“Not knowing what is happening makes you crazy and terrified because you don’t know what to believe,” said an immigrant detained in Japan’s immigration detention centers in an article on The Japan Times about the situation of immigrant detainees amid the spread of coronavirus. Detainees interviewed in the article expressed worries about their safety since social distancing is not practiced where they are detained, and they are kept largely in the dark about the pandemic. Cases of coronavirus infections in Japan have continued to rise, raising concerns about not only the well-being of the general public but also that of detainees, who are often more vulnerable to the pandemic. Since detention centers often lack space, are poorly ventilated, and provide detainees with very limited medical care, those in detention are put at even greater risk of infection. Just as it unmasks and exacerbates social inequality in many countries, the pandemic illuminates Japan’s ill-treatment of detained irregular residents (asylum seekers, visa overstayers, and other foreigners whose visas have been revoked), which has been ongoing for years.

Through professor Blackwood who teaches sociology at Tokyo International University and has done research on immigrants, I came to learn of the Ushiku Detention Center (East Japan Immigration Center). From 2010 to 2018, there were a handful of detainees’ deaths caused either by suicide or illness due to lack of medical care and instances of self-harm. Many detainees, frustrated with the living conditions in the center and long-term detention have gone on hunger strikes to protest, one of which took place last December. According to Professor Blackwood, “One man that participated in the strike used to be an accomplished wrestler in Iran. When I went to see him last week, he was so malnourished and weakened from the strike he couldn’t even lift his head to look at me. It appalled me, seeing him like that.”

It appalled me as well. Ushiku Detention Center is an all-male detention center and one of the many facilities in Japan where irregular residents are detained while waiting for the government’s decisions on their cases. It concurrently detained between 320 and 325 people in recent years. Detention is not the only option, though the alternative is no better: repatriation to their home countries can mean facing persecution or economic hardships or losing contact with the family they have built in Japan.

(Ushiku Detention Center/Photo via Kyodonews)

Staying in Japan, however, means being stripped of everything an ordinary person takes for granted: access to the internet, entertainment, and even privacy. According to a report by Tanaka Kimiko and Miriam Wattles of Ushiku no kai, a group advocating for the human rights of foreigners detained in Japan, surveillance cameras used to be placed in detainees’ shower rooms to monitor their behaviors. Detainees are reportedly kept indoors 15 hours a day and have only a television set to entertain themselves. Provisional release is sometimes granted, though not with much freedom: detainees are not allowed to work, own cell phones or bank accounts, and must not leave their registered area of residence during the release. In fact, the release is more of an effort to appease frustrated detainees and motivate compliance than to ameliorate their sufferings, the report concluded.

What beckoned these people to Japan in the first place, only to endure this harsh reality?

The biggest group of people currently detained at Ushiku are Iranians. For the very first Iranians that came to Japan, the push factors were the war with Iraq and economic hardships, and the pull factors were Japan’s peace-loving image, low crime rates, and a booming economy. Japan’s soft power has a role to play as well. Growing up watching Japanese soap operas, one Iranian at Ushiku that I knew of formed an extremely positive image of Japan. Though he first arrived in Finland after fleeing his country, he did not seek asylum there but continued his journey to Japan under the belief that the country would warmly take him in. He learned too late upon arrival that fiction is not reality. He asked to be returned to Finland where his application for asylum would have a better chance of being accepted, but this request was not entertained. He was detained at Ushiku from November 2015 to the fall of 2019, then went on a hunger strike and was granted provisional release. Though he was told by the immigration authorities he could renew his release by showing up at the center after two weeks, he did not, having learned that other detainees were locked up when they checked in to renew their release. He presumably has become a fugitive since then.

Filipinos make for the second biggest group at Ushiku, and the very first Filipinos came to Japan in hopes of making money and to flee the political and economic crisis that beleaguered the Philippines in the 1980s. Instead of employment opportunities, many get trapped in prostitution or human-trafficking rings and are at risk of deportation. Many Sri-lankans, Vietnamese, and Nepalis at Ushiku are young workers who came to Japan seeking work. They stayed past their visa expiration dates in order to continue working in Japan and were subsequently detained.

