In 1990 Naomi Wolf published “The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women” to a polarized reception. The author argued that the social power of women has increased, they have a stronger impact on society, have access to good education, and enjoy rights that their female ancestors could have only dreamt of.

However, if you look at the situation closer you can see that this isn’t the end of the story. Even though women have broken through many legal and material hindrances, and have more money, power, and recognition than ever before, how we women feel about ourselves physically maybe even worse than before. The pressure to meet unrealistic beauty standards has also grown stronger, and, what is more, omnipresent and powerful media and advertising serve to propagandize that message.

The book was published 30 years ago. Has anything changed since then? Have we moved from artificial beauty standards to another perception of physical attractiveness? The answer could be yes and no at the same time. Yes, in 2020 we cherish diversity and understand its importance; we value a healthy-looking body over being extremely underweight, we advocate for doing sport, being active and living healthy lifestyles.

But on the other hand, the same media that might advocate all of the above is also unleashing the opposite content. Instagram influencers, of whom 4 in 5 are women, are getting more and more followers who are trying to live the same life or at least look like their favorite influencer; this provokes an increase in plastic surgeries and other cosmetic procedures; beauty content videos on YouTube are generating billions of views. On YouTube, in 2018 they constituted more than a third of views, and reviews and tutorials bring millions of dollars to their creators.

South Korean Beauty Market: A Rising Giant.

The beauty industry and cosmetics markets are the favorites of international business as well, especially the South Korean market. K-beauty exports have grown from $1 billion in 2012 to $2,64 billion in 2018, according to Korean Customs Service, due to the rise of Hallyu wave (more commonly known as K-wave – an increase in the global popularity of Korean culture and products). K-wave and Korea’s rapid development have brought about a change in society’s attitude towards beauty in Korea. With “Idols” and K-pop bands appearing, the understanding of who is a beautiful person has changed significantly. They are not just stars or celebrities, they are “idols”, and millions of fans now around the world are falling not only for catchy lyrics.

The K-pop industry is about more than just music, it is also about appearance, an image that is emblematic of unrealistic beauty standards. Thus, the standard of a beautiful woman, in particular, has narrowed down to having a small face with chiseled facial features, vibrant lips, and noticeable eyes. The skin of a “beautiful” Korean woman should be bright and not touched with suntan. A Korean woman’s beauty regimen may include from 10 to 18 steps skincare routine and up to 10 products to make the skin flawless and like what girls and women see every day in commercials, magazines and drama series – the perfect faces of drama actresses, singers, and models; but made only with great effort by a professional makeup artist or surgeon.

The South Korean beauty industry thrives by imposing social conformity as well as perpetually unreachable beauty standards for women. Revenue in the Beauty & Personal Care market reaches up to US$ 11.7 billion this year with Skin Care as the largest segment with a volume of US$7,102 million in 2020. Suyong (name changed), a Korean student from Yonsei University points out, “In the early 2000s, cosmetics shops called ‘road shops’ started their businesses, and the Korean beauty market has grown explosively.

I think the main factors for the successful K-beauty industry are low prices, a variety of brands and products, and high accessibility. Due to the high access to cosmetic shops, women were forced to be more exposed to their advertisements and products, and they would have had an unconscious influence on women’s aesthetics and beauty culture.”

Women’s Beauty and South Korean Society

Beauty is a big issue in modern Korean society. This willingness of women to change themselves to fit Korean ideals of physical beauty works perfectly for those who want to benefit from women’s dependence on beauty standards – cosmetics producers, film and drama makers, music producers, and even employers. It is, however, no surprise in a country ranked 115 of 149 OECD countries on gender equality in 2018. In a wave of protest against societal beauty prejudice, more and more young women in South Korea have decided to join the so-called “Escape the Corset”, another feminist movement.

The campaign developed from the global #MeToo movement and aimed to cast off the rigid standards of beauty. Women who are a part of the movement are not wearing makeup, dress the way they feel comfortable and cut their hair in a bowl cut. Feminist movements are on the rise in Korea and are eager to make a change in the society where patriarchal way of life is still strong regardless of democratic and liberal innovations in the society. If older generations of women have brought younger ones to where they are now, the new generation of women raised up in prosperous and economically stable situations are trying to make Korea an even better place for women.

