With all of the attention surrounding the heavyweight bout between Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump that appears to be taking place in May, it is important not to treat the April summit between Kim and South Korean president Moon Jae-in as merely a warm-up leading up to the main event. The inter-Korean summit carries its own significance. While President Moon has been a reliable cosigner of America’s pressure tactics in the face of North Korean aggression throughout 2017, South Korea still pursues its own policy towards North Korea.

Part of this policy is South Korea’s short-term goals of increasing human and material exchanges with the North. Here, the scope for negotiations is wider. Meetings with South Korean officials and their North Korean counterparts have been constructive, resulting in cultural exchanges and an ebb in North Korean military activity.

Additionally, Seoul has shown its diplomatic dexterity in dealing with both Pyongyang and Washington. After the steady stream of sanctions and pressure while simultaneously pursuing talks with Pyongyang in the months leading up to the breakthrough in January, South Korea then facilitated the North’s Olympics participation, and was the first to be granted an audience by the reclusive Kim Jong Un. Indeed, no one has been able to get through to North Korea like South Korea. Kurt Campbell, a former Obama administration official for East Asian Affairs, said at a recent conference in Washington that, “South Korea has the ability to drive many of the dynamics…in Northeast Asia.”

We can see President Moon driving these dynamics through his proposal to have a trilateral summit between South Korea, North Korea, and the United States. Besides keeping South Korea on equal footing in negotiations, the Moon-Kim summit would also put Seoul in a position to support Washington. Many in the American foreign policy community are expressing concern over President Trump’s lack of foreign policy experience during his negotiations with Kim, which the American president accepted without any prior known communications with North Korean officials. Jung Pak, formerly of the CIA and now with the Brookings Institution, said she is worried that Kim will appeal to Trump’s America First agenda in an attempt to weaken US military alliances the United States itself in the region. It has been North Korea’s ultimate desire to separate the United States from the Korean Peninsula, and China’s effort to insert itself into the equation by inviting Kim Jong Un to Beijing for an unofficial state visit was certainly meant to tip the diplomatic scale towards Pyongyang.

Moreover, the US State Department is currently bereft of experienced North Korea experts; the administration’s top North Korea envoy recently retired, and Washington still does not have an ambassador in South Korea. With an administration void of experience dealing with North Koreans, the United States can learn a thing or two from their South Korean counterparts.

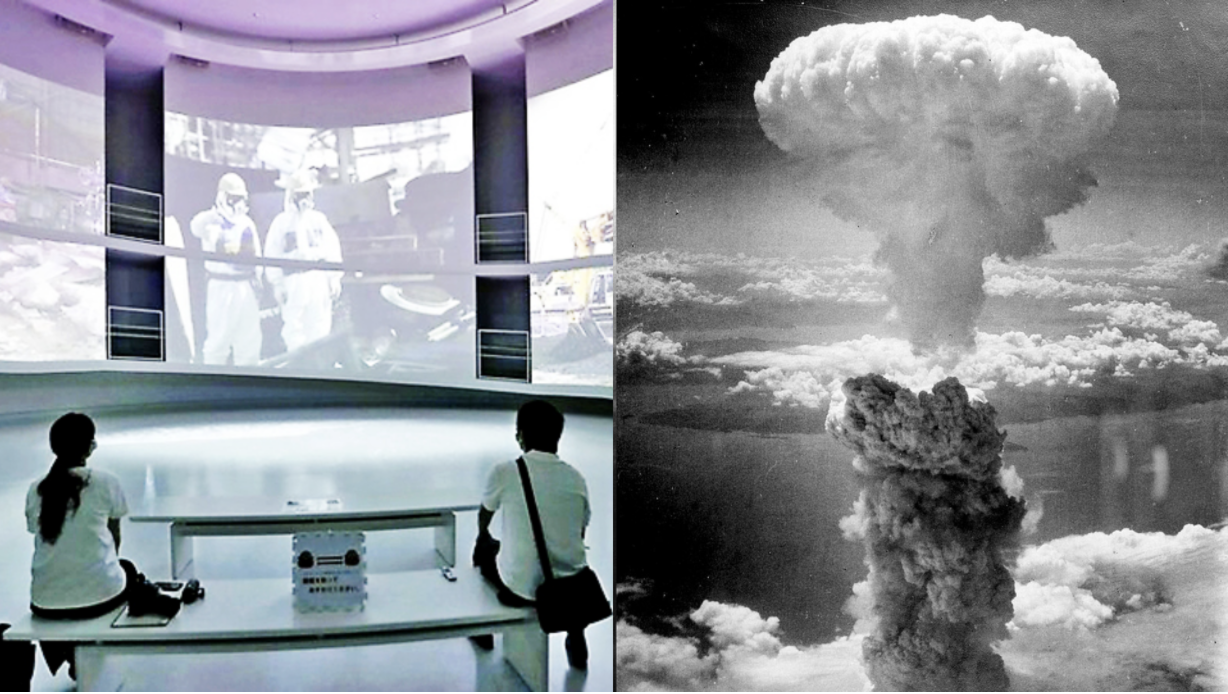

The Moon-Kim summit is also significant because of recent diplomatic history. Followers of South Korean policy towards North Korea will see if President Moon has taken lessons from previous South Korean presidents who met their North Korean counterparts, Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. Both favored policies of incentive-induced engagement with North Korea in the hopes that Pyongyang would curb its weapons program, called the “Sunshine Policy”. As we all know, despite the aid that flowed northbound in the early 2000s, North Korea did not abandon its nuclear program.

Fortunately, President Moon doesn’t seem to be going down that path. In an article for NK News, S. Nathan Park laid out his case for why this administration, while inspired by liberal presidencies of the past, does not seem to be making the same mistakes. The key difference is President Moon’s continued pressure on North Korea, which he describes as “pragmatic flexibility…between a military threat and an olive branch.”

That pragmatic flexibility has paid off for South Korea, which has proven to be an indispensable source in regards to diplomacy with the North. The April meeting between Moon and Kim may not have a global impact, but the outcome may help gauge the atmosphere of the Trump-Kim summit in May. The important question is not the significance of the inter Korean summit, but whether or not the United States will be paying attention.

- Kansas City: World War I’s Final Resting Place in America - November 9, 2018

- Moon Jae-in’s Elusive Peace - September 7, 2018

- Japan’s Diplomatic Vanishing Act - June 8, 2018