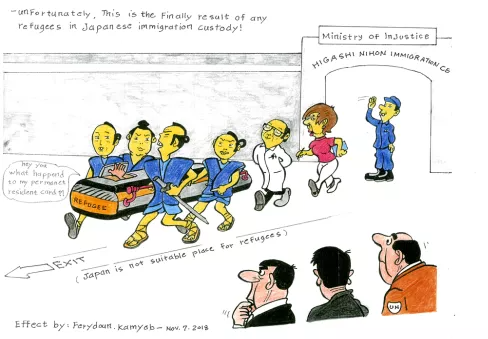

These anecdotes seem to have little bearing on the Japanese government’s immigration policy. While accepting increasingly greater numbers of immigrants into the country, the government actually devises policies that make integration and obtaining Japanese citizenship ever more elusive. To be eligible, those seeking Japanese citizenship must have stayed in Japan for ten years uninterrupted by the time of their application. This proves impossible, for instance, to those coming to Japan to work on the Technical Intern Training Program, who must return to their home country every five years to renew their visas. Not to mention that the internship program, one of the government’s much vaunted immigration policies, is often found to involve practices that violate trainees’ human rights. Many trainees have their passports withheld, are forced to work overtime, are underpaid, and are sometimes bullied at the workplace. Given these harrowing facts, it’s not surprising that Japan has the lowest refugee acceptance rate among developed nations: just 0.1% as of 2017 due to an extremely restrictive interpretation of refugees and the misguided notion that most asylum seekers are fake refugees.

Several things account for these unsympathetic policies towards irregular residents, first of all, the Japanese government’s dehumanizing view of irregular residents as economic goods rather than humans. In the 1980s when the economy of Japan was booming and unskilled, cheap labor was much needed, Iranians fleeing violence and poverty in their countries could come to Japan to work without having to obtain a visa. Their economic worth to Japan was evident then. But when the economy went through hard times in the 1990s, migrant workers no longer had any worth and became something of a burden. This recurred in 2008 when Japan entered a period of recession, and Brazillian workers, no longer of any use, were urged to leave Japan. Those refusing to return to their home country became irregular residents to be detained.

(Foreign workers are essential to keep farms running in such areas as Gunma Prefecture, known for its vegetables/ Photo via Reuters)

Likewise, in the assessment of Shiori Yamao – leader of the opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan – the recent Technical Intern Training Program has less to do with helping less developed countries in the region and more to do with supplying Japan with cheap, low-skilled, disposable workers. It isn’t hard to discern who is on the winning side of this policy. Japan, given its labor shortage, gets to enjoy large numbers of workers while trainees on internship programs are often exploited and hardly obtain any valuable skills that they might take back to their home countries. These policies indicate not a change in attitudes towards immigration and foreigners but rather a new means of exploitation. Favorable terms expire once the persons enjoying them lose their worth – a “use-it toss-it” mentality, as Japanese Studies scholar Jeff Kingston calls it.

Besides, Japan has never been too keen on accepting foreigners into its society, and this sakoku mentality, so named by Japanese scholar Mayumi Itoh for the self-imposed isolation implemented in Japan during the Edo period, persists. Of the Japanese’s views on foreigners, writer Marie Mutsuki Mockett in her book “Where the dead pause, and the Japanese say goodbye: a journey” said: “There is also an element within the Japanese culture that persists in telling itself and others that it is special and unlike any place else in the world. The Japanese, in fact, are so special that only they can understand their culture. A gaijin (foreigners) cannot be expected to ‘get it’.” Negative portrayals of immigrants as perpetrators of violence and sex crimes as well as exaggerated depictions of cultural clashes between them and the locals in the media also hinder positive attitudes towards irregular residents in Japan.

