Months into the protests of the Candlelight Movement brought about a change in a new administration and by the time it was spring of the following year, President Moon Jae-in was sworn into office. The expectations for the Moon administration was justifiably high and in his inauguration speech, the South Korean citizens seeked consolation from his words that promised to revitalize the nation into one worthy of its name: a great power of East Asia. Embedded within the vows that Moon pledged when he took office was a deep connection that was rooted in his parents’ background as North Korean refugees and a fervent hope to alter perspectives respecting inter-Korean relations. Moon’s initiative to change the inter-Korean rhetoric was very much evident in his message during the presidential campaign as he promised to “resolve the security crisis as soon as possible” and declared the issue to be of topmost priority by stating, “For peace on the Korean Peninsula, I will do everything that I can do.” However, little did he know back then that such desires would still remain one of his unresolved assignments even towards the end of his presidency and that his diplomatic approach would lead to a decline in the support for the issue across generations, especially that of the youth.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The Asian edition of Time Magazine, introduces President Moon on its cover and refers to him as ‘The Negotiator’ / Source: Time Magazine

President Moon, who was declared “The Negotiator” at the beginning of his presidential term, came forth with the goal to make a breakthrough in inter-Korean relations and announced on several occasions that Seoul has taken a backseat on the matter for far too long. His main focus was to take a “step-by-step, comprehensive approach” that would call for sanctions and talks, steering the path towards denuclearization and ultimately, reunification. Although ambitious, Moon has tried to break the status quo of previous conservative party leaders and proceeded on to reach out to North Korea time after time and also to coax the United States to get involved in the negotiations.

Ever since, the administration has faced negligible improvements only to be dumped with unrestrained failures and backlash. Moon held three summits with Kim Jong Un in the year of 2018 alone, crossed over the demarcation line which was hailed as a “historic moment” by the international community, and such events seemed to cause a ripple effect not just in areas related to politics but also in the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics, when the North and South Korean athletes marched under one united flag.

The Singapore Summit / Source: Kevin Lim (The Straits Times)

Trump was also brought on board for Moon’s plans and the 2018 Singapore summit presented the first-ever sitting American president to meet with a North Korean leader. With the support of the United States, one of the most active actors in international relations, the road to more effective talks with North Korea seemed acutely possible and soon enough, a summit in Hanoi and another meeting in Panmunjom were welcomed by North Korea and the U.S. in 2019.

However, this rocky fairytale was short-lived. When Pyongyang decided that the talks weren’t playing in its favor, the state raised tensions by warning Washington of its displeasure and eventually disregarded its negotiations with the U.S. and South Korea altogether by following through with the launch of a series of short-range missiles and experimented with new forms of threat such as the 600m multiple rocket launcher system and a submarine-launched ballistic missile, the Pukkuksong-3. North Korea also blew up a joint liaison office located in the Kaesong area to depict its position and disinterest in dialogue. The momentum built by the leaders of North and South Korea was crushed and when it came down to it, it seemed as though every step forward was met with a trigger that pushed the progress two steps back.

The 2030 Generation

Along with many other reasons, President Moon’s empty persistence has exhausted the South Korean citizens. Although attitudes on economic assistance and humanitarian aid towards North Korea have always been negative as a result of the emotional baggage triggered by the Korean War, the younger generations have voiced out a strikingly evident disapproval over Moon’s blind eye and extended olive branch.

It would seem logical however, that the elderly have a more closed approach toward reaching out to North Korea because of their direct and firsthand connection to the wartime period. However, it has been observed that the South Korean youth share a far more critical perception of offering aid and perceive North Korea as more of a threat than do the older generations.

In the case of the event when the government proposed the formation of a unified inter-Korean women’s hockey team, the South Korean youth depicted condemnation. Statistically speaking, in a survey carried out by the Korean Council for Reconciliation and Cooperation, a staggering percentage of 58.7 expressed opposition to a unified hockey team. As one Blue House source stated, “We thought the public would understand and support the forming of a unified team, but there turned out to be major differences with the views of the ‘2030 generation’ [young people in their 20s and 30s]…We failed to gauge their feelings accurately.”

