On the day of Yonsei’s 137th anniversary celebration, I went to a protest. It was organized by Yonsei’s Korean Language Institute (KLI) and the theme of the protest was the death of Yonsei’s education philosophy.

The KLI teachers wore all black like it was a funeral and played traditional funeral music. They spoke about how although someone could not resurrect a dead body, a dead school could be saved.

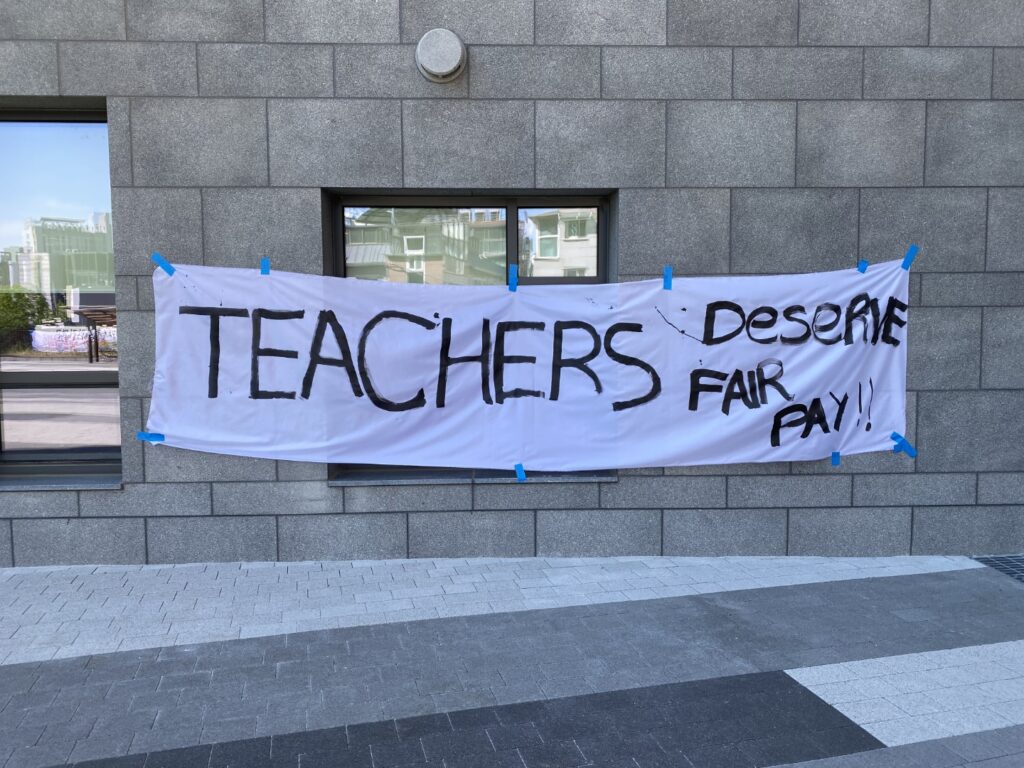

We sat outside the main building on the ground as teachers gave speeches. We were handed signs with slogans to chant and as university administrators left the building to head towards another area for lunch, we trailed behind them and camped outside. Teachers handed out papers to passersby that detailed why they were protesting.

