Having enjoyed a surge in global popularity over the past few years, more attention than ever was given to South Korea’s politics as Yoon Suk Yeol plunged the country into chaos on December 3rd – declaring martial law for the first time in 44 years. Modern South Korean history is filled with martial law, and its people have experienced over a dozen instances of the military taking (temporary) control over the government; the public has not always been very supportive of these instances. There is a long history of popular uprisings against authoritarian regimes, tracing itself back as far as the 1919 March 1st Movement. After South Korea democratised in 1987, or 1994 depending on who you ask, there were a number of times that a large portion of the people felt that it was time for them to actively participate in the political process by showing their support for or against a cause.

This was also the case the past few days as all over South Korea, citizens poured into the streets to protest, both in favour and against, the attempted power grabbing by Yoon. These protests have remained peaceful and despite what one might assume would have been a gloomy night full of angry chants, turned into a public event where young and old came together to show their support for democracy.

Protest Industry

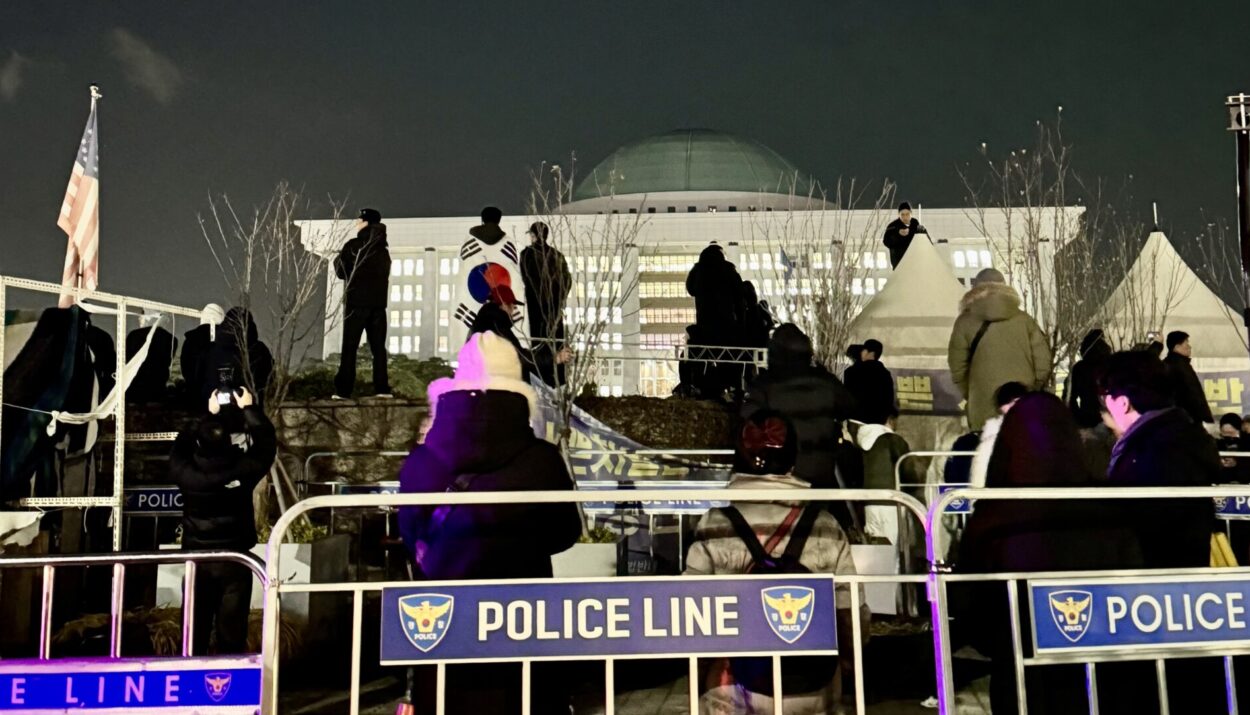

Protestors were quick to organise, with around 1000 people showing up in front of the National Assembly in the middle of the night as South Korea’s Parliament was frantically trying to organise a vote against the martial law. As citizens literally threw themselves in front of the military that was attempting to enter the Parliament to stop the vote, people were quick to print out pickets calling for an end to martial law. About an hour after those pickets showed up, Parliament was able to pass a motion that forced the president to call an end to military rule that lasted about 330 minutes – the shortest in Korean history so far.

All eyes were locked on South Korea the past few days, as emboldened citizens went to the streets with their pickets, flags, and candles – the main protest tools that have been highly visible during the candlelight vigils of the past two decades. Famously, back in the winter of 2016-2017, people gathered every weekend to call for the impeachment of then-President Park Geun-hye for corruption and abuse of power, with success. Over the years, the candlelight vigils have become not only a symbol of peaceful demonstration but a symbol of South Korea’s mature democracy.

A coup in the digital era

A protestor holds up an NCT lightstick on December 9th. Source: author

This time, a new hot item was visible lighting up the main road around the National Assembly: light sticks – a common cheer tool used by K-pop fans. The usual protest songs – written decades ago by those protesting against the Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan regimes – have been replaced by catchy K-pop tunes and slightly retouched lyrics to include the political message. Classic tunes by Psy, G-Dragon, Girls Generation, and other idols that the current 20-year-olds grew up with passed the revue, along with more recent fan favourites such as Whiplash by AESPA and Fighting by BBS. In tune with the season is also a rewritten version of ‘Feliz Navidad’ where “I wanna wish you a Merry Christmas” was replaced with “If Yoon Suk Yeol **** off, then it’s a Merry Christmas.”

Growing up with the fastest internet speed on the planet, the current MZ generation was quick to mobilise using the tools that they grew up with: social media. Instantly, memes about Yoon and his failed coup attempt went viral as people brought out leeks and toy wands to have something to hold up during the protest. People brought flags and posters for organisations such as the “Overconsumption of Idol Merch Alliance” or the “Red Blood Sausage Gukbap Association,” customs made less than a day after the martial law was lifted.

A new generation

An older man talks to a group of young protestors in front of the PPP office on December 7th. He explains how they should save their energy for tomorrow and go home for the day. Source: author

All this is a sign of a torch being passed down to a new generation. Those who were there protesting during the Seoul Spring of 1980 and the June Uprising in 1987 have become part of the system – ruling the country and running its economy. The so-called Undongkwon of the Minjung Movement was faced with a harsh reminder of days of yore and that their fight was not over yet. When martial law was lifted but a crucial impeachment vote in the parliament failed to pass, effectively allowing Yoon to retain power and stage a second coup attempt, most protestors were quick to go home frustrated and disappointed. This hopelessness was countered by those who remained chanting for impeachment at the gates of the Parliament until the early morning.

Those who participated in the social movements of the 1980s have become parents themselves, their children learning about their parents’ and grandparents’ efforts to fight for democracy since the early days of their young republic, witnessing the protests in 2016 and now being there in front of the National Assembly in 2024 – knowing that no wind could blow out any lightstick, they started chanting: “I want to live in a country where my only worry is fangirling!”