Female mobilisation for the building of the Korean nation has been a recurring theme in modern Korean history, and particularly depicted within film and literature. Industrialisation first started from the mid-1920s, during the Japanese colonial era (1910-1945). Droves of working class women migrated to urban areas as bodies for the machine age, sometimes to discover inadvertently that they would also be used as objects for men’s pleasure. During the 1920s and early 1930s, two of the largest demands during strikes by female factory workers were for higher wages and an end to sexual violence.

Following the Korean War (1950-1953), after many men were either killed or disabled, women often sought work and became the breadwinners of the family. After the dictator, Park Chung-hee’s coup d’ete in 1961, he set about with the modernisation of South Korea, in which thousands of women again, left for cities to seek employment in light industry factories. On a mission to earn money, some women encountered sexual harrassment in the workplace, and unforeseen situations led them to sex work. This article focuses on six aspects related to this: 1) Rural to city exodus & filial duty. 2) 1970s sex tourism 3) The new ‘hostess’ genre. 4) A focus on Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975) as a representative film of the ‘hostess’ genre. 5) Cinematic depictions of prostitutes through the male gaze. 6) Female sacrifice for the nation.

Rural to city exodus & filial duty

The 1960s and 1970s saw an exodus of people, particularly women moving from rural areas to cities for employment during rapid industrialisation. In 1960, there were 26.8% of female labourers in this exodus. In 1976, this number had increased to 45.7%.

From 1961 to 1981, the GNP tripled from $471 to $1,549. The primary exports from South Korea were textiles, garments, agriculture, fishery, and mining. Working class women and girls were key components to the growth of South Korea into a modern, wealthy nation, with over 1,000,000 of them working in the light manufacturing industry all over the country.

For women and girls deriving from rural areas, it was often viewed under traditional Confucian culture, as filial duty for daughters and sons to sacrifice themselves for their often poor families. In the case of women, they were expected to send savings back home to support their parents financially and sometimes to help their male siblings to enter school too, even though the sisters had not been able to receive an education at a level on par to their brothers. Moving to cities and seeking work was also a way for them to gain social and financial independence away from their families and domestic work (Lee, 2010: 86).

These women and girls were often called mujakjong sanggyong sonyo (무작정 상경한 소녀), which translates to “a girl who came to the capital without any plans.” Relatives or friends who were already residing in the city were often a gateway for them to get their foot into the city through initial help and/or accommodation. Factory work, domestic labour, becoming sales assistants, and bus conductors was the norm. Those without contacts in the city would be taken in by employment agencies who advertised their services in newspapers (Lee, 2010: 86).

Unfortunately, there were many cases of women who had been sexually harrassed in their new workplaces away from their families and homes. These stories reached mass media through tabloids, TV, and film. On top of sexual harrassment and rape, some women found themselves unable to make enough money, had harsh and dangerous working conditions, and realised that they could not achieve their dreams as independent working women. Sex work proved to be the only option within a world of uncertainty and rapid change.

For some women in working class positions, doing sex work on a casual basis was a means for them to supplement their low income. These part-time sex workers had more choice in who their clients were, what hours they worked and how much they charged, compared to those who worked full-time in prostitution districts. In some professions, such as massage parlours and barbershops, there was a thin line between the actual advertised service and additional paid sexual services, which were encouraged by employers (Lee, 2010: 87, 88). Transitioning into the sex industry also became smoother, as the government was implementing laws to make sex work legal.

1970s sex tourism

Even though this article is focusing on women who became prostitutes unintenionally, it is worth noting that during this period of modernisation, the Park Chung-hee government was setting various wheels in motion for the accumulation of national capital. One of them was by sending troops for the Vietnam War and earning additional finances through high American dollar payment. Another method was through the establishment of laws and regulations to promote sex tourism in the 1970s, in particular to Japanese men.

In contrast to the 1961 “Laws on the Prevention of Prostitution,” special work permits were issued for prostitutes to work in hotels to serve foreign tourists in 1973. In 1972, the number of Japanese tourists was 96,531. In 1973, this jumped to 217,287. Women were not just cheap labour in factories, but also within the sex industry. The introducton of these changes in law, allowed the government to save money on state expenditure, as sex workers could earn their own money and send savings back to their families in rural areas. From the late 1960s onwards, large segments of Seoul were being turned into red-light districts.

