How damming SEA’s largest river is hurting the region, and how a grassroots electricity movement could help

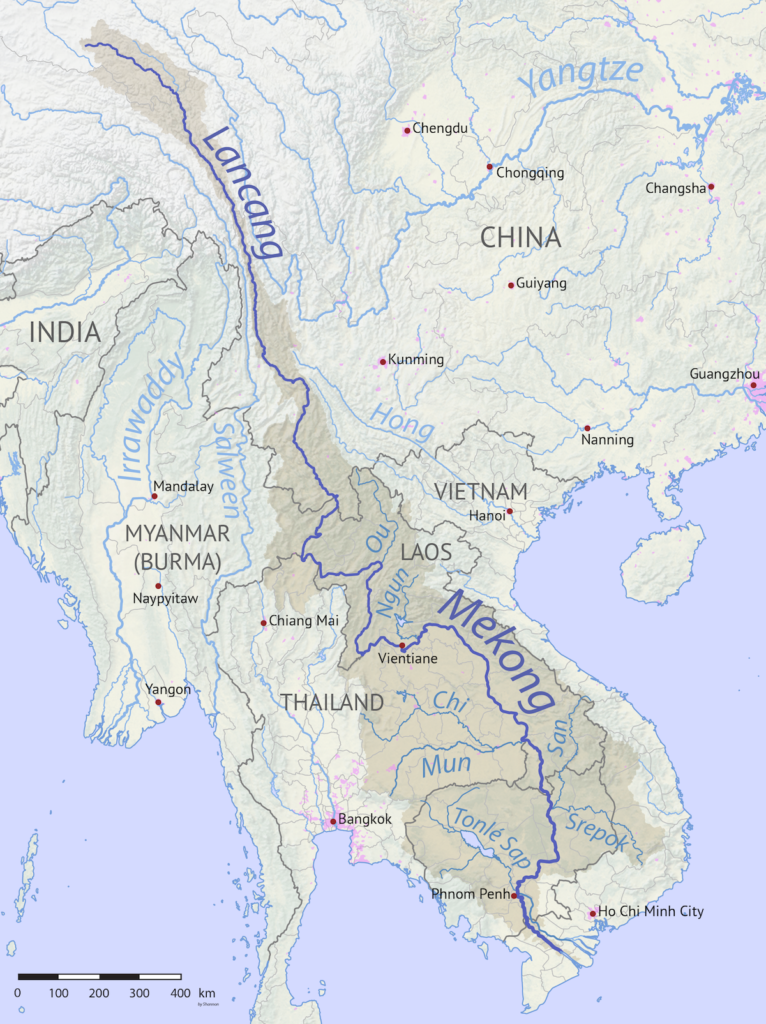

It begins on the Tibetan Plateau, where heavy monsoon rains some 17 million years ago formed the gorges that would one day fuel a mighty river. It then flows through southwest China, where the people of Yunnan province have washed their clothing, caught their fish and built vast rice farming communities for millennia, all without putting a dent in its flow. After that, the Mekong River begins a grand tour of Southeast Asia, hardly missing a country as it passes the Buddhist pagodas of Myanmar, delivers hydropower to Laos and Thailand, provides the world’s largest inland fishery to Cambodia, and finally meets the ocean via southern Vietnam.

The Mekong River is a life force for many countries in Southeast Asia

But rivers, like all of nature’s resources, have their limits. Under the weight of excessive damming in Laos, overfishing in Cambodia and global warming worldwide, the Mekong River is beginning to cry out. Or at least the people living along its banks are.

The nations of Southeast Asia (SEA), and Laos in particular are capitalizing on the Mekong as a source of cheap, renewable energy, building hundreds of large-scale dams in order to sell low-cost hydropower to China, Thailand and other neighboring countries.

And yet this summer, we saw the risks behind Laos’s goal to become “the battery of Southeast Asia.” In July 2018, after a typical bout of monsoon rains, a dam in southern Laos that was under construction broke open. The ensuing flood was devastating — it took hundreds of lives and left some 6,000 people homeless, forced to abandon their lives along a river they had called home for generations.

The dam collapse in Laos left hundreds dead. Photo: india.com

But it’s doubtful a disaster even of this magnitude will do much to change the Laotian government’s plans to build dam after dam along the Mekong River. A landlocked and mountainous country, Laos is among the poorest in Asia by GDP. The sale of hydropower to wealthier neighbors represents one of its largest sources of income, bringing in some $610 million from 2013-14. Laos has been relying on income from hydropower dams ever since the first large-scale project, the Theun-Hinboun, was completed back in 1981 and government officials were stunned to see foreign cash finally pouring into the backwater nation.

“When that happened it represented 5% of Laos’s GDP. They’d never seen a cash cow like that,” said Dr. Kim Geheb, a natural resources management specialist at the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), whose work now focuses on the Mekong. “They were so blown away by this easy cash, and that’s really what they then chased after.”

It’s rumored that before hydropower, Laos’s only source of foreign currency was from fly-over fees — money it collects from airline companies when they fly over its airspace.

