1980s Chinese cinema created the fifth generation of filmmakers, who were literally the fifth generation of graduates from the only film school in China, the Beijing Film Academy (BFA). This generation was reflective of China’s past since the Cultural Revolution and were the first to create films, which won international admiration for their sumptuous sets and flamboyant plots. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, a younger and more radical group of filmmakers came to the forefront; the sixth generation (i.e. the Urban Generation) – the newest graduates from the BFA. Their films were raw, gritty, and subversive. This article looks at the history of Chinese cinema from the 1980s fifth generation filmmakers, the birth of the sixth generation in 1990, and Suzhou River (2000) by Lou Ye as a representative film.

China: post-Mao

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a dark period for the cultural, intellectual and filmmaking society of China. Approximately 589 Chinese feature films, 883 foreign feature films, as well as thousands of documentaries, animations, science and education films were stored away and screenings were banned. Some professionals in the film industry were forced to the countryside, and others were incarcerated. The government viewed film as an effective medium of political propaganda so had held a tight rein on its production and distribution. After Mao’s passing in 1977, China was at the end of its communist rule and Cultural Revolution and at the beginning of its slow transition to a market economy. The Post-Mao Reform program was applied in 1978 and the 1980s were when changes were made to the agricultural sector and some to the service sector. Later, the 1990s saw immense transformations in the industrial, cultural, and political sectors.

Contemporary Chinese cinema can be traced to the end of 1978, when the Post-Mao Reform program (aka Policy of Reform and Opening) was initiated and its influence could be seen in the film industry in the early to mid 1980s. The new leader from 1978, Deng Xiaoping saw that the economy and society had suffered a lot during the Cultural Revolution, and in comparison to other Asian countries’ economies, Chinese people’s incomes were low. The solution was to create an open-door policy, to bring in foreign investment and technology, while staying committed to socialism. The film industry was one of the areas that was effected by this change.

It was a time when film was starting to be produced for entertainment, and not just political propaganda, with this era being heralded as one of the golden eras of Chinese cinema. 10 to 20 billion people were going to the cinema annually, which came to 10 to 20 times a year per person. The government’s transition to a market economy allowed those in the film industry to no longer be ruled by an iron fist, and instead, film studio heads were provided with more autonomy away from the government. This also meant that they had to bear financial responsibility for successes and failures. The fifth generation had graduated from BFA in 1983 and would be the first to disrupt from Mao’s former rule.

The Fifth Generation: epic and exuberant

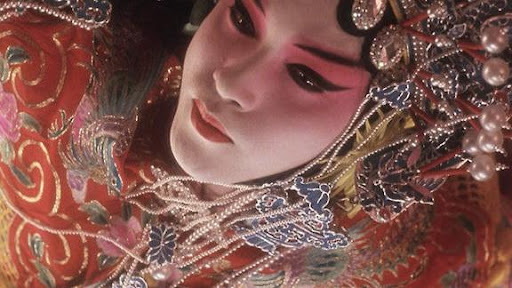

Chen Kaige (Yellow Earth, 1984, Farewell My Concubine, 1993), Zhang Yimou (Red Sorghum, 1988), Ju Dou, 1990), and Tian Zhuangzhuang, (September, 1984, The Horse Thief, 1986) were three of the famous filmmakers of this generation. They created epic productions with grand narratives, and coupled with exuberant sets with strong attention to detail on wardrobe and production design, this formula won them many fans.

They had a tendency to reflect on China’s history pre and post Mao, and there were often underlying themes of criticisms of the ruling powers and the transgressiveness of the controlled. For example, Red Sorghum (1988) by Zhang Yimou and Gong Li’s debut film, is set in an unknown idealised past, away from modernity such as cars, railways, and industry. Its setting in the countryside starts with the female protagonist being sent on a journey by her parents for a pre-arranged marriage with an old man who owns a sorghum wine distillery and has leprosy. This scene itself can be interpreted as the woman (signifying the powerless like women and common people) being repressed by her father and her husband-to-be – both representative of the father figure at large, which is the social system, the government, and Mao. Therefore, more freedom in film production post-Mao allowed these types of films to be made.

Farewell My Concubine (1993) by Chen Kaige. Source: VUDU Fandango

This fifth generation was onto a winning method that pleased both national and international audiences, while at the same time being able to socially criticise aspects of the Chinese government and culture. These films garnered international acclaim, including Red Sorghum (1988), which won the Golden Bear Award for Best Film at the Berlin International Film Festival, and King of the Children (1987) by Chen Kaige, which competed for the Palme d’Or at the 41st Cannes International Film Festival. Then in 1989, the Tiananmen Square massacre ruptured the country. Along with the country entering the market economy, this was a time for a new kind of revolt from filmmakers, which would be less beautiful and suave compared to fifth generation cinema.

The Sixth Generation: raw and gritty

“Let some people get rich first” – these infamous words by Deng Xiaoping during his tour of southern China in 1992 became the new ideology. The Post-Mao Reform Program had picked up momentum into capitalism in the 1990s, with the country experiencing a radical change not experienced since the Cultural Revolution. China shifted to a market economy, state-owned companies started to be privatised or shut down, and more than twenty million workers were laid off in the 1990s.

