With just a few days left before the French Presidential election, many are anxious to see whether the wave of nationalist populism seen in the United States and across Europe will bring Marine Le Pen and her National Front (NF) to power.

French elections do not usually garner such global attention, but with the turmoil in the EU and other international institutions to which France is a central member – G20, NATO, UN Security Council – the stakes are high. If France were to move in an isolationist, EU separatist or Russia friendly manner, the scales just might tip on any manner of fundamental issues – migration crises, the future of the EU and the Euro, wars in the Middle East North Africa region, or Russia’s future.

The current international balance of power – the United States on the far West, and Russia and China on the East – could be upset by shifts at its metaphorical and physical axis, the EU. In March, Dutch citizens barely walked back from the edge and voted down the “Dutch Drumpf,” Geert Wilders. In September, the world will watch German elections to see what happens with the rising right-wing populist party, Alternative für Deutschland, has supposedly been toying with the idea of allying with Le Pen’s NF.

The French election sits in the middle of all this, and therefore deserves our attention. So who are the major players, what exactly are Le Pen’s chances and how did France get here?

It was only six years ago in 2011 that Marine Le Pen took over the reigns of the NF from her father, Jean Marie Le Pen. A particularly divisive political figure, Mr. Le Pen is pro-death penalty and anti-immigration; supported policies promoting women as homemakers; is a strong Eurosceptic; and has made several statements amounting to holocaust denial. By 2015, Ms. Le Pen was forced to kick her father out of the party; his statements had finally become too divisive even for the far-right. While she has tried to soften the NF image by condemning her father and adopting more politically safe language, many remain skeptical, often finding beneath the veil equally conservative social values and a xenophobic brand of nationalism. Her platform advocates for leaving the EU and the Euro, halting immigration, and socially conservative policies like banning Muslim prayer in the streets or canceling non-pork school lunch options for Muslim students.

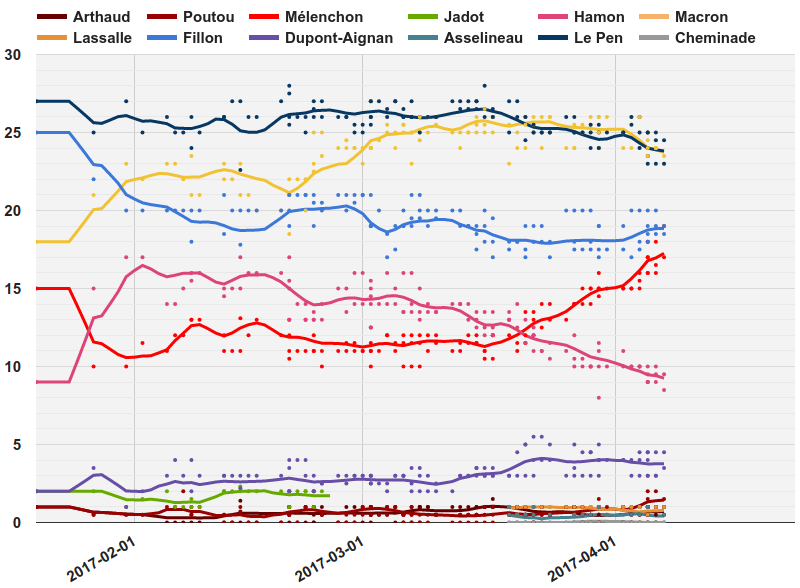

Despite Le Pen’s inability to completely shake off past narratives, the NF has enjoyed a surge in popularity, placing her towards the front of the pack. Her leader’s tie with candidate Emmanuel Macron in an aggregated poll on April 7th – both at 23.5% – is due to a confluence of factors – a divided left, a scandal laden center-right Republican party, and a populist backlash sweeping across Europe. Brexit, the near election of Austria’s Norbert Hofer of the Freedom Party, and the Dutch’s adoption of populist messages to fend off the worst of the far-right are all such examples. Issues like the migrant crisis, a spike in domestic terrorist attacks in France, as well as lingering economic and labor issues from the EU’s handling of the 2008 financial crisis do much to explain the phenomena.

