People often ask me why I moved from my home country of Australia to Seoul. My answer is always the same: I didn’t move to R.O.K. because of what I knew about the place. In fact, I moved here because I knew next to nothing and I wanted to try something new. However, even in the past couple of years, R.O.K. has become a country that is increasingly on the radar of Australians through their cultural attractions whether that be music, film, fashion, or food.

Through my studies at Yonsei, I have since learned a great deal about Australia and R.O.K, especially within the realm of international security. The two countries share similar values – both are democratic countries and both have deep ties with the U.S. A little known fact for many is that almost 100,000 Koreans live in Australia and in the year prior to COVID-19 (2018-19) more than 280,000 Koreans chose Australia as their holiday destination. Theoretically, there is plenty of fertile ground for Australia and R.O.K. to deepen their security ties – and yet it may not be that simple.

Australian Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese (left), with US President Joe Biden (centre), and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Source: Leon Neal/Getty Images.

Recently, Australia announced the AUKUS Security Agreement, which is a trilateral agreement between Australia, the United States, and United Kingdom. A major component of the agreement is that the U.S. will help Australia develop five nuclear-powered submarines by 2055. This agreement means that Australia is effectively signalling to the world their close alliance to the U.S. and U.K.

But is Australia emphasising their alliance with the U.S. and U.K. at the expense of their Asian neighbours? Regardless of how powerful the United States are, the question must be asked – should Australia be joining themselves at the hip with countries on the other side of the world? In this article, I’d like to explore an alternative route by considering how Australia can improve its security through deepening its ties with Asian countries and in particular, with the Republic of Korea (R.O.K).

Australia-R.O.K: As Things Stand

As already mentioned, the R.O.K. and Australia are not two countries often paired together, yet they share significant common interests and values that are worth acknowledging. In fact, during the Korean War more than 18,000 Australians fought to defend South Korea. In modern times, both countries hold significant influence in the Indo-Pacific region through trade and commerce. The R.O.K. is Australia’s fourth largest trading partner and investment between the countries is increasing with R.O.K. exporting electronics and machinery while Australia exports energy, raw materials, and food products.

Within the Indo-Pacific, Australia and R.O.K. can be considered as two Middle Power’s seeking to navigate their way through a rapidly changing geopolitical environment. This context means that expanding Australia-R.O.K. relations beyond economics and commerce and into the realm of strategic security alignment presents an array of opportunities. In 2021, then R.O.K. President Moon Jae-in and former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced plans for a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ between the two countries. Within this initiative were the usual key issues of trade and investment however defence and arms development were also listed as key areas for development. A $680 million deal was signed which would see R.O.K. provide Australia with artillery weapons, supply vehicles, and radars.

It is reasonable to assume that part of the reason for this initiative was because of a mutual concern surrounding China. In recent years, both countries have been subject to economic hardship at the hands of China. In the case of R.O.K., Beijing enforced economic sanctions in 2016 after R.O.K. announced plans to develop Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) technology with the United States. Australia, whose economy has been heavily reliant upon investment from China, also experienced a severing of economic ties from China that began when they banned Chinese 5G technology in 2018 from being installed within their borders. This background partially explains why Australia and R.O.K. have increased economic ties, diversifying their economy away from a reliance upon China. However, in terms of security, a shared concern about an increasingly looming China may not necessarily be the case.

