I have never been comfortable with the term “China watcher.” It is an awkward expression. It brings to mind a beardy, near-sighted academic in his ivory tower, peering through a spyglass at a country the West has never entirely managed to make sense of. Throughout the last two thousand years China has been romanticized, infantilized, colonized, ostracized and – eventually – recognized by the West as a player on equal terms.

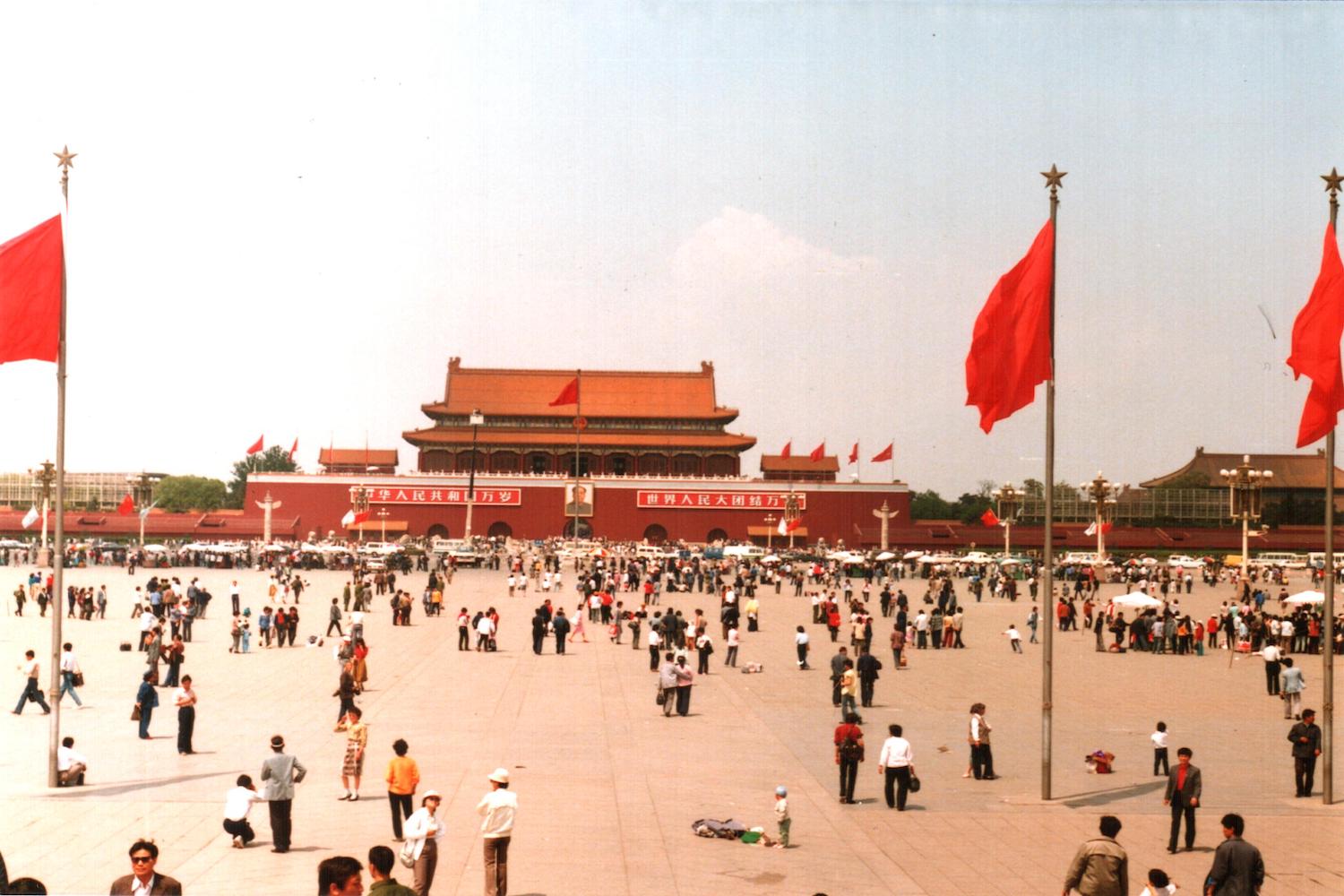

The capricious attitudes of China watchers towards their subject of study have given rise to a body of predictions and prophecies that is rarely precise, sometimes ironic, and often wrong. In 1996, James Baker, George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of State, considered it unlikely that there would be “a stable authoritarian China, for the foreseeable future.” This was in line with popular American thinking at the time, which considered the violent suppression of student protests at Tiananmen in 1989 to be a sign of the inevitability of Chinese democracy, rather than a sign of its impossibility. Baker went on to predict “internal jockeying,” which would eventually lead to a “transition to a more participatory political system.” He wasn’t even right about the jockeying, let alone the political transition.

