China uses its economic power to sow discord in the international community. And its working.

The 88-year old billionaire George Soros is a man with many enemies. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, that took place in late January, he made another one. The Hungarian philanthropist and investor, the face of neoliberal internationalism and the target of many outlandish conspiracy theories, singled out Chinese president Xi Jinping as “the most dangerous opponent to open societies.”

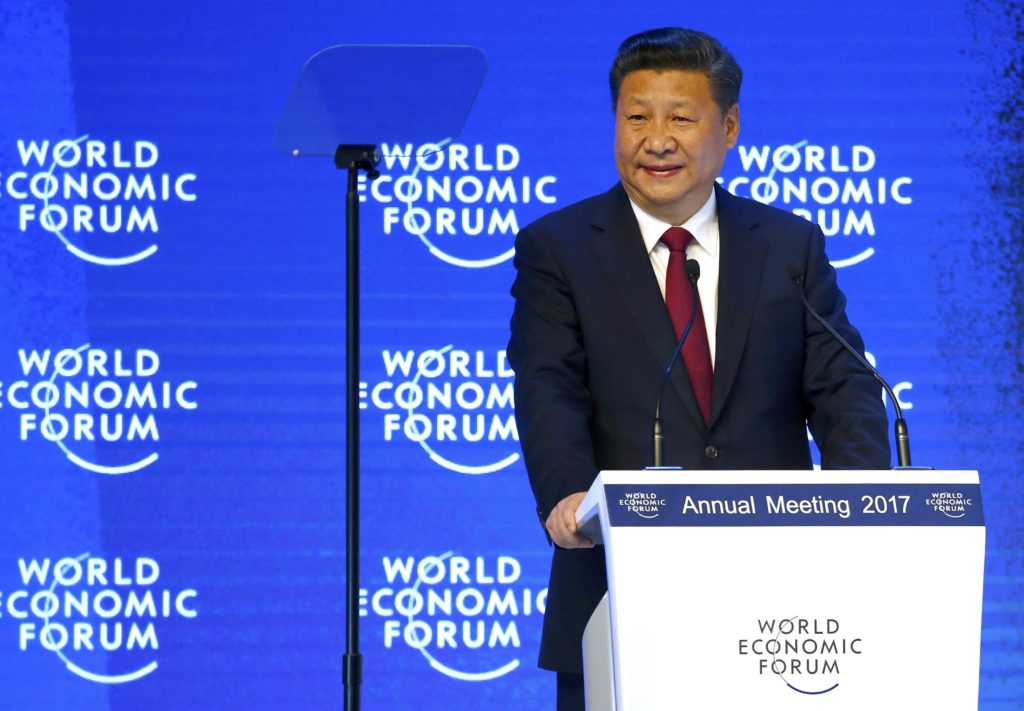

The significance of targeting the Chinese leader at the World Economic Forum was not lost on Soros’s audience. It was only two years ago that President Xi took the podium in Davos, casting himself as a protector of the very same internationalist ideals that Mr. Soros’ now accuses him of undermining. In that speech President Xi came out as a defender of free trade, multilateralism and “win-win cooperation.” Just two decades earlier, the notion of a Chinese free-trader would have been bizarre.

Many saw Mr. Xi’s speech then as an opportunistic attempt to seize ground that protectionist US president Donald Trump seemed willing to cede. But Mr. Xi’s speech was more than a hamfisted attempt to insert cast China as an alternative to the United States. Chinese presence at the World Economic Forum is one part of a systematic Chinese effort to influence – and in some cases undermine – international institutions and international governance in its favor.

Chinese President Xi Jinping attends the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland January 17, 2017 Image: REUTERS – Ruben Sprich

Port-ent signs of influence

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become the signature feature of China’s growing economic influence abroad.. The massive interlinked infrastructure project spanning many countries has come under scrutiny for saddling lesser developed countries with debt that is difficult to repay, and projects that sometimes fail to materialize. Projects that do materialize often fail to turn a profit.

The go-to example for the BRI’s failure is the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota, which Sri Lanka built using funds provided by the Chinese government. However, since the port is located only 100 miles south-east of the already busy port of Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, it failed to attract sufficient traffic to turn profit. Sri Lanka quickly became unable to service debt piled on through the project, and the Chinese government seized the opportunity to renegotiate the terms of the contract, essentially forcing the Sri Lankan government to lease the port to China for 99 years.

Through this maneuver, China now controls a port in the middle of the Indian Ocean, part of the “Road” half of its Belt and Road. (Confusingly, the Road goes across the sea, and the Belt across land.) While the project was an economic failure for Sri Lanka, it yielded significant geopolitical gains to China.

