Kimchi. The ubiquitous spicy fermented cabbage dish that haunts our lives in Korea. Some people love it. Some people loathe it. But as long as you’re living in Korea, you can’t avoid it. And when the latest spat between China and Korea broke out in December 2020, you might be forgiven for thinking it was about North Korea. Or maybe THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Defense System) deployment. Or perhaps even fishing rights in the Yellow Sea. But no. It was, as I’m sure you will have guessed by now, about the humble side-dish, kimchi.

It all started back in November 2020 when the Swedish-based International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) updated their regulations for the making of pao cai. That’s a pickled vegetable dish, popular in China. The Global Times, China’s state sponsored tabloid pounced on it, claiming China was leading the way in setting an international standard for kimchi.

Pao Cai, a pickled dish popular in Sichuan, China. (Photo: by Yuan Report, Youtube)

Confusion arose because the word pao cai in Chinese not only refers to the Chinese dish, but also, confusingly, to kimchi. Pao Cai is one word for two different dishes. The fermented spicy Korean kimchi, and the pickled Chinese vegetable dish, pao cai. However, as the Korean Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs points out, the ISO document itself says, “this does not apply to kimchi.” The ruling only refers to pao cai, the Chinese dish.

A perceived attack on Korea’s national dish was bound to lead to a fiery response from netizens. Kim Seol Ha told Reuters: “I read a media story that China now says kimchi is theirs, and that they are making international standards for it. It’s absurd. I’m worried that they might steal hanbok and other cultural contents, not just kimchi.”

In an interview with Yonhap News Agency, Seo Kyoung Duk of Sungshin Women’s University said these actions by the state sponsored Global Times showed a concentrated attempt at cultural appropriation by Beijing. Cultural appropriation is the adoption of elements of one’s culture of identity by another culture. This can be controversial when a dominant culture appropriates from a minority culture. Seo Kyoung Duk went on to say, “cultural appropriation can happen when one group envies a tradition of another. With South Korean cultural content expanding its influence on a global scale, it seems that China is making efforts to claim that such content was traced to them.”

People have been eating kimchi on the Korean peninsula for at least 3,000 years (though the modern spicy variant did not become popular until the arrival of peppers in the 1600s). It’s important to understand that kimchi is not just a fermented side-dish for Koreans. It’s an inter-generational family bonding activity and an intangible cultural heritage. Every year, in late November, families get together and make a year’s worth of kimchi in the traditional way, known as kim jang. It involves the gathering of salt, spices and anchovies before fermenting the kimchi in large clay pots. According to UNESCO, kim jang “transcends class and regional differences…and reaffirms Korean identity.”

Various types of kimchi and other side dishes for sale at a market. (Photo: wikicommons)

I spoke with Lee Yoon Hyuk, who trained and worked as a chef in Korea and Japan. He told me, “with the Westernisation of food culture in Korea, people are eating less kimchi. And compared to the older generation, the average family size is much smaller. So people don’t really cook at home, and they make less kimchi than before.”

Kimchi is symbolic of the Korean identity. But research shows that kimchi consumption has dropped over the last decade, especially in urban areas such as Seoul and Busan. Factors such as rapid industrialisation and changing dietary patterns have been cited. Just a stroll through the streets of any Korean city would see a dozen Starbucks, KFC’s, Subways and McDonald’s. But, in rural areas, without so many Western-chains, kimchi consumption remains high.

While Mr. Lee’s family do practise kim jang, these days 40% of commercial kimchi is imported from China, and of the kimchi produced within Korea, 99% is made from napa cabbages imported from China. The mass importation of kimchi from China coupled with the erosion of kim jang poses a threat to kimchi as a symbol of Korean identity and culture. If that’s to carry on, changes in production and consumption are vital.

The price of napa cabbage has soared in recent months. (Photo: wikicommons)

These tensions come at a tough time for kimchi lovers worldwide. 2020 saw one of the longest rainy seasons in Korean history, with fierce typhoons devastating the year’s crops. The prices of napa cabbage have gone from around USD $2.50 to USD $14 per head. The price of radish and garlic have also increased due to the poor crop yields. Kimchi is often available as a free and refillable side dish at most Korean restaurants, but, with rising prices some places have stopped offering this service. For a country that insisted on sending kimchi to the moon, this is almost a national emergency.

This so-called “Kimchi War” isn’t the only recent soft-power conflict fermenting between China and Korea. The K-pop band BTS, with over 5 million followers on Weibo, came under fire for mentioning that the US and Korea shared “a history of pain,” referring to the Korean War that began in 1950. They gave these comments after receiving the Korean ‘Van Fleet’ award, commemorating US-Korean ties.

Predictably, The Global Times picked up on this comment, reporting that “the band’s totally one-sided attitude to the Korean War hurts their [Chinese fans’] feelings and negates history.” Shortly after those comments, adverts featuring BTS were pulled from the Chinese market. They aren’t the only ones, with girl group BLACKPINK coming under fire that same month for panda-handling related controversies.

BLACKPINK also faced criticism for their handling of a panda cub. (Photo: Twitter)

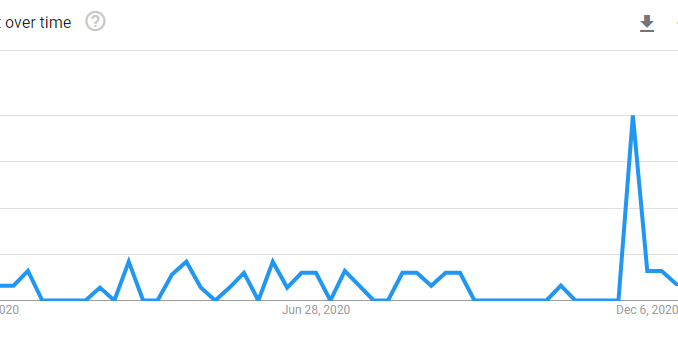

The Chinese netizens’ offensive against ARMY (the name given to fans of BTS) didn’t last long. BTS never responded publicly to the ‘controversy’ and two days later, the Global Times deleted many of their anti-BTS articles. For BLACKPINK, BTS and many K-pop bands, this cycle of controversy seems to come and go with no lasting effects on their popularity or fan base. The same is true for the ‘Kimchi War’, with the last article referencing the conflict appearing in the Global Times dating back to December, and the original inflammatory article having been deleted.

Spiking after the ISO certification, searches for pao cai have recently flatlined, signifying the end of the controversy, for now. (Photo: Google Trends)

The two countries have a long list of real issues to resolve: from China’s support of North Korea, to the close proximity of US bases to the Chinese border. Perhaps it’s better that these tensions express themselves by squabbling over K-pop and kimchi rather than any other way.

But when two parties disagree on something, sometimes the best thing to do is talk over a meal. Good food makes for good diplomacy, and whether that’s served with a side of kimchi or pao cai, I don’t mind.

Daniel Engel did his Masters in dead languages but these days his interests are more modern. In order to escape Welsh weather, he told his parents he was going to live in South Korea for a year. That was a decade ago. When he’s not writing an article or reading a book, he’s trying to untangle the mysteries of Korean grammar. He has written for NOVAsia before.

Daniel Engel did his Masters in dead languages but these days his interests are more modern. In order to escape Welsh weather, he told his parents he was going to live in South Korea for a year. That was a decade ago. When he’s not writing an article or reading a book, he’s trying to untangle the mysteries of Korean grammar. He has written for NOVAsia before.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024