The sudden death of Kimura Hana, a professional wrestler, and cast on the popular Japanese reality show Terrace House: Tokyo 2019-20, has thrown light on a rise in the abuse of online space and kindled national debates about this issue. As someone who has enjoyed the Terrace House series for more than five years, my heart is saddened by this loss – Kimura’s death at the age of 22 is just too early, too regretful. However, I somehow find disturbing the uniform responses of the Japanese public and the government, blindly calling for stricter regulation of online platforms and social networking services (hereafter SNS).

Death of a Terrace House Member and Domestic Reactions

With its first series launched in 2012, Terrace House has become one of the dramas that represent contemporary Japan. This reality show unfolds by following the ordinary lives of six residents – three men and three women from different backgrounds – who work, eat, sing, go out together, and sometimes fall in love with each other while living under the same roof. Terrace House has already documented five series of normal human interactions of residents who continuously enter, live for a duration, and leave. The show currently streams globally in more than 190 countries via Netflix.

Because of its expanding popularity, the death of a cast member of Japan’s representative TV series, which was confirmed on 23 May, 2020, soon sent shockwaves, both domestically and globally. While media outlets were quick to report on this incident, the public, particularly Terrace House fans, took to popular social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram to offer condolences to her and her family. Shortly after the confirmation of her death, Stardom, the professional wrestling organization that Kimura belonged to, also released an official statement on Twitter both in Japanese and English. Although the cause of her death was not immediately known, her recent SNS behaviors prior to her death soon contributed to an assumption that the Terrace House star had taken her own life. For instance, her last post on Instagram shows a photo of herself cuddling her cat with a message – “I love you, live a happy and long life. I am sorry.” On the same day when she was found dead in her apartment, Kimura posted on Twitter photos of her wrist and arms full of cuts. She is also reported to have suffered from mounting amounts of abusive online comments and messages, particularly following her clash with one of the male residents in an episode released in late March.

(Kimura Hana (Right), a professional wrestler and former member of Terrace House: Tokyo 2019-2020, who died at the age of 22/ Photo via Battle News)

Waves of public sorrow, anger, and condemnation ensued in the wake of the incident. Fans flocked to her Instagram account and left messages of condolence on her last post. The public responses appeared uniform, with the vast majority of them either rebuking anonymous abusive and heartless online comments or demanding tighter regulations of SNS platforms. In responding to the incident, the hashtag “hibo chusho” (name-calling/abuse in Japanese) was widely used, and over 1.3 million posts containing this keyword were uploaded in less than two days after Kimura’s death.

The outcry of the Japanese populace was joined by a consortium of celebrities, TV personalities, athletes, and even political figures expressing the same view towards Kimura’s death. For instance, Maezawa Yusaku, an entrepreneur and leading figure in the Japanese e-commerce industry, stated, “Excessive defamation should be severely punished.” Victims need not ignore the abuse, but to file a complaint. From the political sphere, former prime minister Hatoyama Yukio also tweeted a call for penalties for severe, targeted harassments that take place online.

Free Speech in Danger?

The death of a young, promising woman is truly a tragedy that evokes grief and anger, everyone agrees. But, would absentmindedly advocating SNS regulations soothe our troubled emotions? What I find disturbing is the blind public reactions to the incident and the political landscape that exploits the emotional nature of the issue to serve their interests. We must start thinking carefully about and taking seriously the ongoing discussion of SNS regulations – and of the broader issue of free speech – before it is too late.

In the wake of Kimura’s death, the Japanese government and politicians, which were lagging in planning and enforcing concrete and coherent measures against the COVID-19 epidemic, appeared quick and decisive in supporting – or exploiting – the public outcry. On 24 May, just one day after the Japanese wrestler was found dead, the Minister of Internal Affairs and Communication Sanae Takaichi told the media that she would speed up governmental discussions on proper measures to help identify anonymous internet and SNS users whose posts and comments included slander and defamation. On 25 May, the Japanese political sphere saw a rather rare confluence of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), both of which tend to hold discordant views about social, legal, and political issues. Diet affairs chief Moriyama Hiroshi from the LDP had a brief meeting with Azumi Jun from the CDP. During the meeting, Moriyama and Azumi articulated the need for political action to avert the recurrence of such tragedies. The meeting culminated in an agreement between the two oppositional political parties on accelerating an official dialogue regarding a set of anti-cyberbullying rules and regulations, on which they hope to reach an official consensus by fall.