China’s control of ports worldwide has increased in the past decade. In Europe, China now owns 10 percent of all port capacity, and its economic influence in the European Union (EU) has brought about worrying changes in the behavior of some EU members. In 2017, Greece vetoed a joint EU condemnation of China’s human rights record in the UN. The move by Greece was widely seen as a result of Chinese investment in the country, particularly the port of Piraeus, in which a Chinese state-owned enterprise owns a 51 percent stake.

The Belt and Road Initiative Image: REUTERS

Although China has formally signed the UN Declaration of Human Rights, which claims that human rights are universal, in practice China maintains that human rights are relative. Undermining EU support for universal rights in the UN was therefore a double-whammy for China, emphasizing its growing influence on international institutions. It’s no wonder EU officials darkly joke that one of Mr. Xi’s favorite expressions – “win-win” – simply means that China wins twice.

China’s tactic of buying up strategic ports and foreign enterprises stands in stark contrast to what China allows in its own backyard, where foreign firms are required to create joint-ventures with Chinese firms. Few foreign firm control the majority of their stake in Chinese operations, and those that do still suffer to forced technology transfer. This is another point in case that China is not living up to its promises to follow international norms of reciprocation in trade relations.

Not all of China’s attempts abroad have been successful. European nations have thwarted several Chinese investment attempts, like the Chinese plan to buy up a port in the south-western Swedish city of Lysekil. But politicians in Europe are becoming savvy to China’s growing clout. This year an annual defense and security forum attended by Swedish politicians and policymakers treated China as a separate topic for the first time. This is a shift of focus in a region that has long viewed Russia as the main threat to its security.

At the same time, the EU is undergoing a sustained period of political turbulence and dissatisfaction among many of its members. Forced austerity measures imposed by larger European neighbors like Germany, has caused much resentment in Greece in the wake of the Euro-crisis. Russia has long hoped to use divisions within Europe to its advantage, but resentment and discontent among EU-members is also fertile ground for China to grow its own influence.

Sowing discord

Closer to home, China has found that economic influence over regional countries can be useful as well. China claims almost the entire South China Sea as its own territory, a claim that has ruffled feathers of ASEAN nations who also have claims in the South China Sea. In 2016, an international tribunal in The Hague ruled in favor of the Philippines in the case of its territorial dispute with China. China refused to accept the ruling, calling it a “farce.”

Shortly thereafter, Cambodia refused to sign a joint statement at a summit of ASEAN leaders if it contained any mention of the tribunal’s ruling. China has invested heavily in Cambodia, and trade with China amounts to 25 percent of Cambodia’s total GDP according to statistics from the World Bank. Conversely, Cambodian trade with claimants in the South China Sea, its fellow ASEAN members, is only half of that. Just like in the case of Greece, Chinese economic influence over Cambodia (as well as Laos and Myanmar) may be swaying the activities of a regional institution in its favor.

George Soros, Chairman, Soros Fund Management, USA, is captured during the session ‘Redesigning the International Monetary System: A Davos Debate’ at the Annual Meeting 2011 of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, January 27, 2011. Image by World Economic Forumswiss-image.ch/Photo by Michael Wuertenberg

Same old, same old?

Although he had emigrated to the United States by the time the Soviet Union invaded his native Hungary, George Soros is old enough to remember how opposition to an illiberal hegemon spelled doom for his homeland. In 1956, the nation revolted against Soviet-imposed rule, but Soviet invasion quickly quenched the revolution. Hungary languished under Communist rule until the end of the Cold War. Seeing a communist leader greeted with applause at one of the world’s most unapologetically capitalist gatherings must certainly have been troubling for Mr. Soros.

