Food Scarcity in the DPRK

Access to food is an everyday concern for individuals living in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 10.7 million North Koreans, approximately 40% of the population, are undernourished and in need of food assistance.

Lack of food accessibility causes serious health issues, in vulnerable communities such as women, children, and the elderly being particularly at risk. Health scientists acknowledge an association between food insecurity and delayed development in young children, general risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes and high blood pressure, linkage to adverse effects on overall health, and in severe cases, can result in death. In the DPRK, recent droughts and the dismissal of foreign aid have prevented food security progress and in 2020, over 312,000 children were stunted and 1 in 3 women between the ages of 15-49 was recorded to have anemia.

The immediate years following Kim Jung-un’s ascent to power, 2012-2015 was a time to prepare for economic and agricultural reform. During this period, the agriculture sector laid the groundwork for policy implementation that aimed at incentivizing farmers and boosting production through the decreased size of work teams and new rules that allowed farmers to keep 30% of their production plus any surplus above production targets. From 2016-2020, the nation was preparing to achieve a full-fledged economic leap through the promotion of Kim’s five-year national economic development strategy. For agriculture, this included a “plot responsibility system” that designated small teams of farmers to farm, improve, and reap the benefits of an area of land that was no longer under the complete control of the larger cooperative. Critics, while avoiding explicit mention of the policy in news articles, did not agree with any move to more individual responsibility. A Kyongje Yongu (경제 용구) article stated, “Only by applying a guidance method that can strengthen collective unity and cooperation based on socialist and collectivist principles can [we] defend and adhere to the socialist rural economic system and fully display its superiority.”

However, the expected agricultural results were disrupted by strengthened sanctions against North Korea from 2016 to 2017, a substandard harvest in 2018 (recorded as the worst harvest in a decade with production 12% below average), flood damage that occurred in 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Factors that Led to Food Scarcity