The question is, how do you ask a poor country to forego its biggest profit machine, especially when hydropower technically counts as “renewable energy”? In 2016, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) joined other countries in signing the Paris Agreement, promising to lower emissions and reduce their impact on climate change. SEA nations are acutely aware of the effects of increasing temperatures. Rising water levels are expected to hit populations in places like the Mekong Delta in Vietnam especially hard, giving local governments reason to take the Paris Agreement seriously.

Geheb says there’s already plenty of anecdotal evidence of climate change along the Mekong. “Typhoons are much more regular and severe. The rainy season we’re seeing at the moment has been particularly bad, with lots of flooding.”

For its part, Laos is doing what it can to uphold the commitment it made in Paris. Dams do not create C02 or cause warming, and they are a vehicle of renewable energy — so long as the water keeps flowing, there is enough to power local cities and even sell the remainder for a handsome profit. In one stroke, Laos is solving two problems: creating a stable income for its struggling economy, and abiding by the Paris Agreement. But what looks like a perfect solution on paper is not going according to plan.

The risks go beyond just flooding. Excessive damming is hurting the Mekong River’s ecosystems and depleting the fish populations which the local people rely on in a way most urban dwellers can’t fully comprehend. The environmental damage caused by large-scale dams is so intense that even the world’s large development banks, such as the World Bank and ADB, are refusing to fund their development.

“For most development banks, if you propose such a large scale dam, in most cases they say no,” said Jung Tae-yong, professor of sustainable development at Yonsei University in Seoul. “Too much negative impact on the environment.”

Development banks are beginning to see the value in natural ecosystems like the Mekong River, but that doesn’t prevent the private sector from rolling in to grab up billion dollar projects. The dam that collapsed this July, a joint project by South Korea’s SK Engineering & Construction, a Thai electric company, and the Laotian government, was a $1 billion dollar project.

Many people rely on the river as a home and source of food

Laos’s government has already allowed 51 dams to be constructed and has 46 more in the pipeline, representing huge profits for construction companies, and the possibility of lifting Laos out of poverty.

But in their push to find their next cash cow, local governments and dam builders may have missed out on — or perhaps purposefully ignored — a grassroots movement that could change electricity in the nation, empowering the local people and giving them a new, renewable income stream.

Geheb notes a trend starting in Thailand that could very well spread to Laos, and has the potential to turn homes and small villages into power creators.

“Thailand is struggling with so-called ‘disruptive technologies,’ basically houses installing solar panels or putting little windmills up on their roof.” So far, the goal of government and electricity providers has been to monopolize power production. They produce the electricity, keep it under their control, and sell it back to the people. “But they’re losing their grip on production,” Geheb says of Thailand.

People across the region have been taming the river, now some feel it has been tamed too much

If things move in this direction, it could liberate local populations and lift them out of poverty, without the need for destructive dams that hurt local ecosystems and uproot entire communities.

“At the grassroots level, people want democratic power production. A significant part of their livelihood’s cost is paying for their power. If the difference is a cheap Chinese solar panel on their roof and you never have to face that cost again, and a couple of truck batteries you charge up during the day, it’s fairly attractive.”

When those communities create more power than they can use, they simply sell it back to the grid, creating an income for themselves.

Challenges would still exist. Solar power becomes useless at night, requiring a smart grid that can shift to another source when power supplies run low. Most places in SEA don’t have these grids yet, but it remains an option that governments will be under increasing pressure to consider.

While it may not sound like an attractive deal for governments and power providers, who would essentially be giving up their monopoly over the grid, Professor Jung thinks the shift is not only inevitable but a smart move for them.

“Small-scale hydro is now getting more and more popular,” he says, mentioning small hydro machines that would produce enough power to help a village handle simple farming functions like pumping water. “It’s changing. Otherwise, how is [the government] going to meet all these different types of demand? They have to change their minds. If they keep it central, it will actually be more expensive.”

This is something like the shift happening in California, where the Sunshine State’s governor has encouraged clean energy use by providing subsidies for solar panels and allowing users to sell excess energy back to the grid.

If introduced in Laos and other areas along the Mekong, these policies could lower the need for dam projects while providing power and an income to local people.

That solution may be a long way off. Understandably, governments are holding on to their control over the power grid and the vast income that comes with it, even when it goes against the country’s interests. While governments in Denmark and California are making plans for zero emissions, Vietnam has announced that it will increase its use of coal burning by 2030. They claim to have the technology needed to capture emissions, but to many, it looks like an effort by Vietnam Electricity (EVN) to keep their monopoly over the power grid.

Democratization of the power grid may be a hard sell in nations that are not themselves democracies, and where putting power — electric or otherwise — in the hands of the people goes against party rules. On the other hand, these countries also have recent memories of what happens when you deny a population its rights for too long.

“Revolution is within living memory,” said Geheb. “They know exactly what that means. So for the more authoritarian governments within the region, the question becomes, how far can we push our populations before they revolt.”

- Korea has boycotted Japanese beer. How will I round out a 4-pack of tall cans? - August 18, 2019

- A$AP Rocky is doomed to Swedish meatballs. Thankfully he’s well connected - July 22, 2019

- Trump and Kim are Helping Me Sleep at Night - July 10, 2019