Four hundred years ago in 1618, one of the longest and deadliest conflicts in human history erupted in Europe. The Thirty Years’ War was the violent finale to the Protestant Reformation triggered 101 years prior by an unsuspecting Martin Luther. Luther supposedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses on the front door of a church to get the attention of the Archbishop of Mainz. The theses raised questions about the Catholic Church’s practice of selling plenary indulgences, but they went deeper, questioning the need for priests as intermediaries. The Catholic Church immediately framed Luther as a heretic and refused to acknowledge Luther’s main complaints in his Ninety-five Theses.

Luther set in motion the Protestant Reformation, which would go on to shake Europe to its core for over a century until the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648 with Peace of Westphalia. Originally a revolt by Protestant German states opposing Ferdinand II’s forcing of Catholicism on the Holy Roman Empire, the Thirty Years’ War became the biggest religious war ever fought in Europe. It was also a full-blown political war that subsumed the France-Habsburg rivalry, one of the central storylines of European history.

Every student of international relations is all too familiar with this war, the Peace of Westphalia, and the resultant Westphalian system; they are some of the first topics of any International Relations 101 class. The Peace of Westphalia cemented the idea of nation state sovereignty and effectively ended European wars of religion by recognizing Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism in the Holy Roman Empire. An equally significant, though less observed, product of the Thirty Years’ War was the birth of first generation warfare (1GW), characterized by lines and column tactics. With state sovereignty came the right to maintain and organize national militaries, compared to before when wars were fought by armies controlled by religious orders or rich individuals, usually princes or lords of fiefdoms. The Thirty Years’ War gave rise to massive armies, funding of which was possible only for the giant economies of nation-states.

Big armies and big battles characteristic of 1GW required order and organization, both on the battlefield and in military culture itself. This generation of warfare reached its peak with the Napoleonic War in which French Revolution-inspired patriotism, and its resultant enthusiasm, provided a steady stream of manpower needed to support Napoleon’s massive armies. The distinction between soldier and civilian was one conceptual and pragmatic product of 1GW, as well as its accompanying uniforms, salutes, drills, and units.

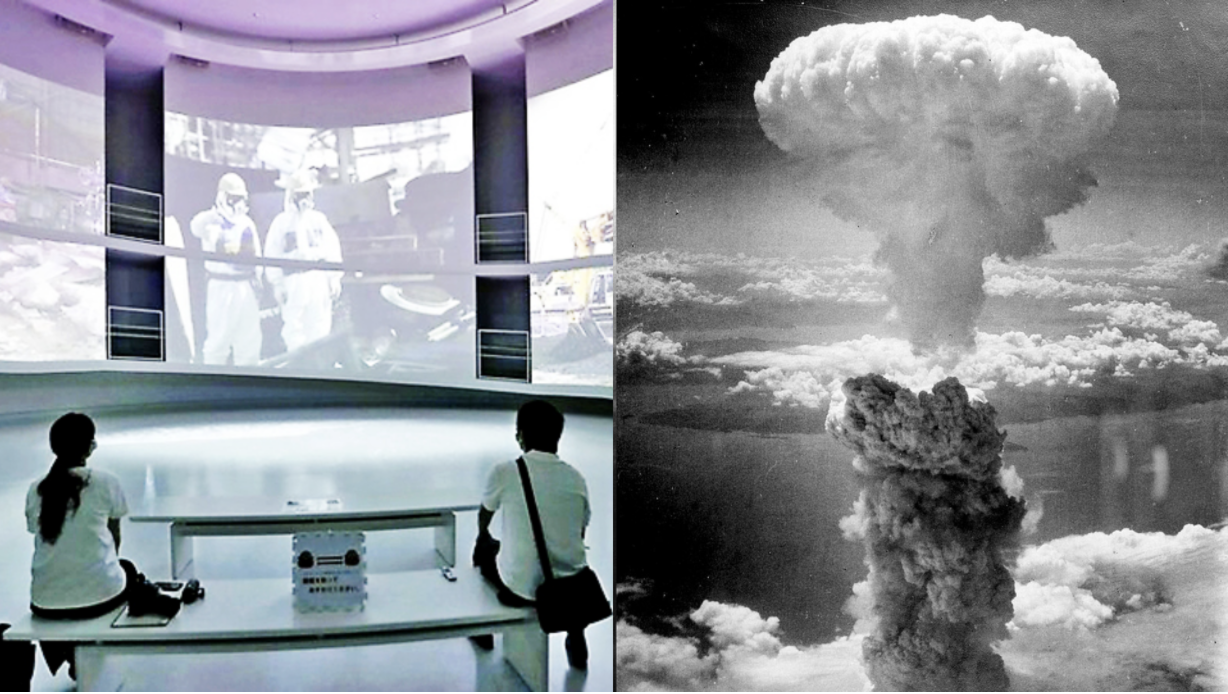

Then came second generation warfare, which kept the lines and columns of 1GW but increased its focus on smaller units. World War I and the American Civil War are quintessential examples of wars of the second generation. Third generation, the advent of which was World war II, was all about movement, speed and maneuvering. During World War II, Germany’s blitzkrieg, using massive firepower in order to penetrate enemy lines, showed the true superiority of speed and movement over static lines and columns. More movement meant smaller units were given much more flexibility and freedom than in the past, signaling the breakdown of traditional military command and control, a process continuing to this day.

