Myanmar nun pleads with police to stop bloodshed. Image via Mashable SE Asia.

This article was originally posted on The Peninsula Report and has been reposted with permission.

By: Joon Ha Park

As Myanmar currently fights for democracy, it’s worth taking a look back in time to a similar period in South Korea’s history. Similar to what the people of Myanmar are going through now, South Koreans also had their own fight for democracy against a military dictatorship some forty years ago. Although things may look bleak, the South Korean case shows that protests are indeed very powerful and that even a military-run government cannot stop the will of an entire nation. The situation right now is bad, but things can get better.

#WhatsHappeninginMyanmar

On February 1, General Min Aung Hlaing and Myanmar’s army (known as the “Tatmadaw”) seized control of the country’s elected government in a staged coup d’état, justifying their actions by using the alleged election fraud by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) as their reason. Ms. Suu Kyi and other prominent figures of government and other democratic activists were arrested as the leaders of the coup declared a state of emergency.

Ms. Suu Kyi’s NLD recorded a landslide victory in last November’s general elections, securing the democratic legitimacy to lead the country for the next five years. The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development party secured only 33 seats in comparison. While the election commission has denied any accusation of fraud, the military has persistently claimed to have found over 8 million cases of election fraud.

The junta has been quick to suppress any opposition. In early March, police raided a local news outlet, stormed several hospitals, attacked ambulances and healthcare workers. Airports were closed, the internet was shut down and a country that had been a democracy only a month before was once again a military regime. The Tamatdaw’s coup has been followed by mass protests, with citizens young and old holding up the three-finger hand gesture, a symbol of resistance and defiance against the brutal crackdown enforced by the military.

Security forces and army troopers in Myanmar have turned their guns and weapons against their own people, effectively disparaging the basic military principle of defending the livelihoods of the citizens that they swore to protect.

To this day, Myanmar has lost more than 400 people from the senseless military crackdown and over 3,000 arrests have been made. Many have either been shot in the head by snipers or randomly shot by soldiers. Last Saturday saw 114 people killed on the bloodiest day since the February 1st coup. On the Tuesday of the same week, a seven-year-old girl was shot and killed by security forces in her home as she sat on her father’s lap. A 19-year old woman known to many as Angel was shot dead while wearing a shirt that printed the phrase ‘Everything will be OK’. To make matters worse, her grave was disturbed by the authorities, where it was found to have been closed with a fresh coat of cement after being dug up for inspection.

Angel, 19, moments before her death, wearing the ‘Everything will be OK’ shirt. Image via Reuters.

Outrage and chaos spread throughout the nation, where police brutality and the readiness to die have been key elements of the average protestor’s struggle. The chance of dying is so real that many of these protestors write messages and their blood type on their arms, in case of possible death or injury.

Parallels with South Korea’s past

As South Koreans took to their news feeds and their TV screens, the images of Myanmar’s struggle sparked memories of similar events that took place in their own country not too long ago.

South Korea is no stranger to pro-democracy struggles. Every day, Seoul’s citizens make their morning commute by walking on pavements that used to be sites of protest or where someone was arrested. From the April 19th Revolution in 1960 to the Candlelight Demonstrations in 2016 and 2017, South Koreans have consistently fought to defend one basic democratic principle: the power comes from and remains with the people.

Likewise, coups have lined key chapters in today’s history textbooks, as the country experienced two presidencies as a result of a coup d’état, both totaling over 20 years of dictatorial rule.

In late October 1979, President Park Chung-hee, a dictator who came to power through his own coup d’état in 1961, was assassinated by one of his closest aides, ending more than 16 years of autocratic rule in the country. As South Koreans basked in this new-found period of political liberation, a group of military officials ended any dreams of democracy in the name of “national security”.

Just months after Park’s assassination, General Chun Doo-hwan and his military group (known as Hanahoe) took power through another coup. Shortly after the coup’s success, Chun’s military junta seized control of the government, restoring many of the restrictions from Park’s regime and arresting prominent democratic leaders Kim Dae-jung and Kim Young-sam.

As Chun’s control over government strengthened, protests against Chun’s military junta spread across the country. On May 17th, Chun declared martial law and the junta’s eyes turned to Gwangju, a city located in the southwestern region of the peninsula, which had been a proactive site for protest against the Park regime and Chun’s new intervention. Chun and his junta had sent combat-trained paratroopers to Gwangju, justifying this by classifying the democratization movement as a communist riot.

A paratrooper beats a civilian in Gwangju, May 1980. Image via South China Morning Post.

South Korea in the 1980s

After Chun’s coup and the declaration of martial law, one of the darkest chapters in modern Korean history began. A week of senseless killing and purging commenced. Men, women, and children were shot and beaten. A pregnant woman waiting for her husband was shot dead by a sniper. Children became orphans, wives became widows and parents wept holding coffins containing their children.

Ammunition that was meant for the defense of the Korean people ended up killing over 150 South Koreans. According to the May 18 Memorial Foundation, over 4,000 civilians were wounded, 154 were killed and 74 were recorded as missing. In order to contain the news of the terrors in Gwangju, phone lines were cut and broadcasting stations around the city were surveilled and censored, with every news article keeping in line with the junta’s stance which labeled civilian protestors as communist rioters.

Shortly after the massacre, Chun took his position as president, once again stalling South Korea’s democratization process. Soon after his Presidency began, students and activists were arrested and tortured at the infamous Namyeong-dong building, known to many at the time as a site of brutal interrogation.