These young sixth generation, aka The Urban Generation filmmakers set out to record this transmutation of China. They were educated at the same state sponsored BFA as their predecessors, but they went against the state. The fifth generation were interested in the past, but this sixth generation was interested in the present. Rather than lush settings in the countryside, the urban generation was interested in the dirt and concreteness of the cities. They filmed Chinese cities in their metamorphosis, combining both fictional and documentary footage, with the incorporation of the documentary style in their fictional films being a recurring element.

Unlike their fifth generation predecessors, they did not work in film studies. With the advent of the new technology of hand held video cameras, they were free from the expenses of traditional film cameras, and the confines of the film studios that the fifth generation had spent so much time within. Their creations were controversial with the government, resulting in some of the filmmakers being banned from filmmaking, particularly when they had sent their films abroad to international film festivals, without obtaining prior permission.

Beijing Bastards (1993) by Zhang Yuan, Xiao Wu (1997) by Jia Zhangke, and Suzhou River (2000) by Lou Ye are three of some of the early films from the sixth generation. Suzhou River is particularly alluring as it retains the original independent cinema charms of this generation, it was well received internationally, and had not been screened in China. Its director, Lou Ye was banned from filmmaking for two years as he had not sought permission from the government beforehand to have it screened at International Film Festival Rotterdam.

Real fictional lives

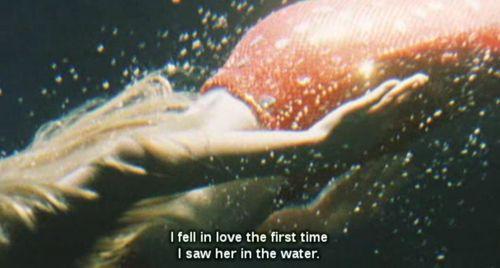

Suzhou River (2000) is named after the river, which flows through Shanghai, representing chaos, filth, and poverty. A motorcycle courier named Mardar in his mid-twenties delivers all kinds of packages for clients in confidence. One day he is asked to deliver a young woman called Moudan. They fall in love, but later she breaks up with him thinking that he has kidnapped her for ransom. She jumps in to the Suzhou River, Mardar is suspected of murder, and locals on the river claim to have seen her emerge as a mermaid. A couple of years later, upon release from prison, Mardar meets a dancer called Meimei who performs in a huge fish tank inside a bar/restaurant as a mermaid, and looks identical to Moudan. A faceless narrator guides us through the story.

Still from Suzhou River (Lou Ye, 2000). Source: Pinterest

This film has a narrative that is non-linear and fragmented. A lot of imagery is shaky from the hand-held camera and the editing is not smooth. It is metacinematic; a film about making a film, and making commentaries on other films, which are The Double Life of Veronica (1991) by Krzysztof Kieślowski and Vertigo (1958) by Alfred Hitchcock – both about identical women who don’t know each other yet are interconnected. Ye is stating through his clear cinematic inspiration that he is aware of the international art house language and that this is how he identifies himself as a filmmaker; different from the previous fifth generation and very self-aware.

The documentary aspect of this fictional film captures Shanghai in its actual transformative state making the story seem somewhat true; questioning the boundary between the real and the fictional. It subverted previous filmmaking techniques of the fifth generation, which focused on the fictional.

Identities are unclear. As the audience, we do not know if Meimei is actually Moudan, and the narrator cannot distinguish this either. Mardar is a filmmaker. He graffitis his pager number on walls across the city for those in need of film. His occupation also sits between reality and fiction. The very act of his pager number appearing on physical walls is a gateway to potential fictional worlds. The film is shot in the third person’s point of view, Mardar’s, and the narrator’s point of view; perspectives are blended. Apart from his hands sometimes, we never see the narrator, and just hear his voice. He is our guide through this new China and through this interplay of perspectives. He is also a character himself; an instigator of change to the story. Suzhou River sits in a liminal space.

The glittery mermaid outfit with the blonde wig that Meimei wears is a contrast to the bleak, greyness of the city. It transcends physical reality and approaches a reality, which merges ancient myth with the modern transformative nature of the internet, a medium where identities can be easily transformed. In this film and for this era’s youth residing within the reconfigerating cities of new China, physical identities can also easily be changed. The character of the mermaid that she wears is a Western import, signifying the new outsider capitalist element entering into this deteriorating socialist world. Mardar is enticed into this dream.

Later in the film, the narrator gives up his position and allows Mardar to take over. So there is an allowance in the change of perspective and the story of the film becomes a shared story that evolves. Yet, nothing is grounded in what can be deemed as true reality.

Perspectives change, and this new world that China is developing within itself, is a space where the virtual meets the physical, where the subjective meets the objective, and the ways of pre-capitalist China no longer hold the same validity that they did before. “I won’t look for her like Mardar, because I know nothing lasts forever,” says the narrator, adding to the notion that both the physical and mindscapes that these youths occupy, are in a state of constant flux. The city is in the process of being reconstructed, as are their own minds.

Through the international art house film circuit, the world was able to see 1990s modern China converging to what we now recognize as solid today. The sixth generation transgressively captured this new urban Chinese youth that was different from their previous generation. They were culturally and socially displaced, and trying to find a path within a newly emerging capitalist world, where reality and fiction intertwined.

- Emasculated: Angry Men in Korean New Wave Cinema - March 17, 2023

- Urban Subversion: 6th Generation Chinese Cinema - February 3, 2023

- Seoul: Post 1960s Genderised Cityscape - December 2, 2022