On March 31st, 2021 a young man was tied up naked inside a bathroom located in Yeonnam-dong, one of Seoul’s trendiest neighborhoods. 2 months and 13 days later police found him dead. The victim of this ‘Mapo Incarceration Murder’ was only 21 years old and weighed no more than 34 kilograms (about 75 pounds) by the time he was discovered. Police suspect his death was caused by two high school friends whose mistreatment resulted in starvation and pneumonia.

During those same two months, this trendy neighborhood hosted numerous young couples, university students, and office workers out for a night on the town. The area’s many CCTV (closed-circuit television) cameras and crowded sidewalks promised safety, so much so that a visitor to the area could have easily left valuables unattended with no fear of theft.

How can these two worlds coexist?

The fact that a young man can slowly die at the hands of “friends” in the same district where individuals safely enjoy a night surrounded by strangers seems like some bizarre paradox—almost as if the universe has created an incorrect reality. However, the coexistence of public safety and hidden crime seems a normal part of South Korean life.

The two suspects in the ‘Mapo Incarceration Murder,’ described above. (Image: Yonhap)

The presence of such hidden crime seems surprising given Korea’s favorable record. The nation ranks among the safest OECD countries and crime feels far from the neon lights that guard Seoul’s landscape. Credit cards left forgotten in public areas remain untouched by passersby, entering a crowd rarely results in stolen wallets, and someone walking home late at night likely won’t run into anyone more dangerous than an annoying drunkard. The country’s image of safety is further complemented by its lack of slums, dirty transportation hubs, a visible homeless population, or other indicators of crime. Korea’s soft power also plays a role as its most attractive qualities (which highlight well-behaved celebrities and wholesome drama characters) have become overseas phenomenons. From a glance, Korea simply exudes safety.

And yet…

While safe from public misdemeanors, less visible offenses are no strangers to the Korean news cycle. Fraud, bribery, domestic abuse, and reports of sexual violence often make headlines, and statistics show such crimes have increased in frequency. According to the Supreme Prosecutor’s Office sexual violence increased 51.6% between 2010 and 2020. Most of these crimes were conducted in the digital realm through the use of molka, or cameras secretly installed in motel rooms, bathrooms, or other private places to monitor the occupants. Korea is also plagued by corruption from both political and corporate leaders, and instances of fraud have increased 48.4% since 2010. However, Korea’s overall crime volume does not mirror these statistics, and even shows a 10% decrease over the last decade. Instead, crime has shifted forms. As the infractions listed above increased, others, such as theft, decreased 31.8%.

Why would theft decrease while fraud, sex crimes, and corruption persisted? The answer might lie in another characteristic of Korea, one often cited to explain the nation’s high suicide rate, developed beauty industry, and intense academic culture—the importance of appearance.

Perhaps it’s obvious that visible crimes like theft would wane in the wake of the global increase in public surveillance. While the first cameras meant for crime prevention were installed in the ritzy Gangnam district in 2002, Korea’s total CCTV use had grown to an incredible 1.03 million by 2019. The chance of crime occurring where so many digital eyes keep watch is slim. However, Korea has a unique reputation for correlating a pleasing outward appearance (be that in beauty, academics, career, or other surface-level details) with excellence, success, or merit. Many writers have noted this focus on appearance distracts from, and even exacerbates, other issues such as mental health, contributing to Korea’s place as the leader in suicides among OECD countries.

Perhaps it’s worth considering whether the nation’s bizarre crime makeup extends from this same esteem for appearance, encouraging prevention efforts in the public realm and neglecting those in the private. This emphasis on creating a society that looks and feels secure might produce safe public spaces, but it allows hidden crime to fall through the cracks.

A scene from Yeonnam-dong, a trendy area in Seoul. (Photo taken by the author.)

