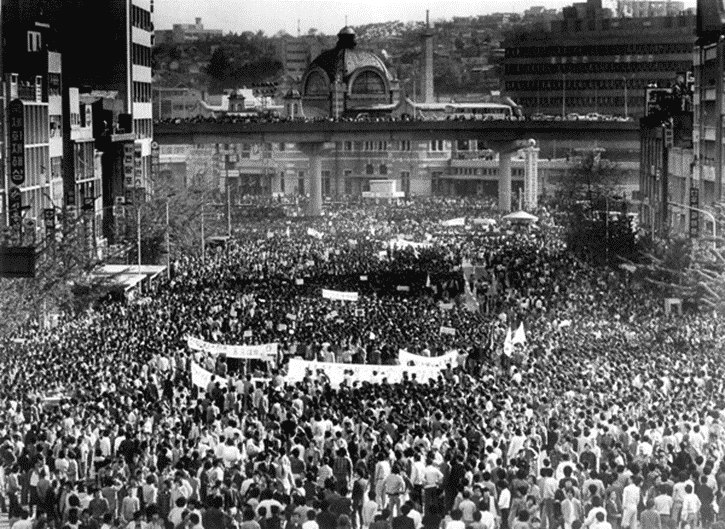

As the crowds gathered in Gwanghwamun Square in central Seoul in front of South Korea’s presidential residence, the Blue House, their voices rang out in unity for change. After persistent protests, the president gave in to their demands and decided to relinquish the position. This scene may seem familiar to younger people in Korea. Although one may think this describes the 2016 candlelight protests that eventually brought down the former President Park Geun-hye and ushered in a new era of Korean politics, that scene actually describes events in 1987, when the masses demanded an end to autocratic rule in favor of a democratic government.

The timing was particularly significant as Seoul was preparing to host the 1988 Summer Olympic Games, which countries vie to host as a chance to earn prestige in the international spotlight. The 1988 Games were seen as a major factor for South Korea’s then military president, Chun Doo-hwan, to acquiesce to the protesters’ demands and implement a direct election system in South Korea, instead of using violence to suppress the civilians, such as the violent crackdown of student protesters in Gwangju eight years earlier. Any footage of a military crackdown just a few months before the Olympics, one of the ultimate symbols of international peace, would have been disastrous for the South Korean government. In the end, democracy prevailed, and the world remembers Seoul as a successful host.

Thirty years later, South Korea hosted the Olympics again, the XXIIV Winter Olympiad in Pyeongchang, and the changes to the country are more than just political. In the past three decades, the country has made great economic and diplomatic strides as well. For two weeks once again, the world watched as South Korea took center stage and thrived. If the ‘88 Summer Games was an opportunity for South Korea to show the world it had arrived as a developed nation, the 2018 Winter Games reaffirmed its place as a world-class technological power and serious player in regional politics.

Of course, regional politics nearly always involve the activity of North Korea. Just as in 2018, North Korea featured prominently in the run up to the Seoul ’88 Games. Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s founder and grandfather of its current leader, Kim Jong Un, was upset that the International Olympic Committee denied his request for a shared Olympics. He also recognized that Pyongyang’s significance in the international community was dwindling. The economic gap with the capitalist South continued to widen, and recognizing this disparity, North Korea’s two most powerful regional partners, China and the Soviet Union (soon to be Russia after its collapse), began to take their investments to greener economic pastures of the South. Backed into a proverbial corner, Kim decided to lash out by wreaking as much havoc as possible before the Games started. In late 1987, two North Korean agents, in order to “create chaos” on the eve of the Olympics, blew up a South Korean airliner, killing all 115 on board.

The scare tactics failed, however, and South Korea was a successful host. Thirty years on, the peninsula is still divided, and the economic gap between the two Koreas has grown exponentially. Like a finely tuned sports car racing against a unicycle, South Korea has left its cousins in the North in a figurative cloud of industrialization dust.

This enormous wealth disparity was a part of current South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s vision for North Korean rapprochement, using the Olympics as his path to Pyongyang. For months, he emphasized his desire to turn the Pyeongchang Olympics into the “Peace Olympics” by extending an invitation to North Korea to participate. Pyongyang rebuffed all communication, and in Olympic deja vu, tensions surrounding the Games in late 2017 were mounting. Finally, North Korea responded through the form of Kim Jong Un’s New Year’s speech, and its obstinate leadership decided to participate in the Olympics instead of trying to sabotage them. Along with 24 athletes, it sent a brigade of cheerleaders as well as high-level officials for talks with their counterparts in the South.

These talks led to a South Korean special envoy visiting Pyongyang upon the conclusion of the Games, where its members dined with Kim Jong Un, his first known contact with South Koreans. They discussed an inter-Korean summit and a possible meeting with the American president as well, a major diplomatic breakthrough. Seoul did what Beijing and Washington were unable to: get through to the reclusive North Korean leader.

On the economic front, the engine that drove South Korea into the echelon of wealthy nations is still running, and the Olympics has played its own role in South Korean development. In 1988, South Korea’s GDP per capita was about 4,700 USD. Fast forward to 2016, the most recent year of statistics, and it was 27,500 USD. The Seoul ’88 Olympics helped breathe economic life into the mostly underdeveloped area around Olympic Park. That area, Jamsil, is now one of the ritziest parts of the city with its swanky lounges, high-rise apartments, and luxury shopping centers. Similarly, due to the location of the 2018 Winter Games in Pyeongchang, a few hours due east of Seoul, the government constructed a much needed high-speed train connecting the capital to the mountains and beaches of Gangwon Province. Patrons of the XXIIV Winter Olympiad also got to witness one of South Korea’s most known commodities, its technological prowess. The opening and closing ceremonies, which the author witnessed first hand, were spectacular shows filled with lasers, futuristic performances, and breathtaking fireworks that had its viewers in the stadium and on TV raving.

The legacies from each Olympic Games will be different. The 1988 Summer Games was about a newly industrialized nation ready to show itself to the world, and subsequent domestic political progress. In 2018, South Korea showed that its political institutions are holding strong. More than anything, the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics highlighted the important role South Korea plays in the international community. The trajectory of the country of the last thirty years has been an upward one, and if these past Games are any indication, South Korea will continue to rise.

- Kansas City: World War I’s Final Resting Place in America - November 9, 2018

- Moon Jae-in’s Elusive Peace - September 7, 2018

- Japan’s Diplomatic Vanishing Act - June 8, 2018