1970s South Korea witnessed amongst other industrialising nations, the introduction of what the American sociologist and feminist Kathleen Barry called, the “industrialisation of sex.” This was a different method of Japanese state-sanctioned sex work of the comfort women of the 1930s and 1940s during the Japanese colonial period. Comfort women were women and girls (up to 200,000 in number) from mostly Asian countries, including Korea, and some from the Netherlands, who were forced to serve as sex slaves for Japanese soldiers. In the 1970s, the South Korean government implemented a plan to commercialise and commodify female working class bodies as part of the machine of rapid industrialisation. The ‘hostess’ genre, which emerged in 1974 was a sign of the times.

The new ‘hostess’ genre

South Korean cinema hit a low point during the 1970s due to strict state censorship. The government renounced content, which portrayed life against ideal national development and presented poverty. However, the ‘hostess’ genre films were able to pass censorship by making amendments and shooting plus editing the films in a certain manner, which will be looked at later on in this article. They went onto becoming box-office hits and rebooted the film industry. These ‘hostess’ genre films were sometimes filmed in real prostitute back alleys and brothels, and around US military camps where red districts were common. One of the representative films of this genre is Yeong-ja’s Heydays (1975).

Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975)

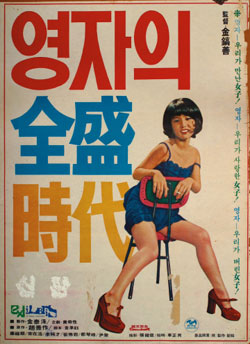

Poster of Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975), by Kim Ho-sun. Source: MyDramaList

The film depicts the life of a working class young woman, moving to a city, trying to survive through various menial jobs, and finally becoming a prostitute due to a series of unfortunate circumstances. The film became a box-office success. As Kim writes in her essay, Genre Conventions of South Korean Hostess Film (1974-1982): Prostitutes and the Discourse of Female Sacrifice, Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975) features a plot which was closely connected to reality for some working class women and girls at the time: the girl/woman leaves home, she has a series of mundane jobs, which cannot provide financial stability, she has a major accident in the workplace, gets raped, becomes a prositute to earn more money, and in the process she gives up the love of her life as she no longer feels worthy enough for him.

Like other films in this genre of the era, the protagonist, Yeong-ja, is never depicted as a fallen woman that should be ashamed of herself. Her falls are clearly shown, and she is an honest and selfless individual. After receiving financial compensation for her work-related accident, Yeong-ja immediately sends all the money to her poor family in the countryside. As Kim writes in her essay, this film could be compared to the Weimar era films (1918-1933) from Germany, in which prostitutes were often depicted as “holy public figures, selfless…liberate people from sexual and moral contraints.”. In addition, the commodification of women’s bodies during the Wiemar period during modern capitalist society is similar to what was happening during South Korea’s rapid modernisation period in the 1960s and 1970s.

Spoiler alert: Even though her boyfriend continuously forgives and accepts her choice of living, she rejects him and chooses to marry a poor disabled man instead. She believes that she is not good enough for her actual love and that she would be an obstacle for him to realise his dreams. At the end of the film, her former lover spots her living in a shanty town. They reunite, he is introduced to her husband, and the two men proceed to go for a drink together on their motorbikes. The ‘happy ending’ is less about Yeong-ja, and more about the successes of these two men. Her existence is brought down to serve the men in this patriarchal-pleasing climax, leaving the audience wondering who’s heyday the film is actually depicting. Yeong-ja’s pleasing of these men on the micro level, is simultaneously representative of South Korean women yielding themselves to serve the male-driven nation on the macro level.

Cinematic depictions of prostitutes through the male gaze

As mentioned earlier, certain stylistic decisions had to be made in order for Yeong-ja’s Heydays to pass censorship. One of the main ones was of close ups of the prostitute’s body and face, fetishizing and recontructing her into an object. This made the film hyperrealistic in parts. Yeong-ja is emotionless during sexual activity, even with her boyfriend. The manner of filming and editing is both an exploitation of these working class women’s bodies, and a method to satisfy the male gaze.

