Introduction To Japan’s Relationship with Nuclear Radiation

Across history, Japan remains a tragically unique case as the only country to fully experience the actual cost of nuclear power in each aspect of its relationship with radiation. This unparalleled history is filled with enduring the effects of atomic weaponry by The United States’ bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the impacts of The United States’ nuclear development testing in Bikini Atoll, and one of the worst nuclear power plant meltdowns in the history of the world at its Fukushima reactor. Throughout this relationship with radiation, the country has suffered significant losses in human life, quality of life, and degraded soil and water, which has forced the country to confront a reality filled with death, destruction, and loss encompassing hundreds of thousands of lives.

Rooted in these historical events spanning the country’s history from 75 years ago to as recent as 11 years ago, the Japanese people’s and government’s relationship with nuclear radiation has directly impacted the socio-cultural and political landscape of the country in the last century. Whether it is in the form of nuclear fallout, radiated areas, or radioactive waste, as the nuclearization of countries continues to grow, the international community must understand and recognize the effect it has had on countries such as Japan through its relationship with radiation.

The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

In modern times, the conversations relating to atomic weaponry and nuclear capabilities have dominated international relations. By garnering a notorious presence as one of the leading aspects for global consideration, smaller nations have started to view acquiring a nuclear arsenal as their ticket to the world stage, while bigger nations build up their nuclear arsenals in the form of military posturing to boost their position of power. These approaches to developing power structures view nukes as a balancing force that requires the world’s major powers to respect their place at the international table or one that expresses and projects their higher position on the global hierarchy ladder. Nevertheless, outside these political maneuvering and military advantages of growing their arsenals and reaching production capabilities, their true human cost is only fully realized once used in military conflict.

Four months into his surprise presidency after the death of The United States President Roosevelt, President Truman’s strong desire to end World War II combined with the newly developed atomic bomb from the Manhattan Project, situated The United States as the first and only government to resort to utilizing atomic weaponry in military conflict. On August 6th and August 9th, 1945, the world’s first nuclear bombings on a country killed an estimated 210,000 people in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. With a casualty rate of more than 90% civilian, the incomprehensible majority of these victims were everyday people that had their skin melted, exposing their muscles and bones, crushed by the force of the blast in their own homes, and extreme radiation to the point of bloody vomiting and clasping dead.

This direct use of atomic weaponry enacted an extraordinarily high and gruesome cost of human life that consisted of a large number of non-combatants, women, and children. While the justification for this horrendous act and the “actual number” of “direct deaths” has been debated, this form of casualties of the bombings is widely understood and recognized. However, the true human cost only continues to rise beyond the 210,000 initially killed, reaching far out into the destruction of life and normalcy for hundreds of thousands of survivors and the Japanese people.

Hibakusha 被爆者: “The Bomb-Affected People.”

Amongst the estimated 210,000 initially dead, current estimates believe there to be around 650,000 survivors who experienced medical life-altering or life-threatening effects from these bombings. While suffering terrible immediate injuries, most also continue to suffer life-long medical issues and continued development of illnesses such as various forms of radiation-induced cancers. If these medical injuries were not enough, heavy stigmas and discrimination were not uncommon for these survivors. Many survivors faced moments when they were treated as outcasts and even refused employment because they were mischaracterized as contagious, which can still linger in today’s society despite contrary medical information. It was not until twelve years after the bombings, in 1957, that an official term was given to the survivors of these bombings through the Atomic Bomb Survivors Medical Care Law.

Known as 被爆者- Hibakusha (The Bomb-affected People), this title serves as an official political classification under the original definition that outlines the classification of the “direct” survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This directness was initially defined as being either a few kilometers from the hypocenters of the bombs or within 2km of the hypocenters within two weeks of the bombings. Survivors who met this requirement from the government were given more substantial health benefits and governmental support. However, this initial definition of “direct” survivors of the bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki does not fully encompass the more extensive variety of atomic bombs and associated radiation-affected survivors.

In more recent and current times, additional revisions and additions of different forms of survivors have been made. As these changes are made, more survivors are gaining the classification of Hibakusha and the medical benefits that come with it. However, a prominent proponent of these changes in governmental recognition and types of benefits given to these survivors have had to fight for them through lawsuits and class action suits supported by significant public movements in Japanese society. With this growing revitalized discourse pertaining to radiation victims from these atomic bombings outside of the initially defined distance and time frame requirements, Black Rain survivors, survivors on the Daigo Fukuryū Maru fishing boat, and survivors of the Fukushima reactor meltdown are becoming more prominent figures in the larger discourse on radiation in Japan and the Hibakusha classification.

Black Rain Survivors

When Hiroshima and Nagasaki were atomically bombed, a mixture of nuclear fallout from the explosions, carbon residue from citywide fires, and harmful chemicals and remains of buildings were launched into the air, mixing with the water vapor and producing “black rain.” This dark, contaminated, and radioactive perspiration landed on people, houses, and contaminated food and water. Because of the interactions with the black rain, there were cases of widespread radiation poisoning not exclusive to the 2km radius regarded in the Hibakusha classification. Under the original requirements, these black rain victims did not qualify for the Hibakusha classification or the medical support that came with it. It was not until under public pressure in 1976 that the government first recognized black rain contamination victims, allowing them to receive the Hibakusha classification and medical support.

