The rhetorical slogans of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) never do well in translation. But even in a language as famously succinct as Chinese, the newly minted political slogan unveiled at the 19th Party Congress of the CCP, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” is a mouthful.

Experts both within China and beyond rushed to figure out what meaning was hidden behind the clunky phrase, posting their interpretations on print and online media. The analyses often hinged on questions of power transition. Will the new era bring about a US decline? ‘No,’ say the Americans; ‘maybe,’ say the Chinese. Will China attempt to rule the world anyway? ‘No,’ say the Chinese; ‘maybe,’ say the Americans. Will there be a cataclysmic clash between the two superpowers? ‘Hopefully not,’ says everyone else.

What does China want? Obviously, the three-and-a-half hour long speech in which President Xi laid out his vision for the future of China is undeniably the officially sanctioned view, albeit lacking in detail despite its length. But as attention turns back to handling normal, day-to-day affairs with China, how should foreign observers understand where China is going? The question may be impossible to answer exactly, but Chinese media can provide clues, given one knows how to read and understand them. Here is the rundown of what to be wary of in reading Chinese media.

Let’s start with what many observers often get wrong about China. It is common in Western media to treat anything published by Chinese news, particularly on foreign policy, as an indication of official Chinese government policy. After all, everyone knows that Chinese media is controlled by the state, so any proclamation it makes naturally represents the official line. How could it be otherwise?

There are several problems with this approach. The treatment of any party mouthpiece as the voice of the party has generated alarmist headlines even from venerable news outlets such as Bloomberg and CNBC. During the border standoff between Chinese and Indian military at Doklam this summer, Bloomberg quoted the Global Times, a nationalistic newspaper – by most China-experts considered an unauthoritative tabloid – that specializes in hawkish editorials. Based on an article in the Global Times, Bloomberg said, “China may consider temporarily suspending investment or economic cooperation projects in India to ensure the security of these investments.” As it happened, the situation was resolved without much friction a few months later. No projects were closed down.

CNBC kicked the sensationalism up a notch. “China state media says US will ‘pay’ for ‘unjust’ sanctions” read the headlines during the latest peak of tensions on the Korean Peninsula, after the United States issued sanctions against some Chinese individuals with suspected ties to North Korea. Yet, the article itself clearly shows that “payment for unjust sanctions” is not what the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson, who was also quoted in the body of the article, had in mind. This is a clear misrepresentation of Chinese intent.

Similarly, when US President Donald Trump declared that he might not adhere to the “One China”-principle, the Guardian could not help itself but insinuate that China had plans to “take Taiwan by force” because Global Times insinuated this in an article. The Guardian justified the line stating that the Global Times, “sometimes reflects views from within the CPC.”

In all of these cases, the state media in question, Global Times, does have a purpose to fulfill in the Party’s communication portfolio, but that purpose is not necessarily to declare official policy. There exists, in fact, a distinct hierarchy of official communication in China. Global Times belongs at the bottom of it. Opinion pieces by university professors, retired generals and public intellectuals are common, but pieces by truly influential party members, policymakers or institutions are largely absent from its pages. Understanding where the sender of a particular message fits into the communications hierarchy is crucial in order to understand the importance of the message. When CNBC quotes party tabloids before party officials, the hierarchy becomes inverted.