What women today are trying to fight is the perception of women as weaker and only capable of “feminine” roles in society. According to OECD data, South Korea ranked 30 out of 36 nations for women employment, and the World Bank statistics vividly shows the gap in gender representation in political institutions: women hold only 17% of seats in the parliament.

As another form of protest against societal prejudice, some women decided to give up on marriage and childbirth and joined a #NoMarriage movement. The lack of necessary policies for women to give birth to a child and, at the same time, be able to maintain a job discourages young women from getting married, or bearing and raising children. So the followers of the movement choose not to marry or have children and believe that being single and free from motherhood can bring them more opportunities and self-development than rather being a married woman.

The Beauty Marathon

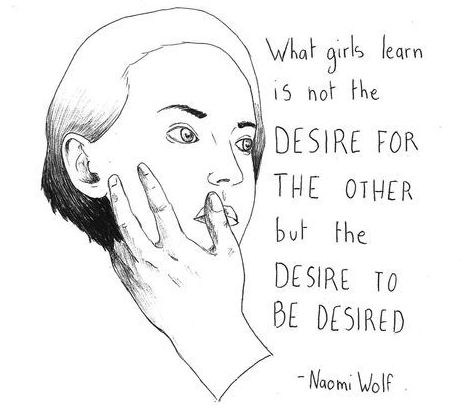

What we see nowadays and what women in Korean society feel today is that looking good and following the existing standards of beauty as well as being successful at work and having a nice family seems to be Mission Impossible. 30 years ago, Naomi Wolf wondered if this is women themselves who would join willingly into this never-ending marathon of chasing perfection and suffering from it believing the more beautiful they are, the more successful and happier they are with every side of their life, or whether it is society that creates the illusion of necessity for women to be all of this.

Though, if we ask ourselves, why we follow or decide not to follow beauty standards or certain expectations about “being beautiful”, for every young girl and woman, the answer and reasons for following them will be different. “I think the freedom to wear makeup is more important to me, more so than just wearing it. I think the ability to express myself or the ability to add a little something extra for my own personal reasons should be respected, not judged or criticized” says an international student from Yonsei GSIS. For her make-up or a desire to look beautiful is not a sacrifice, it is a way to express herself daily.

Suyong counteragrues, “Even if I feel that the importance of make-up is gradually decreasing, wearing make-up in itself is still important to me. Make-up eases some of my appearance complexes and makes me more confident and determined in my social life. It could be compared to the fact that I wear make-up in the dressing room to create my role as ‘social me’ before going onto the stage of ‘society’. Recognizing that make-up never changes my inner self, I still have the contradiction of wearing makeup”.

Young women in South Korea are trying to shake up long-accepted attitudes about cosmetics, plastic surgery and appearances. However, those who decide to defy societal norms and beauty standards are quite often met with misunderstanding from society and may become the targets of verbal abuse. These women are just some of those who decided to stand out and show their stance clearly to the society. Beauty and a pleasant appearance are nearly the most important assets for women to have in Korea to achieve success in any aspect – in career, marriage, status or influence etc.

To refuse to follow all existing standards means to build your own unique and, most of the time, unacceptable style of life in a society where conformity is at its high levels. “Escape the Corset” movement followers are just another non-indifferent people who care about the role and status of women in South Korea today but who refer just to one of the aspects of non-freedom.

Perhaps the question Naomi Wolf was wondering about 30 years ago – what drives women into following the imposed beauty standards, might be answered. I would say it is only when the freedom of choice to be or not to be perfectly beautiful in accordance with societal standards, the choice to follow or not the role and standard behavior of a “woman” is neither judged nor criticized but accepted as it is, that a change in society and its perception of women will be complete.

Legally and institutionally, in most countries around the world women are already equal to men and play as important a role and contribute to society as men: we have equal opportunities and equal rights under the law. However, what remains to be done in society is to move beyond theory, and start taking actions to make all these laws and ideas about gender equality and freedom to choose who you truly are come true. All the legislative and institutional triumphs that the 20th and 21st centuries have brought must become a solid platform for women to stand and speak up about the realities of their choices in their daily lives.

- The Quest for Perfection : Women and the Beauty Myth - April 2, 2020

- How can Human Rights Right Human Wrongs? - August 11, 2019

- Modern Marvels – what we get wrong about “getting” art - March 13, 2019