While many were able to be added to this classification, the government divided Japan into “heavy rain” and “light rain” zones based on the perceived amount of black rain observed in those areas. With this distinction made, only individuals in the “heavy rain zones” could receive medical benefits from the hibakusha classification. However, through continued public movements and a series of court cases and lawsuits, before the 75th anniversary of the bombings in 2020, the Hiroshima District Court recognized dozens more who lived in light rain areas. Most recently, this number was expanded to another 84 individuals in July 2021 through the Hiroshima High Court. This inclusion of Black Rain Survivors under the Hibakusha title highlights an essential aspect of Japan’s relationship with radiation. Including Black Rain Survivors shows that it is not only a singular interaction with radiation but one that also produced expansive fallout and residual radiation in other forms that affect the Japanese people, land, and water.

第五福龍丸 – Daigo Fukuryū Maru, The “Lucky Dragon Incident.”

After the initial bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and before the political classification of Hibakusha was officially created, another critical moment in Japan’s relationship with radiation took place. In 1954, Japan once again found itself on the receiving end of The United States’ nuclear development programs. However, this time, it was not through a direct bombing of the country but instead through the wide-reaching effects of The United States’ nuclear testing.

Daigo Fukuryū Maru (第五福龍丸) was a Japanese tuna fishing boat with a crew of 23 men who were contaminated by nuclear fallout from America’s Castle Bravo thermonuclear testing at Bikini Atoll, a coral reef in the Marshall Islands. This testing is more widely known as The United States’ testing of the hydrogen bomb. The crew of the tuna fishing boat were diagnosed with acute radiation syndrome and later developed acute panmyelosis, destroying the bone marrow’s ability to generate blood. This interaction, yet again with nuclear radiation, would re-instill fear and contribute to a growing perception that the United States only cared about their atomic-based research while caring very little for the treatment of the Japanese people.

This anti-nuclear and anti-American sentiment was not new in the period shortly after the bombings. However, the negative sentiment was considerably amplified and directed towards the United States and the Japanese government. The arguably fear-fueled movements towards the Japanese government were based on a predominantly perceived poor communication practice, inaction concerning its responses towards The United States, and subpar handling of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru and its crew’s contamination. There was a growing perception that there was a prioritization of research pushed by the United States government, with little recognition or sensitivity of the human cost, and the society wanted the Japanese government to do more.

The movements and public pressures formed by the general public helped push the Japanese government’s actions and have been accredited by many for the government’s more active and responsive actions shortly after. Most notably, this public pressure was seen in the form of the public-supported ban-the-bomb movement and arguably the public’s influence on establishing the earlier mentioned political classification of Hibakusha and their government-sponsored medical benefits. The inclusion of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru in the conversation on Japan’s relationship with radiation is essential not only because of the victims but also for its shift in the public’s mindset and involvement moving forward. No longer was the relationship with radiation only linked to the original bombings. The conversation and understanding expanded past a singular event and the events it caused, realizing that anyone could die or become extremely sick without even coming into contact with the “original bombs.” This realization informed and created a new understanding of the larger reality of Japan’s relationship with radiation, as one primed to continue and was continuing outside of the initial bombings.

