Source: Korea Joongang Daily

The year 2021 started off on a rather tumultuous note for several celebrities and athletes in Korea. Allegations of bullying in the past, most of which were admitted to be true, put an end to the career of some. Celebrities like Ji-soo, the actor, and Na-eun from the female idol group April, were removed from a drama and several other idols and actors in the industry too were caught in the crossfire of allegations. In the sporting world, volleyball player Park Sang-ha announced his retirement after admitting to a bullying allegation, and the female twin stars of volleyball, Lee Jae-yeong and Lee Dae-yeong, were banned from playing until further notice. The allegations against celebrities are just the tip of the iceberg of a bigger social malady plaguing the Korean society.

A survey conducted in September 2019 by the Education Ministry reveals that 1.2 percent of 130,000 student respondents of elementary, middle and high school experience bullying whereas 0.6 percent of the respondents admitted to having bullied others. The elementary school students reported the highest bullying rate with 2.1 percent. Considering the age of elementary school students (7-12 years in international age), it is of real concern why children of such a young age engage in abusive behaviours.

Before proceeding further in this discussion, it is pertinent to consider what amounts to bullying. According to the Oxford Learner’s dictionary, bullying is “the use of strength or power to frighten or hurt weaker people”. In schools, bullying takes different forms which includes physical abuse like beating, pinching and hair-pulling, name-calling or verbal abuse, extorting money or food and even ostracism.

Bullying became an issue in Korea over the last decade after several appalling incidents rocked the nation. In 2012, Lim Jee-young, a 13-year-old boy, committed suicide and left a note giving details of how brutally he was bullied. In 2017, the case of a 14 year old girl being beaten by some of her peers in Busan went viral after a picture of her battered face made rounds on social media. An outrage against it erupted because the bullies were exempted from criminal charges under the pretext of being underage. Consequently, it propelled the people to advocate for the lowering of the Juvenile Protection age from 14 to 13 years as those aged 10-13 are not held criminally accountable for criminal law violations.

However, even as a lot of attention is directed to bullying in general, cases of bullying of multi-ethnic (mixed-race) children receive less exposure. Bullying of multi-ethnic children warrants separate attention because its nature is different; multi-ethnic children are targeted simply because they are different. According to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in 2016, 5 percent, or 3,090, of 61,812 multi-ethnic students in Korea aged between 7 and 24, experienced bullying and abuse at school, a proportionally higher percentage as compared to the general bullying statistics. Also, a 2014 data from the Ministry of Education disclosed that bullying is one of the causes of high drop-out rates from school among multi-ethnic children, which is purportedly four times higher than among Korean students. It is important to note that according to Statistics Korea published in September 2019, multicultural households amounted to 335-thousand, constituting over a million people. The fact that they comprise approximately 2 percent of the total population imply that their presence is quite significant. Moreover, the ‘youth statistics 2020’ released by Statistics Korea, report that multicultural students numbered 137, 225 in 2019, accounting for 2.5 percent of the age group between 9-24 years.

In an interview with the Korea Times, a Korean language teacher at Guro Middle School where about 20 percent of its students are multi-ethnic children, revealed that multi-ethnic students in their school were often discriminated against and treated as second-class citizens by their peers. There are also cases when the discrimination turned violent. In 2017, a 12-year old Korean-Vietnamese boy lost an eye as a result of being bullied by another student. In 2018, another 14-year old half-Russian boy lost his life after falling off a building while running away from bullies. There could be more such stories which did not attract media attention or were unreported because a lot of multi-ethnic families also come from humble backgrounds like farming households.

Source: Screen capture from youtube channel of Griffin Chaeng

That the bullying of multi-ethnic children is prevalent, can also be seen from the confessions of multi-ethnic celebrities who were victims of bullying. Celebrities like Yoon Mi-rae, Michelle Lee, Jeon Somi and more, revealed that they were bullied for being different and some even mentioned being called 잡종 (jabjong), meaning crossbreed. Another notable example is Han Hyun-min, a young model in Korea, whose father is Nigerian and mother is a Korean. He is known to speak only Korean because he was born and raised in Korea, but because of his looks, some Korean parents forbade their children from playing with him and at times he was questioned for being in someone else’s country.