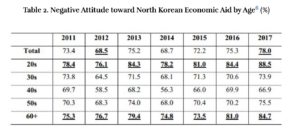

Source: Asan Institute for Policy Studies

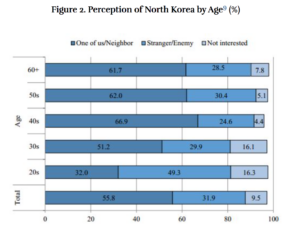

Moreover, as illustrated in the table above, 88.5% of the people in their 20s have expressed disfavor toward North Korean economic aid. These numbers are staggering when compared to the people in the 40s, 50s, and 60s which show percentages of 66.9%, 75.5%, and 84.7% respectively. It is also evident that throughout all age groups, the percentages have gone up over the years and this signifies that the issue of inter-Korean relations isn’t being discerned in a good light as Moon had hoped. In a similar vein and as seen in the figure below, the percentages of people who perceive North Koreans as “one of us/neighbors” were much more prominent in the age-groups of the 40s, 50s, and the 60s than those in their 20s. In fact, the youth answered that they view North Koreans as “strangers/enemies” rather than those of their own descent.

Source: Asan Institute for Policy Studies

Is Reunification Really Necessary?

Then, the question comes down to if reunification really is necessary at this point in time.

Experts have noted that the rapid transformation of industrialization and modernization that South Korea went through offers an explanation for the younger generation living through a narrative completely detached from that of the previous generation. Steven Denney, a graduate fellow at the Asian Institute, conveyed that “Those in their 20s and 30s are less likely to see North Korea as part of the same nation and are more likely to show even hostile views towards the North,” and even brought the issue further on to state that “Many young South Koreans today have come of age during North Korea’s nuclear push. They see international condemnation and sanctions against a country which regularly threatens to turn their capital city into a sea of fire.” Similarly, Professor Sang-yoon Ma of Catholic University of Korea has indicated that the Korean youth considers foreigners that are familiar with Korea much more of a closer entity than North Korea.

This negative response from the youth signifies and proves that the younger generation realize that reunification will come at price and they are the ones who will have to pay. The reason for opinions against reunification and any more progress on inter-Korean relations is triggered by a heavy responsibility rather than an indifference. Much of the younger generation perceive North Korea to be a grave and massive threat to political security, which explains why they are against the idea of homogeneity. In this regard, Moon’s attempt in trying to portray the North and the South as “One Korea” using nationalistic sentiments cannot be deemed realistic as everything from the political system to the social values differ vastly. If reunited, the cohort that will have to experience the mending of such differences for a longer period of time and with much more consequences is the younger generation. Bearing this in mind, it is difficult to continue to push for the hopes of Moon and a majority of the older generations, and for such hopes to replace the passivity felt by the younger generations in regards to this matter. This, of course, does not imply that the two Koreas need to be on hostile terms but rather that unification does not have to be and may not have been the conclusive answer after all.

The Forgotten War

After being at war from June 25, 1950 to June 27, 1953, the Korean War ultimately ended in armistice and the North and the South have remained divided up to this day. Despite the fact that nearly 5 million soldiers and civilians lost their lives due to the conflict, it is often referred to as the “Forgotten War” for the lack of attention that it received from the international community in comparison to other notorious periods in history. However, while it may be deemed as the “Forgotten War”, the impact and repercussions that the war left behind in history, the people, and the deeply-rooted resentment between the divided nations are everlasting even up to this day.

As the field of politics is met with a paradigm shift in generations, the younger generations are now in charge to decide what the ending of the Korean War could entail but the youth refuse to carry on the unfinished assignment of Moon. As time for Moon is slowly running out, the lone legacy that he is leaving behind is proof that it is difficult to rewrite history.

- Not in Education, Employment, and Training - October 7, 2022

- Unification Of The Two Koreas: An Economic Approach - January 26, 2022

- Mission Impossible?: Refugees Seeking The Korean Dream - November 24, 2021