Most of us around the world are well into our state-sanctioned, mandatory month of social isolation. While living our best shut-in, internet-immersed lives, we don’t have to spend too long online to find something new to alleviate our boredom, from creative challenges to breadmaking videos, to Animal Crossing character updates. With our rapidly growing time spent on the internet, it is easy to fall into the trap of clickbait and buzzword articles, easy to take things at face value.

The turn of the news cycle is faster than ever – yesterday’s tragedy is today’s forgotten memory, and likewise, it has become impossible to ignore the sheer volume of worldwide media coverage surrounding Covid-19 (a quick plug of the word ‘coronavirus’ into Google yields over 2 billion search results). But, we are so caught up in our current situation and its implications on the future that we have seemingly forgotten how this all started, and what came before it.

For one, the Australian bushfires which were the trendiest Instagram stories only days before the outbreak of Coronavirus have been all but forgotten. Despite the devastating physical effects of an event as big as the 2019-2020 bushfire season, attention on its major and lasting consequences have been erased by a virus we cannot see. Our generation’s short attention span is an accepted reality, but the speed with which we move on from tragedies shows a paradox in how we use social media to deliver response, spread awareness, and call for action.

Bushfires are something commonplace in Australian summers, an expected danger in the Outback. Perhaps this is why the ferocity and enormous scale of last year’s season was initially dismissed by international news coverage and social media even as dirt coloured rain and hazy ash enveloped urban cities. From September 2019, fires heavily impacted several regions in South Eastern Australia (the regions with Sydney and Melbourne) before spreading across all Australian states and territories. The fires peaked between December 2019 and January 2020, when air quality dropped to hazardous and toxic levels, and smoke was so thick that it blew 12,000 kilometres across the South Pacific Ocean to Chile and Argentina. To date, 18.626 million hectares of land around the country has burnt (for context, that’s bigger than the total land area of South Korea, which reaches just over 10 million hectares), and it is estimated that more than a billion animals have died.

(18.6 million hectares overlaid across South Korea and Europe/Captured from The Guardian’s interactive map)

Attention on the issue was slow to spark, with social media and international news outlets only beginning to take notice of the crisis in the first week of January (four months after the start of the fire season), and after a massive 5 million acres of land had already gone up in smoke. Instagram and Twitter flooded with pictures of burnt kangaroos and exhausted koalas, with celebrities like Chris Hemsworth, Kylie Jenner, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Russell Crowe capitalising on their star power to urge followers to donate.

Why does it take sad pictures of animals to tug at our heartstrings before we spur into action? Where was the global political outcry and international media coverage for Australia before this?

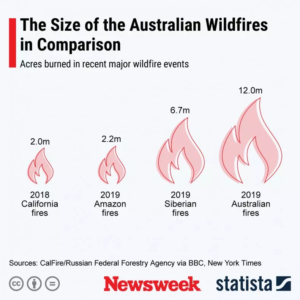

To compare, the 2018 Californian Wildfires, which claimed about 800,000 hectares, are said to be the most deadly and destructive in California to date. The likes of the Kardashian family and Guillermo del Toro immediately took to social media asking for thoughts and prayers. The Amazon fires of 2019, which dominated social media with the hashtag trend #PrayForAmazonia saw 900,000 hectares burnt. Europe’s richest man alone, Bernard Arnault of LVMH donated $11 million to the cause. And, the 2019 Notre-Dame de Paris fire which undoubtedly caused the quickest and most outrageous media response was pledged €1 billion of reconstruction funds in less than a day.

(Comparison between wildfires/Source by Newsweek)

Meanwhile, an estimated A $500 million has been publicly donated for the Australian bushfire’s victim relief and wildlife recovery. While this is no small sum, the relative amount to the scale of the natural disaster seems underwhelming when measured against donations for Notre-Dame. The delayed responses to the Australian bushfires allowed the toxic smoke to cross the Pacific Ocean and to date has emitted approximately 900 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (nearly double of Australia’s total yearly fossil fuel emissions). It is predicted that this sudden and sharp increase in carbon concentrations will hasten the effects of global warming. An estimated 70% of the koala population has also been wiped out, and the ecosystems of thousands of other native animals, insects, birds, and plants irreversibly disrupted.

Through it all, the Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison tried to cover up holidaying with his family in Hawaii, hosted a New Years Eve party at his home despite the sombre situation, and the government continues to deny that climate change had anything to do with the unusual, scorching temperatures of the summer. Perhaps our apathy on the issue springs from the lack of our leader’s political will. If politicians and news outlets can offer delayed and half-hearted responses, then why should we be expected to continue caring?

(Memes abound, criticising ScoMo’s lack of political action/Picture by Getty Images via The Canberra Times)

Just two months on, the urgency of the Australian bushfires are largely forgotten (although they are technically still ongoing), as the country and the world chokes on the rapidly spreading Coronavirus pandemic – Aussies themselves are more interested in cataloguing viral videos of toilet paper panic buying, and old ladies fighting at the supermarket. Perhaps it’s unfair to compare the scale of a single country’s bushfire to a global pandemic, but both are causes for international concern, especially considering the implications and carry-on effects of a climate disaster.

Ironically though, the running theme of many viral Tweets at the moment revolve around the idea that animals and nature are flourishing in this crisis. Recently, Tweets about swans and fish returning to Venice and wild elephants getting drunk on corn wine due to the absence of humans went viral before National Geographic exposed both to be fake news. Despite knowing it was false information, the original posters refused to delete the Tweets, citing that the number of likes and retweets were unprecedented and a personal record for them, something they would like to keep.

Maybe we’re more inclined to cling onto positive messages (even if we know they are fake) because we want something good to believe in; that if we must suffer, then at least Mother Nature is all the better for it.

But these fake, happy news stories are irresponsible and problematic.

We should consider the privilege and power we hold as social media users and take accountability for the issues we raise awareness for. It seems like we are eager to move from one trendy news story onto the next, going up in arms about bat-eating in Wuhan, but forgetting that whole species have been burnt out. We threw money at organisations, pleading to save the koalas, but how many of us have actually followed up on where our donations are going or how the koalas are recovering? We’re only empathetic in the moment but a collective amnesia seems to occur once the moment has passed.

I am not claiming that we must conduct in-depth research on everything we share, or that we should remember every disaster that has ever befallen the human race. But if we are to put our money where our (social media) mouth is, we should be advocating the causes we post about for longer than a 24 hour Instagram story.

It may be true that Australia sits in the ‘opposite’ corner of the globe and is not within the same large spheres of cultural and political influence as the US, Europe or China. But more than ever, we should no longer remain passive to the things that don’t directly affect us. We should consider our access to social media and the Internet as privileges. This is something very powerful, and a tool that our ancestors did not have when trying to start revolutions, stop wars, and build societies. More than ever, we are capable of coming together to demand change and Coronavirus has especially shown we have the ability to transfer information at light speeds. As the world increasingly becomes interconnected, we have the shared responsibility to care for one another, even if we don’t consider something to be ‘our disaster’. As we consume more technology and the Internet during this time of social distancing, let’s take a moment to reflect on our social media habits – how we share news, what kind of information we share, why we share it and how we can do it better.

- Not Your Punchline or ‘Happy Ending’ – the Mediatization of Asian-American Identities and Hate Crimes - March 24, 2021

- I’m Asian Australian. Why should I care about Blak Australia or Black America? - June 5, 2020

- Does Anyone Remember What Happened to Australia?: The Illusion of Social Media Activism - April 21, 2020