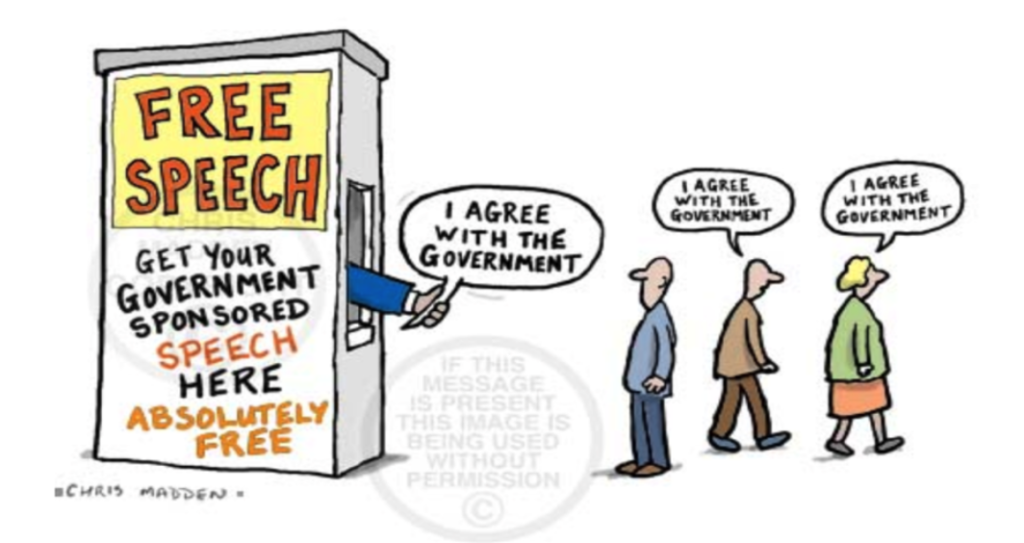

(Political satire criticizing governmental measures to curtail free speech/ Photo via Chris Madden)

At a glance, all of these appear to be natural political responses to the tragedy. However, what agitates me is the very speed at which the politics is moving. Kimura’s agency did not release any information regarding the cause of her death. Yet, politicians immediately condemned abusive online comments and prompted debates to regulate SNS platforms. Given her last Instagram post that could be translated as her last will and testament, we now know that her death is most definitely connected to malicious online posts and name-calling. Kimura’s death should raise awareness of cyberbullying and prompt discussions about how society should address that issue. It should not, however, provide a golden opportunity and rhetorical cover for politicians to restrict the free exchange of personal opinions and views criticizing their policies.

Principles of free speech guarantee the freedom and right of the individual and community to articulate and express their opinions and views without fear of interference, censorship, or sanction. Of course, we all know that the idea of free speech, in reality, is subject to numerous limitations. Imagine a murderer willingly and knowingly falsifying his/her statements under oath in court or someone publicly uttering words that clearly constitute virulent forms of coercion and intimidation against specific others. In many parts of Europe, there are laws in place that make it illegal to deny the Holocaust. Those cases are the ones in which we as a society would all agree on – or at least have a majority consensus on (e.g. Holocaust Denial) – placing legal and political restrictions or regulations on the idea of ‘speech.’

Once we move beyond the boundary of such crystal-clear cases, however, the demarcation of what exactly should and shouldn’t be, protected by the principle of free speech becomes extremely murky. And that is perhaps the biggest challenge for anyone who grapples with the idea of free speech; that is, we cannot really articulate beforehand reliable criteria on what can and cannot be said. Scholars and philosophers can spend most of their lives reading, learning, and debating the issue of hate speech. Yet, they never get to the bottom and arrive at any meaningful criteria of hate speech that anyone from any background can agree on. Regulating free speech is and should be extremely difficult, and perhaps that is why it is called ‘free’ speech.

In addition to the swift political responses, what adds fuel to my worry is the fact that politicians are simply calling for SNS regulations while leaving the crucial question of ‘how’ unaddressed. The political rhetoric that developed following the incident is something like ‘we will control and ensure a safe online and SNS environment lest users face malicious comments and posts to hurt them.’ How would the politicians taxonomically demarcate the line between free speech and verbal abuse though? Kimura’s Instagram did get flooded with heartless, inhumane comments dwelling upon her supposed lack of femininity, picking on the dark skin she inherited from her Indonesian father and even telling her to die. But, comments also included words of criticism of her outspokenness and personal views about her behaviors in the show. And these expressions of convictions, criticisms, or attitudes are the kinds of ‘speech’, that, if anything, the principle of free speech should cover. Some might also say anonymous online activities are recreant or hazardous, but anonymity is also an indispensable part of free speech that allows those who are not in power to express dissenting opinions without fear of retaliation and ostracism. Imagine a situation where you write an online editorial criticizing an outspoken politician whose political inclinations are too radical or antithetical to basic democratic values, let alone your own ideology. Your work gets scrutinized, censored, and deleted. Online anonymity is no longer a thing, and the next day you find yourself in jail for your unprotected verbal activities. Is this a society we aspire to?

Governments in many parts of the world have long suppressed lawful and peaceful civil activities that they see as unfit, including anti-government protests, critical journalism, and academic writing. The idea of free speech exists to safeguard citizens against these repressions. The dystopian society – at least to me – that I drew above is extremely unlikely, but not impossible. While we mourn for the sudden death of the young professional, we should ask ourselves one more time if the political debates surrounding one of our most fundamental rights should be proceeding at this dizzying speed – before it is too late.

Shugo Okaeda holds a BA from Monash University, Australia and is currently completing his MA at Korea University, South Korea. Previously, he worked as a research assistant at SSK Human Rights Forum and is currently working as a research assistant at Korea University. He has previously written for NOVAsia.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024