If Korea’s interest in appearance extends to the realm of law, then the country’s crime paradox begins to make sense. The feeling of safety then becomes tied to the impression everyone is doing what they ought to be doing. Are people fighting in the streets? Are there gang sightings? Has someone run away with a stranger’s purse? The lack of such behavior strengthens the impression of safety, and the easiest way to establish this environment is through strict public monitoring on the part of both individuals and authorities.

Monitoring civilians for the sake of public order has a long history in Korea. It hasn’t been many years since the country emerged from authoritarian rule, and even ex-president Park Geun Hye reimplemented controlling measures until she was impeached in 2016. Even now, monitoring still seems the preferred way to maintain the status quo. Most Koreans view the use of CCTV for crime prevention positively, and the tracking measures implemented to hinder COVID-19’s spread, though not without safety concerns, were accepted domestically with little opposition. This desire to monitor others’ conduct exists in other areas of life as well. At the popular level, K-pop artists and celebrities who deviate from the boundaries of their idol persona can face harsh criticism from fans, or even find themselves kicked out of their companies. On the political end, Korean professors often hesitate to introduce academic arguments against the accepted societal narrative as students have been known to petition against them. The fear of upsetting watchful eyes even travels to the private realm, where young people who live in small rooms with thin walls (called goshiwons), feel the need to suppress even normal bodily functions so as not to bother those in nearby rooms.

Within a society that puts such importance on social order, some crimes fail to survive, but others flourish. As CCTV cameras continue to increase, and civilians concerned with public conduct gather evidence of infractions, theft and other public breaches become harder to carry out. However, corruption and fraud are far more difficult to detect. Criminals can execute them under the guise of decorum by, for example, adopting trustworthy personas to extort money or bringing padded checks to a business partner’s wedding. The rise of digital sexual violence also shows a preference for unobtrusive crimes, ones that allow criminals’ own and society’s integrity to remain intact. Such a change in the makeup of crime polishes the surface of Korea while deviance moves into the shadows.

What’s more, hidden crimes are perpetrated by those who seek to uphold the law because they seem to pose a lesser threat to public order. For example, the country went into collective mourning at the beginning of 2021 when a toddler by the name of Jeong-in died at the hands of her adopted parents, but this was after three reports of possible child abuse failed to result in a police investigation. Multiple reports also criticize the lax response from police regarding cases of digital sexual violence, which often conclude in little more than a slap on the hand and victim shaming.

