast, the “I” centred perspective of New Women was opposed by nationalists along with their careers, progressive ideas, and Western attire.

New Women were under attack from men who were in positions of power. Images of them as being promiscuous and having a lifestyle of excessive consumption placed them as the abject during the Socialist movements from the mid-1920s. Chastity for unmarried women was highly valued in Korean culture at the time. There existed a pseudo-scientific belief that with each man that a woman had sexual intercourse with, a part of his blood would enter her, ultimately resulting in her baby being an amalgamation of all of her sexual encounters (New Woman, Romance, and Railroads: The Paradox of Colonial Modernity, Kelly Jeong, Acta Koreana (2007), pages 9 and 10). Accusing New Women of being promiscuous was viewed as a strong offensive from men.

Simultaneously, the image of the New Woman was overlapped with that of the Modern Girl, a new type of career woman. Often working in the urban service sector, she desired to live a ‘modern’ life attired with the latest fashion. However, what differentiated the Modern Girl from the New Woman were the following factors: 1) Emancipation through modern/Western thoughts through consumption and attire. 2) Emancipation via equal rights with men – to live equally and independently through work and enjoyment. Modern Girls lacked the education as well as the modern consciousness that New Women had assimilated. Even though these two types of women were different, in the 1930s, through media, they were merged and depicted as women of excess and again, in pursuit of sexual freedom. This was one of the nails in the coffin for New Women. Korean nationalists and intellectual males desired a return to motherhood and longed for the servitude that the original Old-fashioned Women provided. Therefore, the antithesis of the New Woman; the overhauled Old-fashioned Woman equipped with modern education, became a “wise mother and good wife” fused with modern knowledge on parenting, hygiene, and home economics, was welcomed as the “perfect” woman.

Her legacy & successor

The final factor to the New Woman’s passing had also emerged in the early to mid-1920s during industrialisation. As greater numbers of young women moved from rural areas to cities in search of employment, a significant number experienced sexual harassment and rape in the workplace – often in factories. Coupled with the rise of anti-Japanese nationalism and socialism, a new trope was born, the Socialist Woman. These were working-class women, who did not have the luxuries of foreign education and (female) servants like New Women. They were servants to an emerging capitalist system, and were in the process of heralding in a new era of feminism.

Literature by Na Hye-sok and her fellow female writers during this era demonstrates a clear conveyance of New Women from Old-fashioned Women, and unlike popular belief, feminism in South Korea harks back to the 1910s.

She and her fellow New Women were what contemporary men may have viewed them as at the time, Frankenstein-esque – a malfunctioned product of their own making. Their desire to revamp their subservient wives through modern education may have been successful, but it also resulted in this creature deemed as the New Woman, running amok from their initial envisioned task. The 1930s ushered in a return to conservative ideologies, in contrast to the feminist expansions that had taken place during the 1910s and early 1920s. Even though New Women may have been viewed as spoilt, self-centred bourgeoisie by the later Socialist Women, they were the first to confront male-dominant ideologies and forge a path of their own towards female emancipation.

A special thank you for their illuminating insights to Professor Shin Jeeyoung from Yonsei University, Jang Youngeun – the author of ‘Na Hye-sok, the birth of the Korean female writer,’ Suh Ji-young – the author of ‘The “New Woman” and the Topography of Modernity in Colonial Korea, Kelly Jeong – the author of ‘New Woman, Romance, and Railroads: The Paradox of Colonial Modernity,’ and Kim So-young, the director of the documentary film, ‘New Woman: Her First Song’ (2004).

Feature image of Na Hye-sok obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

- Emasculated: Angry Men in Korean New Wave Cinema - March 17, 2023

- Urban Subversion: 6th Generation Chinese Cinema - February 3, 2023

- Seoul: Post 1960s Genderised Cityscape - December 2, 2022