Poking fun at such predictions with the benefit of hindsight is easy, and so maybe we should resist the urge. Nevertheless, the enterprise of “China watching” should perhaps better be labeled “China guessing.”

Baker’s failure to guess the future trajectory of China does not mean that all China watchers have been equally unfortunate. With some benefit of hindsight, one China watcher who did make an accurate prediction was Andrew Nathan. In 2003, after China had spent another seven years constantly disappointing James Baker, Nathan’s theory of authoritarian resilience was an explanation as to why democracy had yet to arrive in the Middle Kingdom. The theory noted four emerging themes in Chinese politics: norms of succession, meritocracy, institutional specialization, and increased political participation that strengthened the legitimacy of the Party.

The first three themes can be summed up with one word: “institutionalization.” The Party began to form political processes that were crucial to maintaining political stability. Altogether, this reduced the space for political infighting, what Baker termed “jockeying.” There was certainly a fair amount of cloak-and-dagger going on still, but the Party still projected and maintained a uniform, public image of technocratic competence.

As for the fourth theme – political participation – this was not the same kind that Baker had spoken of so hopefully. Individuals were allowed, even encouraged, to speak out against injustice, but any attempts at even marginally organized protests by groups of people were harshly repressed. At the same time, Party institutions channeled complaints in such a way that they were mainly focused on “specific local-level agencies or officials, diffusing possible aggression against the Chinese party-state generally.” For the Communist Party, political participation was not an end in and of itself, but rather a means to the end of political supremacy. The point was never to transition to a full democracy, but this halting form of political participation was often misconstrued as an indication that the Chinese were coming around to the idea of democracy. Even in 2015, I remember once attending a lecture at a Swedish university where an American professor designated China as “semi-democratic.”

As China has now moved from authoritarianism back to totalitarianism, from collective leadership of the Politburo to the supreme leadership of Xi Jinping, it is worth asking the question how the factors that made authoritarian resilience successful in China translates into “totalitarian resilience.”

First of all, any norms pertaining to leadership transitions seem to have been thoroughly discarded. Xi Jinping has extended his presidential term indefinitely, and it seemed more like an afterthought when he promoted his ally Wang Qishan, who by previous norms is too old for the position of vice president.

Second, China is still a meritocracy in some sense, perhaps even more than when Nathan penned his theory in 2003. As Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution has shown, the technocrats of yesteryear were political apparatchiks, engineers and natural scientists. By contrast, this generation of leaders are social scientists and economists, well-suited for the challenges that modern China is facing. However, close ties to Xi Jinping has allowed certain officials – such as the Chinese Communist Party chief in Beijing, Cai Qi – to “helicopter” into high positions without following more traditional career paths. The reemergence of such nepotism risks surrounding Xi with a crowd of sycophants, which can have catastrophic consequences for political decision making. Sure, the yes-men are smart and well-educated, but are they smart enough to second-guess Xi when necessary?

Third, at the latest meeting of China’s parliament, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a host of state institutions was streamlined and merged. In a sense, this can be read as a corrective response to the “overspecialization” of Party institutions, which has created many overlapping areas of responsibility. At the same time, the Party is putting the State even more firmly under its thumb; at the CPPCC, the phrase “core socialist values” was added to the State constitution. As veteran China watcher Bill Bishop put it in a recent edition of the Sinocism newsletter: “The Party Eats More of the State.” The Chinese state has of course always been under the control of the Party, but this consolidation of Party power suggests that we may have to add another theme to Nathan’s theory of authoritarian resilience: ideological control.

During Xi Jinping’s reign, ideological control has been turned up to levels unseen since Mao Zedong. The effect that this will have on Nathan’s fourth theme – political participation – is unclear. On the one hand, censorship and thought suppression are likely to increase (even outside of China’s borders), and this may suppress political activities all the way down to the grassroots; on the other hand, Xi Jinping is raising the stakes by taking personal responsibility of the Great Rejuvenation of China. Failure to deliver may spur discontent and cause serious popular backlash against the Party and against Xi himself. Chalk that up as my China-guess.

In sum, in my view “authoritarian resilience” is still a useful concept for understanding the lay of China’s political landscape, but the concept needs to be tweaked in order to account for China’s new totalitarian developments. In doing so, nothing about China should be taken as a given truth; history should testify to the fact that change is the only constant. Western China watchers in their ivory towers – and I suppose that also includes me – will have to keep scanning the country through their spyglasses and keep on China-guessing.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019