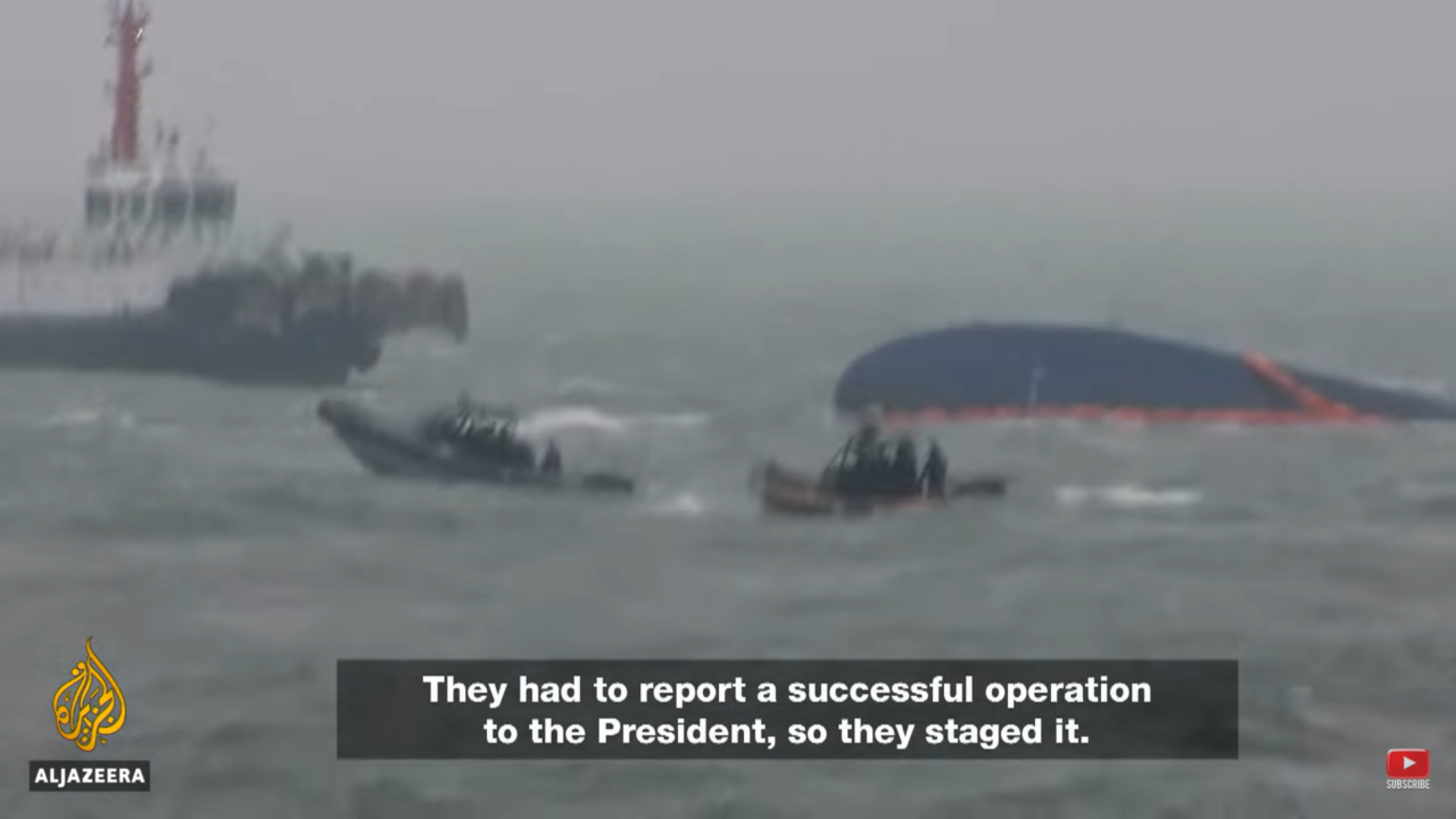

These incidents suggest the law takes reports of hidden crime less seriously than public violations. Sometimes, authority figures even favor appearance to the detriment of victims. For example, the 2014 Sewol Ferry Disaster in which 304 people died after their boat capsized during a high school field trip, could have easily been avoided if not for multiple layers of corruption and neglect. Yet even the attempt to rescue students was frustrated by personnel who cared more about putting on a show for the President than rescuing the children trapped inside the sinking ferry.

A screenshot from the documentary “In the Absence: South Korea’s Sewol Ferry Disaster | Witness.”

The above examples show criminals and the surveillance used to catch them often have the same goal—make what’s desirable more conspicuous than the deviant. In a society that elevates social decorum, authorities and criminals both feel infractions performed in secret less harmful—if it doesn’t reflect poorly on me or society, then no reason to worry, right? But looking clean does not stop crime from occurring, and carrying out crimes in private do not make them less damaging.

Crime has no easy solution. As for increased monitoring, it carries concerns of its own and can only force deviance deeper underground. Instead, and with the risk of making another large claim in an essay full of large claims, perhaps society needs to focus less on managing the appearance of deviance and come to terms with why crimes occur in the first place. A high regard for social protocol will cause us to lose focus on what’s really important—valuing the lives of others. Until concern for others overshadows to need to appear successful, competent, or even safe, the battle with hidden crime will continue.

- Behind Closed Doors: The Paradox of Korea’s Hidden and Public Crimes - August 12, 2021

- The Peninsula’s No.1 Korean Wishes to Tell You, “Don’t be Lonely” - May 27, 2021

- Korean Literature: The Black Sheep of Hallyu - April 8, 2021