In South Korea, it is not uncommon for elementary students and their parents to obsess over the standardized test grades of children as young as second or third grade. This is because such tests are a key metric in future applications to special middle schools, then to high schools, and eventually elite universities. However, much of this system is set to change dramatically within the next few years, in ways no one seems able to fully predict.

In November, the Korean government decided that it would close down all “autonomous private high schools, foreign-language high schools and international high schools” in March of 2025. These so-called “elite” schools will be converted into regular public high schools, “all at once,” according to Education Minister Yoo Eun-hae. This move will affect around 44,000 students in 79 schools, starting with students currently in fourth grade.

The Korean educational system is considered a powerhouse globally, albeit one plagued by real systemic issues. By some metrics, it is the most highly educated society in the entire world, with 70% of 24 to 35 year olds possessing some level of tertiary education, and 92% of students opting to attend (non-mandatory) high schools. Additionally, South Korean students perform extraordinarily well on standardized tests; they reliably score at or near the very top of international standardized tests, such as the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA).

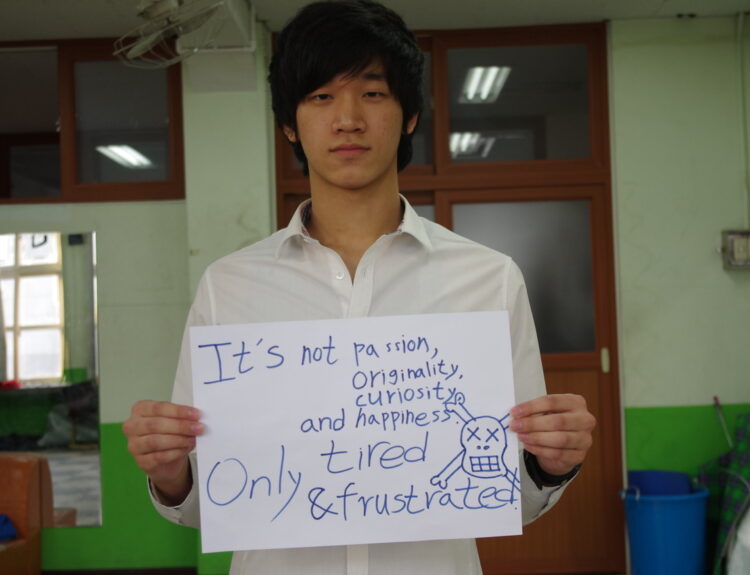

However, this educational system bears its own costs. Chief among these is the grueling system described by Professor David Calonge as “very stressful, authoritarian, brutally competitive and meritocratic…emphasizing high pressure and high performance.” Students spend dozens of hours per week in so-called “cram schools”, known in Korean as hagwon, studying everything from English and math to computer programming and music. It is an unrelenting race to get an edge over one’s peers.

Although only 4% of Korean high schoolers are enrolled in elite high schools, they have access to a different curriculum. As a result, the Korean students in these institutions are selected according to very different standards, unlike public schools, and competition to get in can be fierce. Additionally, they have far better chances than the average student of being accepted by prestigious universities abroad, or by one of the top three institutions: Seoul National University, Korea University, or Yonsei University (collectively and evocatively referred to as the “SKY-universities”). This makes entry into an elite high school its own grinding competition among middle school students, something that helps support the $1.6 billion dollar hagwon industry.

Unfortunately, the psychological toll of this ceaseless competition is only sharpened by high youth unemployment rates — a remarkable 11.2 percent of Korean youth is unemployed, something not seen since the Asian Financial crisis 22 years ago. The ever-increasing numbers of competitors, and the relatively static number of prestigious jobs, have combined to create a veritable pressure cooker for young Koreans. Suicide is now the leading cause of death among teenage Koreans, in a country with the highest rate of suicides in the OECD.

The Korean government has committed to an ambitious plan to overhaul many of the most problematic elements of the educational system. This includes a 2.2 trillion won ($1.8 billion USD) increase in funding for public schools, an attempt to cut down on holistic acceptance among universities, and of course, the aforementioned ban on elite high schools. These measures are intended to increase equal access to educational resources and make the overall system fairer, not just for the children of elites, but for the average student as well.

Unfortunately, many of these policy solutions could breed more problems. An increase in funding is of course always welcome, but unless it is paired with systemic changes, it seems unlikely to make much difference to the lived experiences of Korea’s four million high school students. And, regrettably, it does not seem like the broader changes are likely to help.

First, a move away from holistic acceptance in universities may help decrease the importance of extracurricular achievements, internships, and contests. These are areas where the children of wealthy families have the resources to compete in ways that poorer students simply cannot match. However, a move away from holistic acceptance is necessarily an increase in the importance of standardized tests. Korean schools already place a remarkable amount of pressure on students to pass the College Scholastic Ability Tests (CSAT), also known as the Suneung. This one test, administered once a year, determines much of the course of each student’s academic and professional life. On the day of the test, streets are closed and air traffic rerouted so as not to disturb the test takers. Of course, more focus on the Suneung is only likely to intensify the stress high school students feel and increase the importance of high level tutors and elite hagwons to wealthy students.

Additionally, the transition of elite schools to regular public schools, though undertaken for good reasons, will have other unintended consequences as well. Two teachers at one such international school, who asked to speak anonymously, pointed to several of these. First, international schools play an important role in Korean education, not just for Korean students but for the families of diplomats and other foreign workers that require English language instruction and prefer an International Baccalaureate (IB) system. “Our school operates under an understanding with the government, that we can only take a certain number of Korean students in … about 30% Korean students,” said one teacher. “I’m just wondering, at the end of the day, is that what they’re trying to take away, that they don’t want these [Korean] kids to come to these international schools.”

Another important role for these elite schools is as a test bed for new kinds of approaches to curriculum, especially those employing teaching styles more popular outside of Korea. Particularly for schools from poorer, more rural provinces far from Seoul, a movement towards fewer modalities of teaching may actually be harmful. “Something else that we have seen is …Korean public schools coming to our school to see how we teach, how we approach it,” reported one teacher. “Especially schools from poorer provinces, they are looking to change the way they educate, and they are coming to us to learn more about how to adapt other approaches.”

All in all, these reforms, though clearly meant to accomplish the noble goal of helping students, run a real risk of swamping any positive effects with unintended consequences. “I think it’s kind of a sweeping, top-down solution, which I don’t have a lot of hope for,” said another teacher. “But I guess we’ll find out.”

- Would Education Obsessed Korea Really Cut Elite Schools? - January 9, 2020

- Is Korean food going foreign? - November 12, 2019

- A Fragmented Future? Huawei and the Future of the Global Economy - June 13, 2019