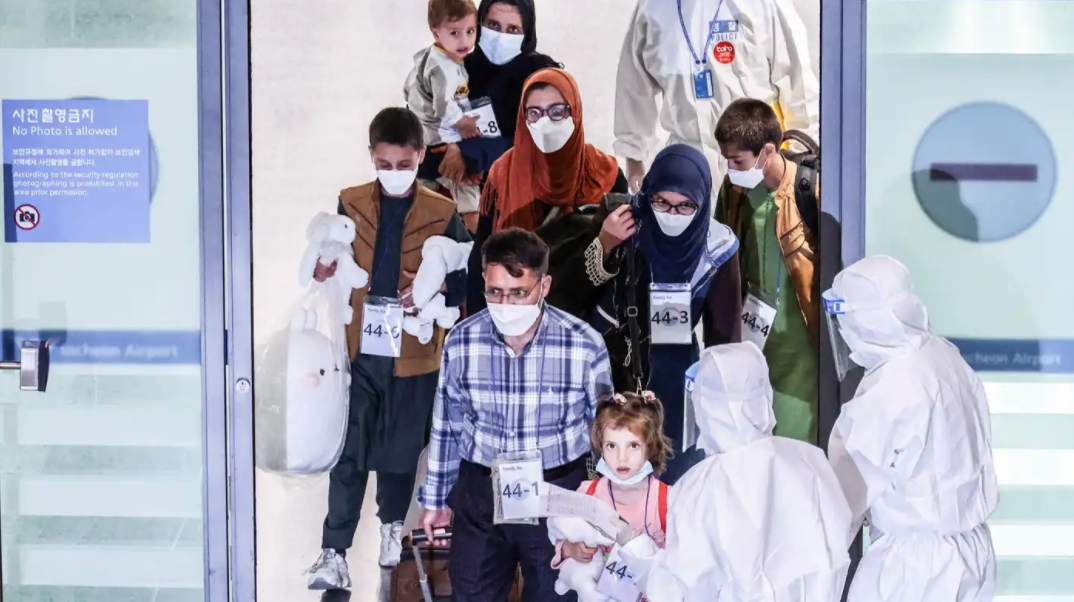

In response to the pandemic, DPRK authorities have enforced excessive COVID-19 measures to seal borders. Saying they were necessary to contain the virus, authorities built or upgraded fences, guard posts, patrol roads, and other infrastructure on the border that have almost entirely stopped unauthorized cross-border economic activity. This, in turn, contributed to severe shortages of food, medicine, and other necessities. Additionally, traveling abroad was banned and in-country mobility was severely restricted, thus hindering the import of food, fertilizers, farming equipment, and humanitarian aid. WFP staff reported very few relief items have been permitted to cross DPRK borders since August 2021 and before being able to provide aid staff were forced to undergo three months of quarantine. The last recorded WFP distribution occurred from January to March 2021 during which 891.5 tons of fortified food and 4,970 tons of raw food commodities helped assist 566,886 people. Following that, there has been no United Nation foreign staff or international NGO staff present in the nation. There is no expectation for border security to relax, and after two years of strict lockdown, humanitarian workers have only a skeletal presence in the DPRK. The exception is freight train operations between DPRK and China that restarted in January 2022. Food aid and medications such as glucose, antibiotics, and fever reducers were transported to the DPRK but freights were promptly halted in May due to a pandemic outbreak. Freight train operations have resumed as recently as the end of September.

From an outside position, a lack of data prevents a clear understanding of the situation on the ground. The latest information on harvest production was from 2020 and the latest information on North Korea’s Public Distribution System was from July 2021. Despite this, the international community has relied on innovative solutions and technology to have a deeper understanding of food accessibility in the DPRK. Data on food price fluctuations and satellite imagery are used to forecast agricultural production and predict possible food security trends.

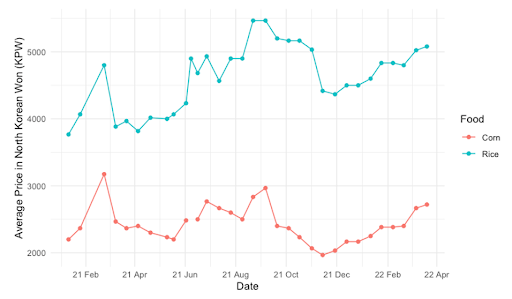

Commodity and transportation prices are also rising in North Korea. From 2021 to 2022, the price of rice rose by 21% and fuel prices almost tripled. Additionally, the price of corn is 52% higher since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shipping costs from China to Nampo, DPRK have increased three-fold. These concerns are further exacerbated due to the recent depreciation of the North Korean Won, which has depreciated 68% against the USD, and 39% against the Chinese Yuan within a year.

Graph. Source: The Korea Economic Institute of America.

Experts estimate that production of both winter and spring crops was likely affected by poor water supply from historically low snow cover, and snowmelts were the main source of water for crops. In the southern crop-producing areas of the country, severe rainfall deficits were observed in April and May, and this harmed the country’s potato production. These areas were hit again in July when they received half of the average monthly rainfall, and this factor possibly led to delays in planting. Although plentiful rainfall occurred during the first weeks of August, dry conditions returned in late August to early September. In sum, experts predict a drier than average winter in the year 2022 and a possibility in low snow cover for winter crop production.

The Central Committee plenary report published by the DPRK reviewed the economic situation and staked out a direction for 2022. The report is scarce in detail and concrete implementation plans, but includes the goal to “completely solve the food problem.” However, in early November, Kim launched unprecedented 40 missiles within two days between the Korean Peninsula and Japan. A research unit from the RAND Corporation, an American nonprofit global policy think tank, calculated that the DPRK economy lost more than $70 million when it launched 23 missiles; this is equivalent to the amount of money spent in importing rice from China in 2019 when they suffered from grain shortages. Soo Kim, a policy analyst focused on national security and policy issues in the Indo-Pacific at the RAND Corporation, agreed that the Kim regime is the greatest obstacle to getting international food aid to North Koreans.

Helping Hands Korea

While international organizations are barricaded from providing food aid to North Koreans, a grassroots Seoul-based NGO works around DPRK border regulations to provide relief. Helping Hands Korea (HHK) is a Christian NGO that aims to assist North Koreans in crisis despite border closures.