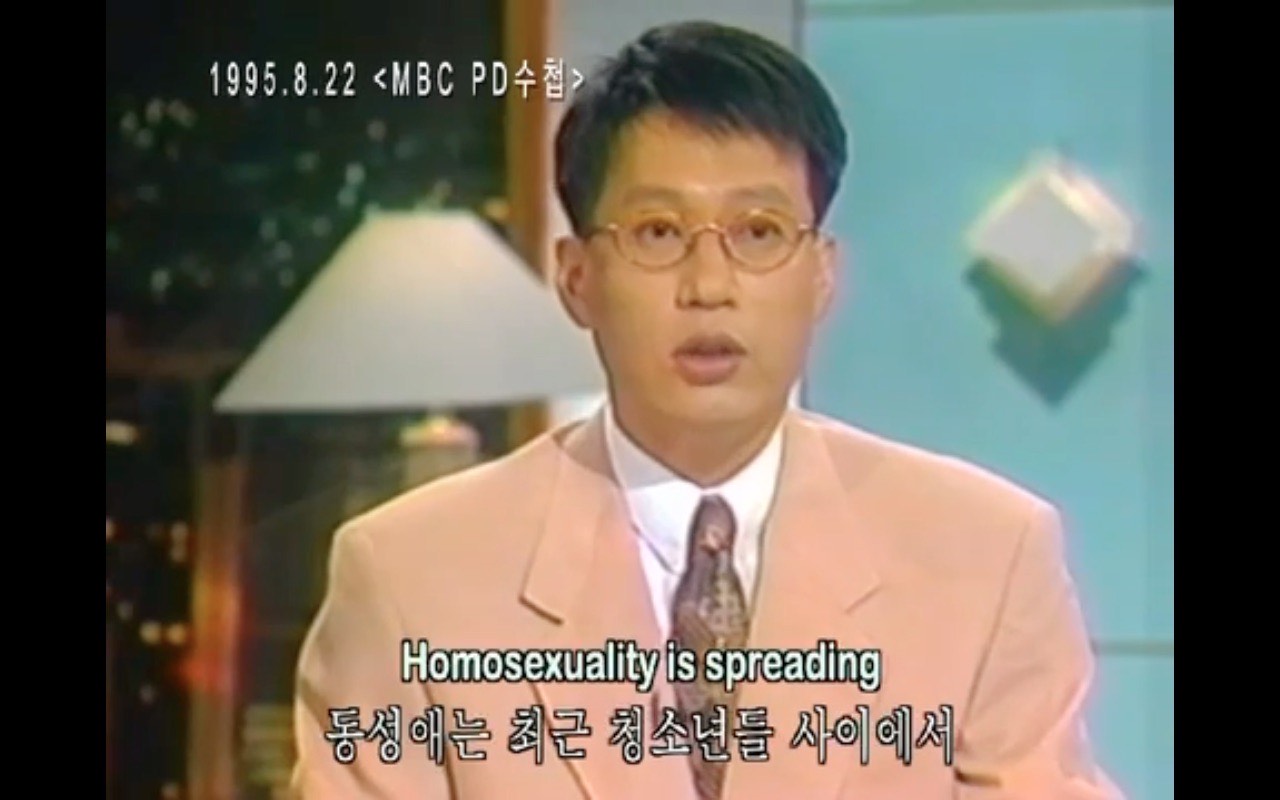

With all these stories out there, why is there little public denigration of such treatment towards multi-ethnic children and community at large? Perhaps, the answer is the ramifications entailed by such a discussion which will reveal deep-seated societal discriminations against people who are not pure Koreans in a largely homogenous society – an uncomfortable truth to deal with.

Source: AFP

How do we understand the high incidence of bullying in the Korean society?