Sometimes sound is omitted during scenes of her in sexual intercourse, which reduces her down to even more of an image; real but also not quite real. A fantasy for the male to objectify and tame the female body.

Prior to Yeong-ja’s disabling accident, she is raped repeatably by the owner’s son, while working as a housemaid. During the initial rape scene, the POV (point of view) is of the male rapist, while we see her below us, the camera, as a helpless and powerless victim. This emphasises the man as the subject and Yeong-ja, the woman, as the object.

In the first shot of the film, there is an alleyway with prostitutes being caught by policemen. The women’s voices are muted. They are silenced as the policeman’s POV dominates them with added effect by the placing of policemans’ domineering hands on the dominated female bodies.

Policemen arresting a prostitute in a red-light district in the film Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975), by Kim Ho-sun. Source: Beat Pyeong on YouTube

Female sacrifice for the nation

These prostitutes, including Yeong-ja in ‘hostess’ genre films are shown as innocent and wholesome women who are putting themselves on the sacrificial peer for the sake of supporting their poor families, educating their brothers, as well as serving as commodified beings of a newly created expanding capitalist regime. Common to this particular necropolitical occupation across the globe, the possibility of death is always near (Lee, 2010: 82), so in the same fashion, these women’s lives are ended through sickness, going missing, or death. In the process of filial duty, Yeong-ja is degraded by being raped several times, literally losing an arm, and ending up working as a sex worker as a method of survival within newly industrialising South Korea, and for the well-being of her impoverished family.

In a culture where female chastity was expected and respected, these sex workers were outcasts of society, yet served as necessities for men of a patriarchal nation, who believed in the “angel” wife and mother no longer being able to please her husband sexually after giving birth. Hence, the need for an alternative (still a valid topic for the 2020s). They were necessary but devalued consumables within a growing capitalist nation. Female factory workers and sex workers could relate to Yeong-ja’s Heydays: “Roh’s analysis of Young-ja indicates that the original book and the film were both consumed by large numbers of female factory workers and sexual workers.”

The ‘hostess’ genre is an important aspect within the one-hundred-plus-year rich cinematic history of Korea, as it extends out lived realities of a certain type of working class woman, who lived within a specific socio-political era of South Korean history. Through this genre, one can more deeply fathom the sufferings which certain individuals had gone through, and how their role as sex workers was part of the bigger map of modernisation.

In addition, through this genre of films directed by men and sculpted to pass authoritarian laws, one can view and examine the objectification of working class female bodies through the scopophilic male gaze.

Ultimately, as depicted through the cinematic style of the film, the Korean prostitute’s downfall is for the pleasure of men, which in turn equals the pleasure of the national patriarchal eye. Yeong-ja’s Heydays and films of the ‘hostess’ genre from 1974-1982 are indicative of working class women during this period serving “the greater good” for the transformation of South Korea into a modern nation. Film production companies jumped on the bandwagon of the ‘hostess’ genre trend at the time, but have also left us a historical trail of a significant development towards the current successful capitalist South Korea that we know. Post-1982, the tables started to turn in the 1980s and 1990s, in which a new generation of South Korean women started to become sexually emancipated.

The main image in this article is from Yeong-ja’s Heydays (영자의 전성시대) (1975), which was used in an exhibition by STEAK FILM, titled Recurring Visions: Mythology, Women & the Concept of “HAAN” in Korean Cinema. The exhibition took place at Cinema Galeries in Brussels, Belgium in 2019.

A thank you to the following authors for sharing their research and knowledge:

1. Genre Conventions of South Korean Hostess Films (1974-1982): Prostitutes and the Discourse of Female Sacrifice, by Molly Hyo Kim.

2. The Concept of Female Sexuality in Korean Popular Literature, by So-hee Lee.

3. Tales of Seduction: Factory Girls in Korean Proletarian Literature, by Ruth Barraclough.

4. Domestic Prostitution: From Necropolitics to Prosthetic Labor, by Jin-kyung Lee.

- Emasculated: Angry Men in Korean New Wave Cinema - March 17, 2023

- Urban Subversion: 6th Generation Chinese Cinema - February 3, 2023

- Seoul: Post 1960s Genderised Cityscape - December 2, 2022