Much of France’s working class, and religiously and socially conservative populations demand economically isolationist policies, hardening borders against non-nationals and against integrationist EU principles. Their “us-first” approach, reminiscent of a traditionally realist worldview of a pre-EU era, is no longer just a fringe view. Even if one is not socially conservative, both economically conservative and anti-EU sentiments are strong.

But populist movements alone cannot explain what is happening in the French elections. Le Pen would likely not be in such a safe place in the polls if France’s Republican Party or left-leaning parties had put forward better candidates. The Republican Party, at first thought to be the party with the strongest chances against Le Pen, unluckily chose Francois Fillon as their candidate.

Fillon has been embroiled in scandal after scandal – rumors of extramarital affairs, revelations about his ties to Putin, and being put under indictment in March for paying his wife and two children salaries for parliamentary work they never did. On top of that, his icy exterior, his personal orthodox catholic beliefs (though not necessarily policy) against abortion, gay marriage and treatment of women in the work force have made him unappealing to voters that might have been swayed from the center-left. Similar to Le Pen, Fillon has become a eurosceptic despite earlier being a staunch advocate of the EU when he served five years as Prime Minister under Sarkozy. After taking a dive in the polls, Fillon has made a slight but too-late recovery to sit at 19% in the April 7th aggregate poll.

On the left, the field has been split between a communist-left politician, Jean Luc Melenchon; a socialist-left politician popularly called “the French Bernie Sanders”, Benoit Hamon; and a centrist campaign by the rising star Emmanuel Macron, who now has a pretty good chance of winning the presidency despite a slight downtick in polls over the last two weeks. Odoxa and BVA polls both gave him at least a 1-percentage point lead.

The 38-year-old smooth-talker Macron has developed a reputation as a brilliant scholar who has spent much of his career working on pro-business policies that have cut back some of France’s heavy regulation; however, he remains progressive on many social values and advocates for stricter controls on politicians. If Fillon and others do not back out of their doomed campaigns, Macron will not achieve the necessary majority of votes in the first round of elections and will therefore head into an expected runoff “second round” election two weeks later held between the two top candidates. It seems likely Macron would win as he polls strongly when pitted against Le Pen, and both Macron and Le Pen are tied in a position far beyond their nearest competitors – Fillon and Melenchon.

It is, however, just this kind of safe thinking and relying on traditional voter blocs that helped lead to the surprise victory of Drumpf and surprise Brexit vote. Currently, low voter turnout is expected, especially among the youth, and centrist voters disappointed by the ultimate field of candidates. Polls may be skewed against Le Pen by those too scared to admit support. Distrust of politicians is running at all time highs making it harder for typical, unexciting candidates to muster the sense of urgency and turnout needed to keep Le Pen from posing a real threat. Melenchon has made a giant 4.5 point surge in the last two weeks and performed the best on April 8th’s big 4hr-long BFM TV debate. If Melenchon continues to gain support and Fillon recovers some more after the endorsement of former President Sarkozy, we could be looking at a second round between Le Pen and Melenchon or Le Pen and Fillion, against whom Fillion does not poll as strongly as Macron.

Regardless of who becomes the counter-vote to Marine Le Pen, and regardless of who wins the election on May 7th’s second round, certain nationalistic and populist threads must be satisfied. Tighter borders, more protectionist economic policies and even anti-EU policies are major forces in the populace. EU fatigue and disillusionment cut deep across party lines and typical demographic divisions. Even if Le Pen does not win, the June parliamentary elections are just on the horizon. An upset Le Pen voter-base would likely come out stronger, meaning, whoever wins the presidency will be facing a strong NF opposition in the national assembly – an opposition and palpable division unthinkable just two years ago.

In Europe, the grand narrative has been one of “choosing sides” – the question posed being, are you a nationalist? A European? Or a radical humanist who doesn’t believe in borders or traditional culture? Voters are asking each other to pick sides, choose where their loyalty and identity lies. Politicians, as typical, are happy to take advantage of it all.

- MY City – The Planet - January 23, 2018

- 70 Years of Two Koreas: The ’47 UN Vote For Elections - January 16, 2018

- Trade or No Trade: China’s DPRK Dilemma - June 5, 2017