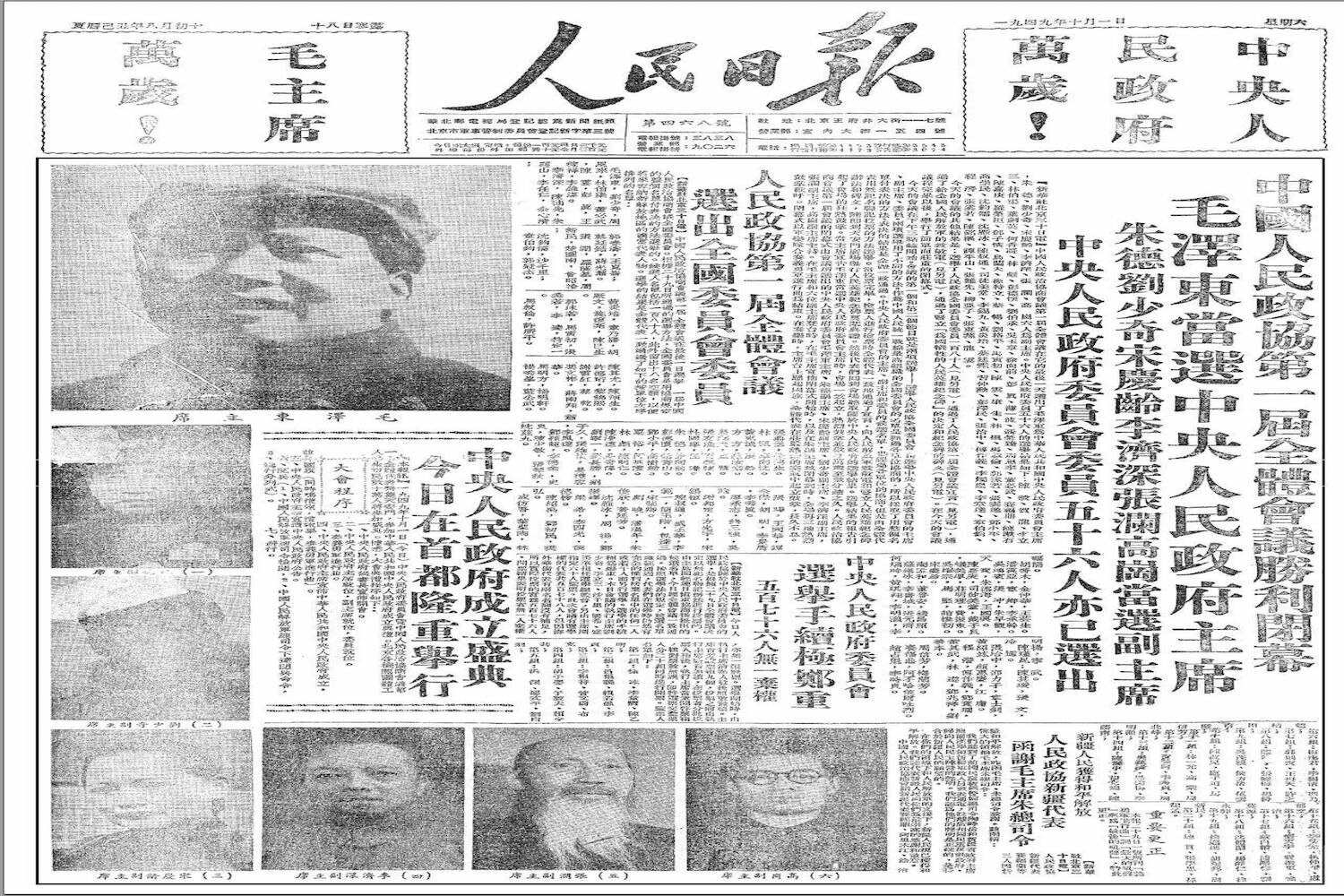

The most authoritative voice in Chinese state media is the People’s Daily. It is the mouthpiece closest to the lips of the CCP and, unlike the tabloids that Western media enjoys quoting, the language that People’s Daily uses is drier than the paper it is printed on. What’s more, its English language publication does not always accurately reflect what is published in the Chinese version of the daily. Many Western journalists turn to the English language newspapers like Global Times out of either convenience or necessity, and this is reflected in the tendency of Western media to use tabloids as a proxy for what China is really thinking. However, if the Chinese government wants to announce a major policy change through its media channels, People’s Daily is where it will happen first.

Within the editorial pages of People’s Daily, there is an internal hierarchy as well. The most authoritative of editorials and commentaries are the ones directly signed by members of the leadership.

The next level belongs to a group of pseudonymous editors. The most authoritative one is Zhongsheng (钟声), a name that literally means “sound of a bell,” but is homonymous with the phrase “voice of China” or “voice of the center.” An opinion piece signed by Zhongsheng, such as this recent one (in Chinese) urging improvement of the relationship between China and South Korea, represents a viewpoint that is solidly anchored within the central leadership. Similarly, the ominously named Guoping (国平) – “country at peace” – represents the opinion of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), one of the government’s main censorship bureaus.

Party tabloids do have a purpose to fill, but one that is separate from communicating official policy. They serve as a forum for “public discussion” of views that are more extreme than the current party line. As such, Western media should not use its ramblings to attempt to figure out what China is up to. Instead, these tabloids should be seen as yardsticks for measuring the range of politically correct opinions.

The second purpose is simply commercial. Chinese media producers are no different from their Western counterparts in this sense; they know that hawkish and boisterous headlines generate clicks and attention.

Chinese political slogans may be bewildering, the political culture opaque and the pen names cryptic, but the conclusion is not that one must absolutely learn Chinese in order to understand what China wants. Instead, readers and Western media coverage of China must simply be aware of what conclusions can and cannot be drawn from the information made available. Misconstruing Chinese intentions is dangerous because readers who turn to respectable news outlets will expect journalists to have done their due diligence in weighing sources. Applying the label ‘state media’ is an important journalistic practice so that readers can assess news with a dose of healthy skepticism, but the label should not be an excuse to treat all Chinese state media as a homogenous entity. There is a diversity of opinion despite what popular narratives might say.

These truly are global times for China, but we should seek to understand them through something other than the Global Times.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019