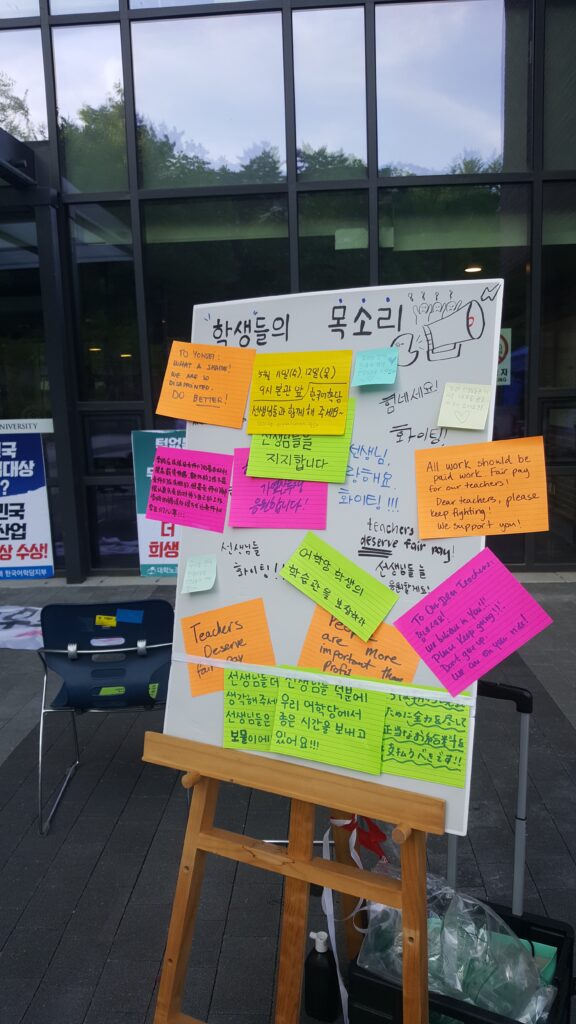

Students trickled in, joining the teachers and other students sitting on the ground. Several made signs and wrote in their native languages.

Their signs had assorted messages:

“Yonsei University’s Education Philosophy is dead”

“We love our teachers”

“Don’t see international students as a way to make money”

The history of Korean language programs

In 2015, as most foreign language enrollment was on a sharp decline in the United States, one language was outperforming by a significant amount: Korean. While other languages were proof of the decline of international studies, dipping by almost ten percent, Korean language enrollment had an increase of 40%.

It seemed as if the wild success of Hallyu, the Korean wave of pop culture, was translating into Korean language enrollment. Soft power advocacy was working; people were taking time to learn about the actual language and engaging with more than just pop culture.

As the aphorism goes, “a rising tide lifts all boats.” This is true in the sense of Korean language programs; the industry saw an increase in income as Hallyu has exploded around the world. But under the blatant success there is a dark truth.

Most Korean language teachers in the country as well as globally have low wages, an unstable work status, and poor working conditions. Such is the case of Yonsei’s Korean Language Institute (KLI). Established in 1959, the award winning institute was the first to be established in the country. It has its teachers to thank for its excellent quality of education. And yet, it has repeatedly ignored teachers’ demands for better wages.

Most students at Yonsei’s KLI were unaware of their teachers’ position. They enrolled to Yonsei’s program expecting that the reputation of the university would guarantee quality education as well as proper respect towards both educators and students. And for the most part, previous students who attended over the years have glowing reviews of their teachers and their experiences.

But this year, everything changed. This year, students were directly impacted by the university’s reaction to the teachers’ protests.

Disruption

I learned first about the protests through a friend who is a KLI student. She and other KLI students got a sudden email a week before finals that there was a change in the format of the exam.

Usually, exams cover all the foundations of language: reading, speaking, writing, and listening. Speaking was erased for the exam and the format was now going to be run over Zoom with each level crammed into the same room, resulting in up to over 200 students per room. And worse, students’ final grades became fully dependent on the results of the final exam because the midterm grades wouldn’t be accepted. This had very real consequences for KLI students whose visa status was now fully singularly dependent on their final exam grade.

Yonsei KLI said it was because teachers were on strike and part of their strike was to not return midterm grades. This was a blatant lie that students and teachers alike quickly refuted; everyone got their midterms grade. And yet, by blaming teachers for the sudden change, Yonsei KLI absolved themselves of any responsibility.

In fact, the new format of the final exam cut out the need of the KLI teachers themselves. It was not going to be facilitated by a teacher or graded by a KLI teacher; it was going to be administered by someone who didn’t work directly with KLI students. KLI is composed of three types of employees: teachers (who are the bulk of the program), full time lecturers, and administrators. The full time lecturers and administrators administered the program, rather than the teachers who historically have done the job because they work directly with the students.

In short, Yonsei KLI’s response to their teachers’ demands was to completely cut them out of the program. By changing the format of the finals as well as scrapping the midterm grades, teachers were no longer needed.