In January 1987, South Koreans were baffled to read of the news of a student’s death at Namyeong-dong. 21-year-old Seoul National University student Park Jong-Chul had died by suffocation. As the policemen dunked his head in a tub of water, his throat was crushed by the tub’s rim. When the authorities were asked the reason for his untimely death, they simply responded by saying that he died of shock. South Koreans were furious. While students had been the main activists in the struggle against Chun’s regime, parents and adults came onto the streets, shouting “What if it was my child?”

Seoul National University students holding a silent protest while holding the portrait of Park Jong-Chul, January 1987. Image via Nanummunhwa.

While the authorities passed it on as incidental, more and more mysterious disappearances of activists and students were covered by the media. On April 13th, Chun appeared on television to deliver an address that signified his decision to pass on his leadership to his self-appointed heir, effectively signaling an extension of dictatorial rule.

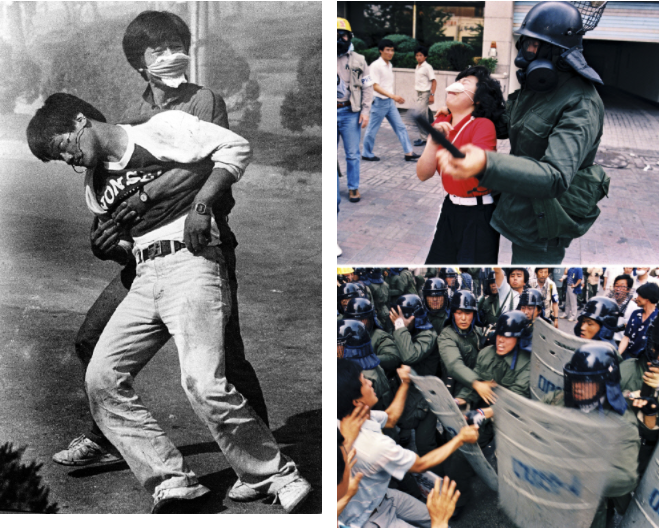

In June 1987, Yonsei University student Lee Han-yeol was shot on the back of his head by a tear gas canister. The image of his unconscious body being carried to safety by a colleague (below) is quoted as being one of the most iconic images of South Korea’s democratic struggle.

Lee Han-yeol (front) being carried away by Lee Jong-chang (back), a fellow student at Yonsei University, June 1987 (Left Photo). The June Struggle, 1987 (Right Photo). Images via Yonhap News and Kyunghyang Shinmun.

Restoring democracy

With Chun’s statement and Lee’s fatal injury, South Koreans young and old came to the streets in a nationwide movement to restore the democratic vote and topple the dictatorial regime. After the protests raged on, Chun’s government announced that they would restore the democratic vote on June 29th.

However, even after South Koreans re-established their democracy, the main perpetrators were still in positions of power. Due to a failure of either Kim Dae-jung or Kim Young-sam to emerge as a single unified candidate for the democratic movement, the people’s votes ended up being scattered and Roh Tae-woo was elected President. Roh was a significant member of Chun’s cabinet and one of the main military leaders who aided Chun’s national security campaign. It was not until 1992 when South Korea had its first civilian President in Kim Young-sam. Shortly after, both Chun and Roh were arrested on charges of corruption and sentenced to death until they were pardoned by Kim Dae-jung in 1997. To this day, both Chun and Roh still deny any involvement in the massacre of civilians in Gwangju.

Despite the martial law in Yangon and Mandalay, Myanmar’s fight still rages on. As protests have resulted in numerous casualties and arrests, the people of Myanmar have turned to another option of protest. A boycott of companies linked to the military junta is now in full motion, with many corner stores and supermarkets taking Tamatdaw-linked products off their shelves. Many civil servants have also taken leave, striking in resistance to a government that is not theirs. This resistance, led by a boycott and a series of planned strikes, is being practiced enforcing economic pressure towards the military junta.

Just as South Korea was able to restore democracy in the 80s, the same is possible for the people of Myanmar. People from all walks of life are voicing their protest against the military junta and have proven just how determined–even ready to die–they are, to save their country from military dictatorship.

Throughout this all, it’s worth remembering one key phrase:

“Everything will be OK”.

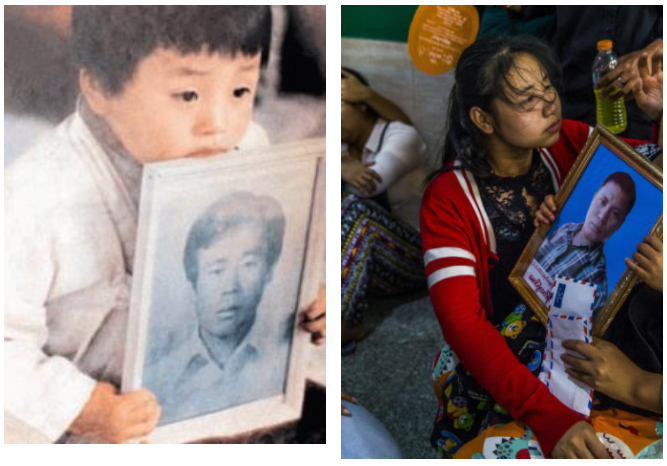

(Left photo) A boy in Gwangju holds his father’s funeral portrait, May 1980. (Right photo) A girl in Myanmar is comforted by her parents as she cries holding her father’s portrait, March 2021. Images via Joongang Ilbo and Bangkok Post.

- “I Love My Body”: Hwasa and Female Empowerment in K-Pop and Korean Society - May 6, 2025

- English Fever in South Korea - February 24, 2025

- South Korea’s Medical School Expansion – Cure Worse than the Disease? - October 20, 2024