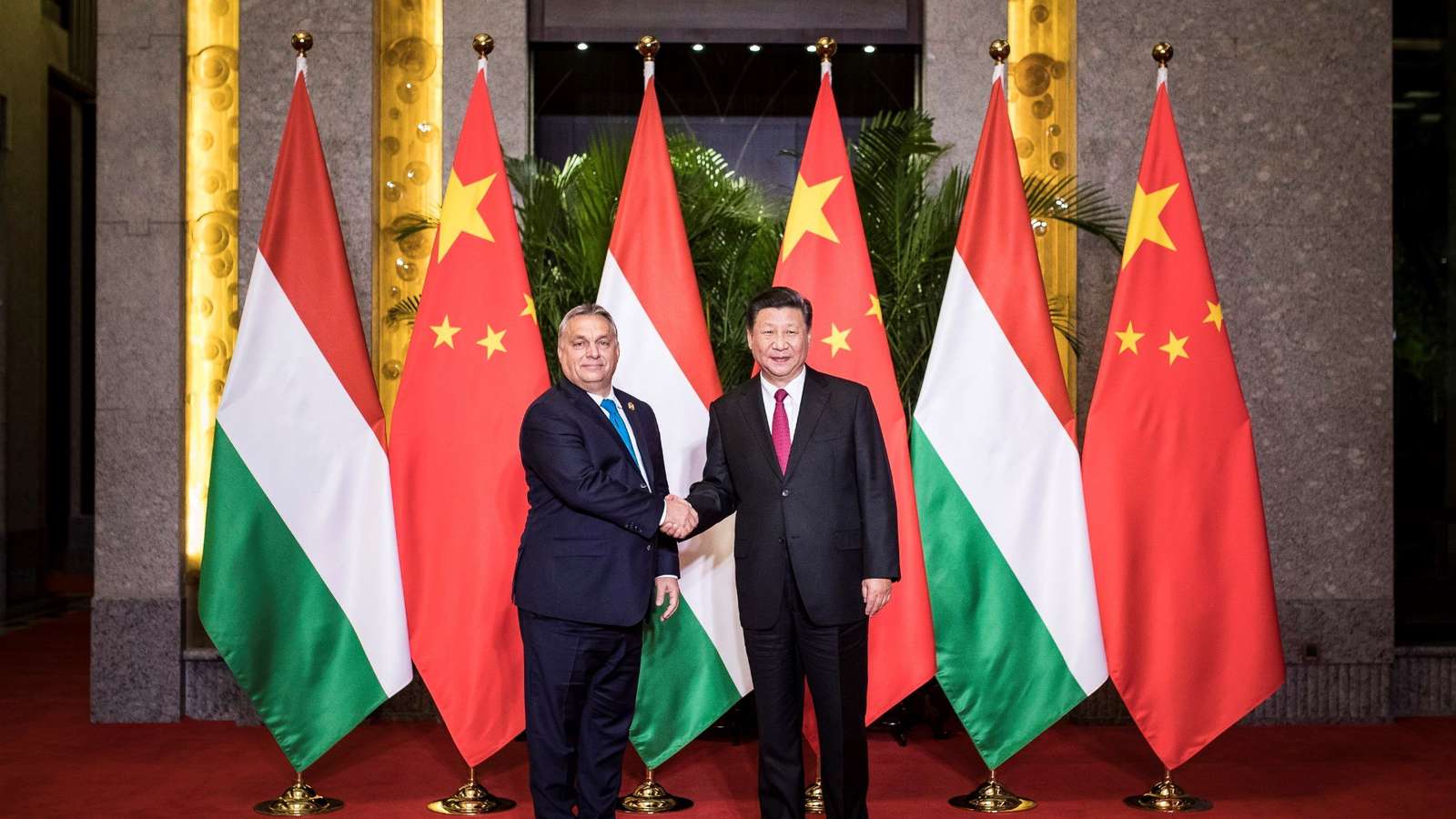

Today, George Soros is a reviled figure in Hungary. Prime Minister Viktor Orban has tapped into many of the outlandish – and often anti-semitic – conspiracy theories that cast Mr. Soros as the mastermind of a villainous conspiracy that would force the country to open its borders to refugees. At the same time, Hungary is one of a handful fringe EU-members (including Greece and Italy) whose policy towards China has been characterized by the European Think-Tank Network on China as “passive and potentially counteractive” to EU political values of democracy, human rights and rule of law. Hungary is also one of the most vocal critics of what it perceives as increasing EU federalism.

There is a fault line which runs right through the EU, and China is ready to exploit that fault line for its own gain. In November last year, Mr. Xi and Mr. Orban met in Shanghai hoping to “strengthen political support and trust” between the two countries. They also agreed on increased Sino-Hungarian cooperation on critical infrastructure projects, such as a Hungarian-Serbian railway which China considers a part of its Belt and Road. Mr. Xi clearly views Hungary as another notch in his economic Belt. To Mr. Orban, the grand and generous Eurasian infrastructure project offers an attractive alternative to the bureaucracy-laden European Union. If the EU is to counter growing Chinese influence over its members, it must show that for anything that China can provide for EU-members, the EU can provide more. Otherwise it risks having China chipping of the most Eurosceptic members, one by one.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019

1 Comment

Episode 5 - A "Green and Clean" Belt and Road? - Novasia

6 years ago[…] Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has given rise to two broad concerns within the international community. It has been criticized for funding environmentally […]

Comments are closed.