And the final exams were chaotic. The facilitators were late to several sessions, did not enforce students turning on cameras, and did not make students turn their microphones off. The listening exam was especially rough with audio mixing up students who were already stressed listening for a foreign language. And the facilitators lost half of Level 3’s listening scores and made the students retake the exam during their rest time.

Yet through this all, Yonsei KLI remained unreachable. Teachers repeatedly apologized to students though it was none of their fault and urged students to contact the KLI administration. Only a select few students got responses that did not address the issue and the rest were ignored.

The KLI students were confused at what was happening. Many students came from abroad and expected a quality education that would be consistent with what was promised to them. And for the most part, the students I spoke to spoke very highly of the KLI teachers and how they taught and more importantly, cared for their students. But as the students got directly impacted by the unresolved situation between the teachers and Yonsei KLI, they learned what was happening.

Yonsei KLI teachers’ history

Last year, Yonsei KLI teachers started publicly protesting about their wages. Their main demands towards the school was for higher wages as well as payment for out of class work. According to an article which was run in the Yonsei Annals last year, the conclusion was that as of August 11, 2021 the labor union was planning to pursue arbitration at the National Labor Relations Commission.

However, a year later, the situation remains with many and more similar signs cropping up once again on Yonsei’s campus.

According to the spokesperson of the Yonsei KLI Union, last December the university and the union started negotiations but didn’t reach an agreement. Therefore this year on April 15th the teachers began industrial action. The union organized a mix of events, inviting students to write on post it notes at the Miwoo Building, holding a conference where students gave speeches, and protesting in front of different Yonsei buildings. They covered the inside of Miwoo Building’s elevators with pictures of texts from students that expressed frustration towards the program and support for the students.

Nothing happened. Still, the union held onto hope.

The Yonsei KLI Union was created in 2019 and did make progress. The teachers fought for increased allowances and in 2020, there was a slight increase in wages as well as including prenatal examination hours and infertility treatment in paid vacations.

But before the union was formed, there was no change in wages. As in, during the span of Yonsei KLI’s sixty years of existence, there was no change until the teachers began to advocate and fight for their rights.

Last year the union created their Instagram account to more publicly share and update their progress. They’ve been more openly sharing with students about the situation, apologizing along the way and translating news in at least English, Chinese, and Japanese.

To lay out the full history, teachers also sent students a letter describing the situation. In it, it gave the rundown of the situation as well as statistics. Yonsei KLI teachers got the least salary despite the program’s tuition being the highest in the country. In fact, the tuition increased by 11% in the 2022 spring semester. And Yonsei KLI took 46% of the teachers’ income in the name of overhead which most suspected went towards renovating the Miwoo Building. The hours teachers spent to prepare for class, grade, and create tests were not paid.

Students were shocked. This was a far cry from what students expected and some immediately penned emails towards the program, expressing that they felt that their trust was broken. They felt like Yonsei KLI did not care about the financial burden of students because, as one student said, it’s much easier for a university to recover financially than a student. They felt like they were seen as a statistic rather than actual people. And they felt like Yonsei KLI was forgetting that these students were entrusting their time and money to the program for the sake of their education and futures.

Currently

As of May 28, the Yonsei KLI Union has started visiting external institutions to resolve the issues at hand. They have so far visited the Foreigner Management Office as well as the Sejong City Government Department of Education. And people are taking notice; at the May 18th strike, Seoul National University student reporters spoke with those in attendance and a labor attorney also spoke to the strike to give them guidance.

The KLI Union also knows that there have been complaints about the noise of the protests. “Know that we have no choice but to make a noise,” the spokesperson said. “We need the support of the students, employees, and professors.”

“Many say that the role of Korean language teachers is important when talking about the excellence of K-culture, but our work environment is not good. This is a global issue. We want people to know what it means to be a Korean teacher. ”

Writer’s note: As of June 29, the Yonsei KLI Union has been in intensive negotiations with the school since June 23. Updates are shared through the union’s Instagram.

- “Our teachers deserve better”;Yonsei KLI Teacher Protests - June 30, 2022

- Translating Veganism into a Korean Context - June 9, 2022

- The Meaning Of Flowers - May 6, 2022