The Japanese are somewhat rightfully worried about foreigners’ abilities to integrate into Japanese society. Many Japanese people complain that Kurdish immigrants, for example, are normally louder than the Japanese in public, not as punctual, and do not follow garbage disposal rules. While cultural differences may indeed get in the way and make working alongside Japanese natives difficult for foreigners, such differences are not irreconcilable. In fact, integration can be facilitated if the government takes steps to train immigrants in the language and educate them about Japanese social norms as well as teaching locals about other cultures to enhance mutual understanding, which nonprofit organizations such as Japan Association for Refugees have already done.

(People protesting against legislation that accepts more foreigners into Japan/ Photo via South China Morning Post)

The factors that lead to unfriendly policies and attitudes towards undocumented immigrants in Japan mentioned above are also factors that shape anti-immigration sentiments in other parts of the world. In Japan, as in advanced nations, irregular residents are welcomed only insofar that they can demonstrate their economic benefits to the host countries. Since economic immigrants and asylum seekers in advanced countries such as the United States or European countries are often perceived to be poorer and more dependent on social welfare than they actually are and are thus of little benefit to the countries that host them, many local people understandably do not welcome them. Concerns about the dilution of local culture and negative stereotypes of irregular residents as criminals, fake asylum seekers, or unable to integrate are not unique to Japan either. Fears of Islamization and losing demographic grounds incited by increased immigration are present even in countries much more cosmopolitan than Japan, such as the United States.

The Iranian wrestler who went on a hunger strike is still in very bad shape. The strike has left him physically weak and he can no longer eat solid foods or take in nutrients. If the current Coronavirus lockdown is taking a toll on our mental well-being, imagine what it must be like for people who have been detained for years at Ushiku. Although his lawyer is working round the clock to get him released, it remains uncertain when and for how long he will be granted freedom and if it will actually do him any good. In fact, though Ushiku Detention Center has temporarily released 20 detainees in response to the possible spread of coronavirus among them, this release does not necessarily give them more protection against the pandemic. Irregular residents on provisional or temporary release are not entitled to national health insurance and cannot work since, as stated previously, they cannot open bank accounts or own phones.

(Rooms of people who are detained at Ushiku Detention Center/ Photo via ElevenMyanmar)

Up until now, the predicament of irregular residents in Japan has received relatively limited international attention, thus giving the government no pressure to revise their policies and better accommodate the needs of irregular residents. This is partly because communication with the outside world of those detained in Japan’s detention centers is subjected to more control than that of those detained in other countries, such as Britain or Australia, making it hard for detained irregular residents to tell the world their stories. But the current pandemic, while disastrous, may prompt the Japanese government to rethink its policy.

The spread of Covid-19 has shown that governments cannot afford to continue the ill-treatment of irregular residents. Singapore, for example, is now grappling with mounting cases of coronavirus infections among the migrant community since officials have overlooked this vulnerable population. Japan may be faced with the same situation unless it makes attempts to improve detainees’ welfare. Viewing irregular residents only in terms of their economic worth and leaving them to live in crowded, unsanitary places and with limited medical care may seem convenient, but the pandemic has shown us that this may come at a cost. Irregular residents are not limited to the labels that have been forced upon them – illegal immigrants or detainees – nor are they disposable economic goods that are there only to service the economy of Japan. They are humans whose welfare must be attended to, and it’s time the Japanese government and public start to treat them as such.

Luu is an International Relations student at Tokyo International University. Her interests include cultural studies, gender relations, and media representations. She believes that most problems in the world can be solved if people start adopting a more human-centric standpoint.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024

1 Comment

LGBT+ in Vietnam: Acceptance in Conformity or Furthering Heteronormativity - Novasia

5 years ago[…] Luu is an International Relations student at Tokyo International University. Her interests include cultural studies, gender relations, and media representations. She believes that most problems in the world can be solved if people start adopting a more human-centric standpoint. She has previously written for NOVAsia. […]

Comments are closed.