Some experts like Joo Mi Bae, a clinical psychologist contend that competitiveness in school makes students see each other as competitors and not as friends where students who lag behind use bullying as a form of control to boost their image. A 2009 report by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs disclosed that students in Korea studied about 3 hours more per day than those from other OECD member countries. Others are of the opinion that budget cuts in schools increased the proportion of short-term contract teachers who serve as home-room teachers with extra responsibilities that prevent them from devoting enough time to the students, resulting in bullying tendencies going unchecked. Data compiled by Saenuri Party lawmaker Kang Eun-hee reveals that teachers increasingly avoid taking responsibility for the students and it is cited that the short-term nature of their tenure is to blame.

However, these explanations do not provide in-depth consideration into the possible motivations and fail to account for the bullying of multi-ethnic children which is rampant and associated with a deeper prejudice based on skin colour and appearance. Actions of some parents, like in the case of Han Hyun-min, when sometimes parents stop their children from mingling with multi-ethnic children, lead to ostracism and reveal existing prejudices against multi-ethnic communities in the Korean society, as displayed in the statistics which show that 34.1 percent of those who responded to having been bullied in school were said to have been isolated by their classmates.

Moreover, in some schools, the teachers themselves seem to exhibit prejudices against multi-ethnic children. To give an example, an award-winning teacher in Suwon was fined 3 million KRW (approx. 2660 USD) for discriminating against a multi-ethnic student in the class. Another elementary teacher in Gimhae also admitted that it took a few years for her to change her thoughts that having more multi-ethnic students in school was problematic.

What this indicates is that a solution to bullying of multi-ethnic children will be a long-drawn movement to change the socially ingrained prejudice and will need to start from the adults and the community at large, as prejudices among children are internalized through social conditioning.

So, what steps have been taken to ameliorate the situation of multi-ethnic children?

The Government has been making some efforts to ensure the well-being of multi-ethnic families. Through Government efforts, several alternative schools focussing on education of multi-ethnic families have been established since 2012. The argument is that these schools help students to gain confidence and enable them to bond over similar experience.

But in the long-term, it is only widening the rift between native children and those of multi-ethnic backgrounds. Hence such segregation can do more harm to the society as it takes away even the chance of inter-mixing and normalizing the presence of the perceived ‘other.’

Another move by the Government came last year in December, when the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family announced that the Multicultural Family Support Act will be revised to legally ban hate speech in order to eliminate discrimination against multicultural families. But the question is, will it be enough to put an end to all forms of bullying?

Source: Dramabeans, Itaewon Class Episode 11

It is apparent that what the Korean society needs is sensitization towards the presence of multi-ethnic communities. To some extent, baby-steps towards sensitizing Koreans to multi-ethnic families can be seen intermittently on Korean shows and dramas, one example being the story of the character, Tony Kim and his grandmother in the hit drama Itaewon Class, which portrays a poignant story of a woman who learnt to accept her Black grandson and overcome her racial prejudice. There are also several multicultural families active on the Korean variety show- Return of Superman, but these are but few examples. Overall, we are yet to see a K-drama romance or a family story of a multi-ethnic couple as the lead characters. Through its ability to shape public opinion, a more proactive media will definitely help in building a positive image of multi-ethnic families in the minds of the Korean public and may perhaps prove to be the silver lining from their sad predicament.

To conclude, the bullying issue in Korea needs to include the racial dimension in its efforts to resolve it. Without including it, efforts will continue to fall short. The public outcry for tougher punishments which followed the horrifying incident of the middle school girl’s case in Busan, is not enough. Punishment, though necessary, will not stop bullying from recurring. And, instead of deriving satisfaction from public reprobation of celebrities for their past as a bully, perhaps, it is time for the Korean society to ask where and how the society is failing its children, and specifically multi-ethnic children.

- Race Against Time: South Korea’s Role in Mitigating Climate Change - September 8, 2021

- Countering Oppressive Ideologies: Reasons Why India Cannot Write off Liberal Arts and the Social Sciences - July 21, 2021

- Is there a Silver Lining in the Plight of Multi-Ethnic Children Against Bullying in Korea? - May 7, 2021

1 Comment

박소희

4 years agoThank you so much for shedding light on realities.

Comments are closed.