Four centuries later, the world of today, is witnessing warfare’s regression back to, or at least adoption of characteristic of wars from before first generation, before the rise of states, before the Thirty Years War. This kind of warfare is now called fourth generation warfare (4GW), which is a reversal of the direction of warfare from hyper-organization to disorganization, from centralization to decentralization, and from interstate to intrastate, cultural, or ideological. There has been enough of a regression that we can no longer say with certainty that the Thirty Years’ War was the end of religious wars, or war between peoples.

Of course, there have been wars in the past that have employed hallmark tactics and strategies of 4GW. The Spanish partisans of the Peninsular War hounded Napoleon’s formidable, but inflexible army, and gave birth to the term “guerrilla.” However, 4GW is significant not for its novelty, but rather for its increasing prevalence.

Big states, with the exception of Great Britain, have had an abysmal record against 4GW forces since the end of World War II: the French in Indochina and Algeria; Soviets in Afghanistan; and Americans in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. States’ armies, rightfully so, are designed, trained and maintained to fight against other states’ armies. Yet, these incredibly well equipped, well trained, and well serviced armies are more frequently asked to fight wars they are simply not designed to fight against, with atypical state or non-state actors.

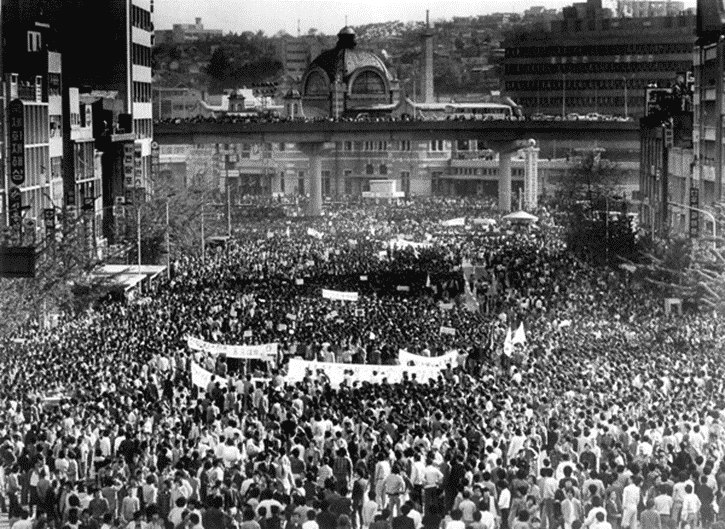

Gone are the days of uniformed armies meeting head to head on the battlefield, attempting to outmaneuver or break through enemy lines. Instead, the world has returned to wars among people: disorganized, unprofessional, and decentralized. A group of disgruntled insurgents can never win a war against a state by fighting on even ground with traditional methods, or playing by the rules set in the Geneva Convention or in formal rules of engagement. The capability gap between states and non-state actors has never been greater. Recognizing this gap and the need to find advantages, 4GW forces (guerrillas, insurgents, terrorists, rebels) have taken warfare back to the medieval era.

Where do we go from here? Militaries around the world started their adaptation to this new threat environment decades ago, and they have progressed especially rapidly since the United States’ experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. The British adopted their famous Briggs Plan in 1950 during the Malaya Emergency, a rare example of a state actor achieving thorough success against a 4GW force. The US Army’s Field Manual 3-24 is an evolving guideline that lays out the context for understanding – and solutions for defeating – insurgencies.

As warfare throws itself back in time, adaptability and flexibility will be paramount for success, just as they have been in every generation of warfare. The fundamental nature of warfare itself has not changed, and many military leaders, including US Secretary of Defense James Mattis, is correct in pointing out nothing about 4GW is really new. At the end of the day, wars are still fought for political objectives and motivations; the means of achieving such goals have changed from one generation of warfare to the next. However, such men also understand that wars are no longer won and lost just by armies trying to outmaneuver each other.

This trend of increasing intrastate, civil conflicts and declining interstate conflicts is likely to continue. with prolonged civil wars and domestic conflicts erupting along ethnic and religious lines, oftentimes drawing bigger powers into the picture, just like the Thirty Years’ War did. States and their militaries are now tasked with preparing for and winning two radically different wars: wars against states and wars against people. In certain ways, the task itself is unfairly demanding for organizations as big as militaries. Bureaucracies are naturally inflexible and task-specific and yet, history teaches that adaptation is a necessity, not a choice.

- Defining Denuclearization - April 24, 2018

- Hold the Horses of Optimism: Donald Trump-Kim Jong Un Summit - March 15, 2018

- China-South Korea THAAD Rapprochement: Winners and Losers - February 8, 2018

1 Comment

Cynthia donnelly

7 years agoThanks for explaining many things that i did not understand, and doinig it in clear, simple, and unpretenious language. Love Your writing style!

Comments are closed.