Australia-R.O.K: Hurdles That Need To Be Overcome

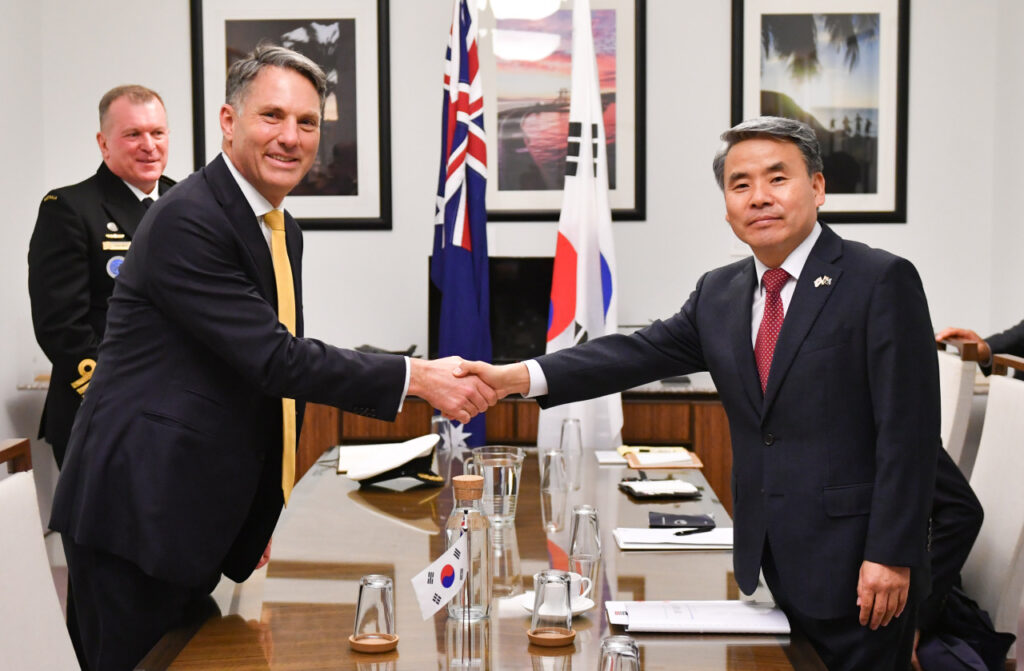

Australian Defence Minister, Richard Marles, shakes hands with R.O.K. Defensive Minister, Lee Jong-sup. Source: Ministry of National Defense.

Last year, South Korea’s Defence Minister Lee Jong-sup met with Australia’s Defence Minister, Richard Marles. According to a report from the Australian-based think tank, Asialink, the agenda included discussing defence links and cooperation as well as regional security. Among these objectives, Mr. Lee sought to discuss the proposition of R.O.K. providing defence materials such as fighting vehicles and submarines. Beyond the practicality of this meeting, it would appear that there are a raft of common strategic interests on the surface, beginning with how both countries consider the U.S. as a key ally.

However, an important difference exists between how the two countries perceive China. Australia sees China as a threat, and seeks to act as a backstop for the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific while the R.O.K’s stance is much more complex and ever-changing. This is because from the perspective of Seoul, there is the challenge of balancing both Washington and Beijing. In a 2021 meeting between former R.O.K. President Moon and U.S. President Joe Biden, plans to deepen bilateral cooperation were announced, with their alliance expanding to include regional and global impact. However, President Moon has since left office and been replaced by President Yoon Suk-yeol. Last year, President Yoon was interviewed on CNN and pressed about what ROK would do if China lashed out and there were a crisis in the Taiwan Strait. Would Korea jump to the side of the U.S.? Interestingly, President Yoon insisted that while Korea supported liberal values, their priority was to defend the Korean Peninsula.

Australia-R.O.K: Looking Beyond China

Because there is a crucial difference between Australia and R.O.K’s perception of China, it’s therefore important to look beyond this thorny issue and to foster broader relations. For every Australian, maintaining peace in the region of the Indo-Pacific is essential. Despite this, it is undeniable that North-east Asia is a region experiencing rapidly increasing tensions. North Korea continues testing ballistic missiles, going as far as to launch missiles off the coast of R.O.K. and Japan. Meanwhile, to the west, Russia is at war with Ukraine, while China continues to flex its muscle. Baring this context in mind, shifting R.O.K.’s interests to look beyond the Korean Peninsula is likely a fruitless endeavour.

The situation in North-east Asia is complex and is, no doubt, a factor behind Australia signing the AUKUS Agreement with the United States and United Kingdom. For many Australians, there can be an assumption that R.O.K. is a country with deep historical ties with the U.S. and that this means they largely follow in lock step with the security priorities of the U.S., just as Australia does. However, this is not the full picture. Understanding R.O.K’s security concerns is crucial for Australia to broaden their relations not just with R.O.K. but also with other Asian countries.

It’s important to know that more than a quarter of Australians were born overseas, and almost half of Australians have a parent who was born overseas. Many of these families hail from Asian countries. Because of this, there is an enormous appetite among Australians to deepen ties with countries such as R.O.K. My concern is that as a result of the AUKUS Agreement, Australia will remain deeply intertwined with the United States and the United Kingdom moving forward for decades to come, at the expense of their Asian neighbours. Moving forward, Australia would do well to acknowledge their connection with their Asian neighbours, expanding our network of allies in the region, with the Republic of Korea being at the forefront.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024