Established in 1996 by Tim and Sun Mi Peters, HHK has partnered with individuals and organizations worldwide that share a sense of urgency to provide food aid to vulnerable groups in the DPRK as well as assist defectors. HHK provides logistical support to escapees in China along an “underground railroad” to guide them to safe havens in neighboring countries. Catacombs, solely managed by Tim, is the sector of HHK that specifically focuses on fighting food scarcity through the deliverance of food, medicine, and clothing to vulnerable populations in the DPRK, especially orphans in impoverished areas, the handicapped, the elderly, and persecuted Christians. Since 1996, their food aid has included vegetable seeds, rice, biscuits, rice cakes, bread rolls, corn, flour, and dehydrated one-pot meals.

Tim and Sun-mi Peters, back, meet with children, most of whom lost their North Korean mothers due to forced repatriation from China. In 2012, Helping Hands Korea launched an informal foster home for dozens of such children near the provincial border between Jilin and Liaoning provinces. Source: Tim Peters, Korea Times 2022-01-06.

Though the work of HHK may be small, it is impactful. During food shortages, informal private farming on small plots of land, including kitchen or balcony gardens are used to grow crops such as cabbage, beans, garlic, potatoes, or maize. These small improvised gardens prove crucial in times of food scarcity and allow individuals to supplement the food they receive through the government’s Public Distribution System. HHK works specifically to provide individuals with seeds for makeshift gardens.

Personal Experience

I initially heard about HHK from a fellow ex-pat in a Kakao group chat. When I arrived at my first Catacombs meeting located about 50 meters from Samgakji Station exit two, I immediately felt welcome. Tim has a talent for joyfully greeting everyone as though they were an old friend, listens to stories in a deep manner, and seems genuinely interested in the well-being of everyone who walks through his door.

Meetings are held every Tuesday from 7-9 pm and consist of casual discussions ranging from daily happenings to global foreign affairs while scooping spoonfuls of seeds into small plastic bags to later be counted and transported to the DPRK. Most newcomers similarly discover Catacombs through word of mouth, which has fostered a cohort of curious individuals who tend to skew closer to young adults, with the average age being between 20 and 30 years old. Though Tim is motivated by his devotion to Jesus, the meetings are not explicitly religious and many volunteers do not identify as Christians. Catacombs welcome individuals of all backgrounds, including some North Korean defectors, which allows for valuable conversations that cannot always be found in academic settings. Though repacking and counting seeds may not be considered thrilling, a majority of development work is not. In my experience, Catacombs has provided the space to accomplish meaningful work, connect with like-minded individuals, and gain a sense of community, no matter how small.

Bags of Korean cabbage seeds are repackaged and stored in one corner of the Seoul gallery. Source: Korea Times photo by Shim Hyun-chul.

Conclusion

Tim and Catacombs continue to have a hopeful outlook despite the challenges they face. Currently, there is no indication of the border reopening for international staff and food commodities, and this impacts Catacomb’s ability to send seeds across the border. Seeds are often redirected to other nations in need; recent shipments have been made to Nepal and Madagascar, both vulnerable countries to food insecurity. Packages of seeds must often take detours to neighboring nations where they are intercepted by North Koreans working abroad and brought across DPRK borders through holiday visits. For example, a future shipment of seeds is scheduled to travel to Istanbul, where they will be intercepted by Russian workers who aim to bring the seeds across DPRK borders.

Food security and nutrition in the DPRK remain a priority for experts watching from abroad. Late planting and late season dryness may lead to crop production problems in 2021-2022 harvest and increased food and fuel prices continue to deteriorate the food security situation and put increased pressure on poorer families. Despite border closures and operation suspensions, it is crucial for the international aid community to maintain commitments from key partners and donors and have standby procedures for swift execution in the instance of border re-openings. Meanwhile, local NGOs such as HHK and volunteers are doing everything in their power to provide assistance to North Koreans in crises.

Kayla Kingseed is from the United States and is pursuing her Masters in International Trade Finance and Management and Peace and International Cooperation at Yonsei GSIS. Her passion lies in NGO effectiveness and gender equality. Kayla comes from a background in financial mathematics and has also worked within the IT sector specializing in cybersecurity education. She is an avid rock climber, cat lover, and enjoys immersing herself in art, music, and the experience of cuisines from all over the world.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024