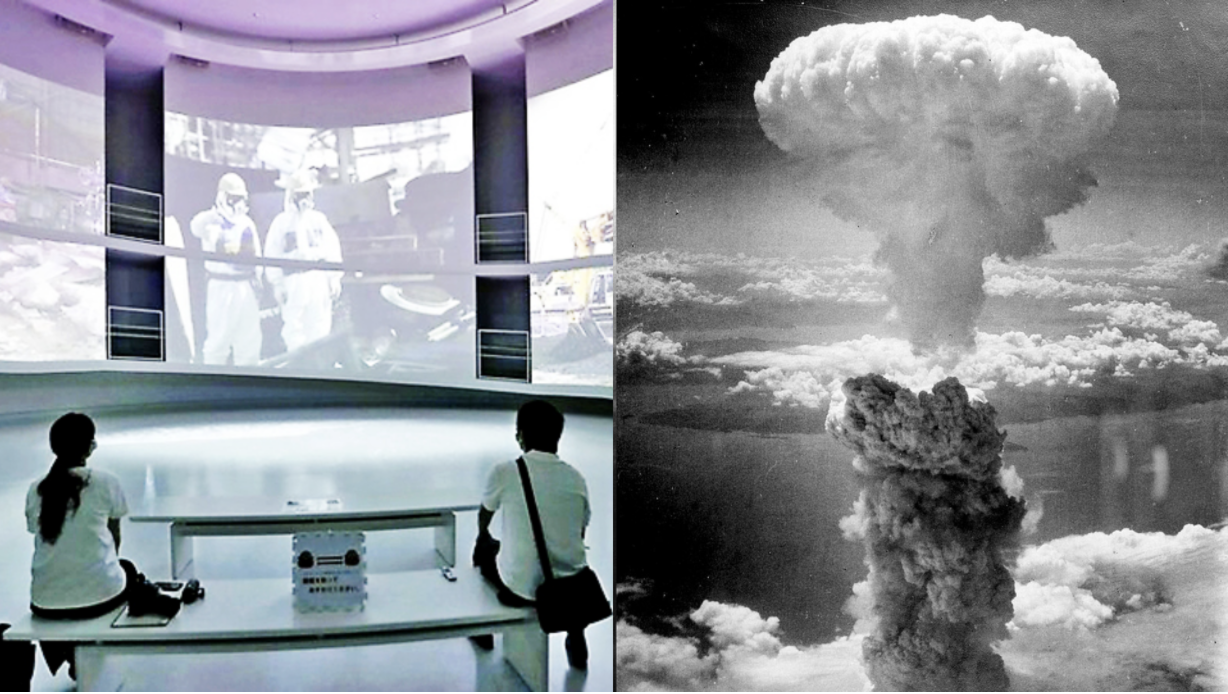

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

While cases of atomic weaponry can dominate the media when talking about radiation, it is not limited to only instances of military weaponry. While remaining relatively safe, nuclear power plants still produce radioactive waste that needs to be stored. In the case of a nuclear meltdown of a reactor, the radioactive fallout it produces can be catastrophic for the surrounding areas. So, on March 11th, 2011, when Japan experienced the fourth-strongest earthquake in the history of the world, followed by a massive tsunami wave off the coast near its Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, it triggered one of the worst nuclear meltdowns in history. Experiencing three reactor meltdowns, three hydrogen explosions, and a massive release of radioactive material, it is the only other event to receive the level 7 classification by the international nuclear event scale since the nuclear meltdown of Chernobyl.

The nuclear meltdowns contaminated large portions of the country and the Pacific Ocean by releasing multiple radioactive isotopes. Within 40 kilometers around the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant, 120,000 people were forcibly displaced from their homes due to high radiation levels. Now, ten years after the initial incident, these reactors still have possible leakage issues and require efforts to keep them cool. While large areas of Fukushima have been declared “habitable” by the Japanese government, most of the original population is highly hesitant and unenthused to return, based on a valid concern for the effects of the remaining radiation in the area.

The severe and long-lasting effects on the surrounding areas caused by the radiation from the reactors have created a societal and organizational inclusion of the population affected under the Hibakusha name. Many Japanese people, NGOs, and anti-nuclear movements have included the Fukushima reactor victims as Hibakusha, substituting bomb with exposure. With large portions of the population suffering from physical and mental trauma, delayed medical treatment, forced displacement, and some with radioactive-related illnesses from initial proximity or early return to the affected areas, this inclusion of non-bomb-related victims expands the understanding of what a radiation-related survivor is. While the government does not politically recognize these victims as Hibakusha or give them the same medical aid/benefits, many have received other forms of financial reparations from the government and the plant operating company TEPCO.

Relationship & Progression: Modern-day Into The Future

As of March 2021, 127,755 government recognized Hibakusha receiving medical benefits remain alive in Japan. In recent times, Hiroshima and Nagasaki have since rebuilt back into large urban centers, with Hiroshima being the largest city in the Chūgoku region of western Honshu. In the Tohoku region, ten years after the initial earthquake and tsunami, many areas in the region have undergone substantial reconstruction efforts and regained a sense of normalcy. However, that is not to say they are now disconnected from their relationship with radiation. Many areas in Fukushima remain inhabitable, and many towns deemed “safe” are still ghost towns. While Hiroshima and Nagasaki are major urban centers full of people, amongst these buildings are monuments and memorials dedicated to the survivors and the lasting effects of these bombings. As time has passed, forms of healing and rebuilding have taken place, but the relationship with radiation has not disappeared but merely progressed.

Many people suffered and died because of the horrific events and their corresponding radiation. With each new event, new forms of victims and survivors were created and often required legal battles and public movements to gain aid and recognition of their suffering. The continued and expanding discourse amongst the people and movements for these victims highlighted what it means to have a relationship with radiation. Survivors have lent their voices and experiences to advocate for denuclearization, non-proliferation, and general protection of peace in hopes of preventing a similar event from transpiring again. These testimonies now stand as a symbol and reminder for not only peace and non-proliferation but as a continued call to action to prevent similar tragedies.

Whether it is in the form of nuclear fallout from atomic bombings, radiated areas from nuclear testing, or nuclear meltdowns from power plant failures, radiation has induced immeasurable costs for human lives. From large death counts and multiple forms of survivors with life-long injuries, to the destruction of any sense of normality for people through displacements and contaminations of the land and water, the term Hibakusha truly encompasses what Japan’s relationship with radiation really is. As the nuclearization of the world continues, Japan has shown us that this relationship with radiation is defined by its victims, survivors, and its true human cost.