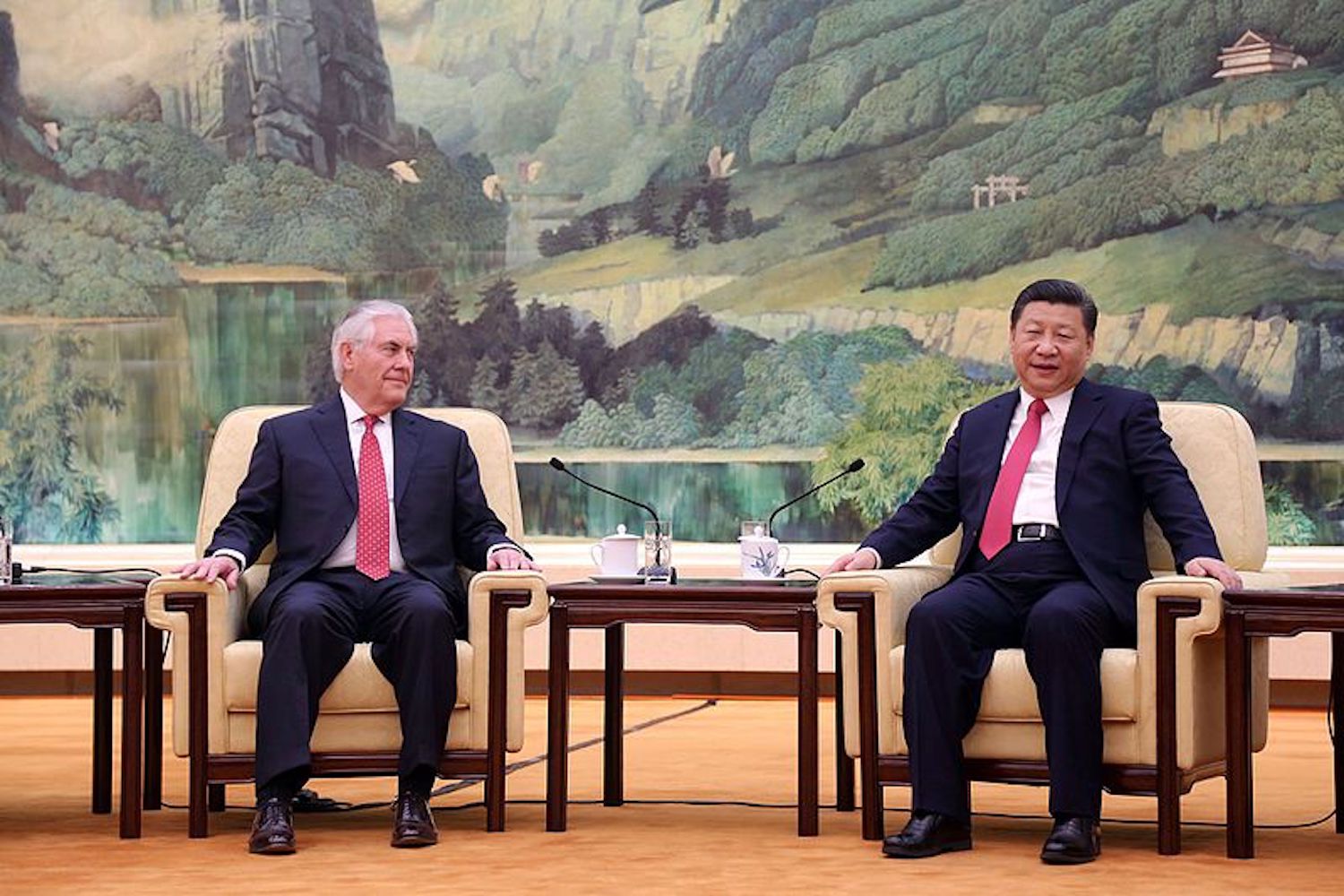

On March 13, President Trump fired his Secretary of State Rex Tillerson via Twitter and replaced him with CIA Director Michael Pompeo. The news was hardly surprising. There has been a noticeable disconnect between Trump and Tillerson since the day the former CEO of ExxonMobil took office at the State Department. Tillerson’s role as the top US diplomat has been frequently undermined by the President’s impulsive outbursts. According to The Washington Post, Trump’s reason for firing Tillerson was their disagreement about how to handle North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un. Apparently,Trump decided to meet Kim without consulting Tillerson.

The firing of Tillerson is emblematic of American foreign policy under the Trump administration, unstable and understaffed. Even while making North Korea his top priority, President Trump has yet to appoint an ambassador to South Korea, and the State Department (which Tillerson, the former boss, treated with contempt) still lacks any appointee in charge of the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

In dealing with China, instead of relying on the State Department, the governmental body supposedly in charge of foreign policy, Trump has chosen to construct a circle of hawkish advisors, which currently consists of officials such as Steven Mnuchin, Peter Navarro, Larry Kudlow and the more low-profile Robert Lighthizer, architect of Trump’s impending trade war on China.

Trump’s singular and furious focus on trade has made him blind to any other developments in relation to China. He has completely abandoned the South China Sea, ceded massive ground to China in the field of sustainable energy, and he is doing nothing of substance to challenge the boom of Chinese AI technology (although the United States is still ahead of China in this regard). Not to mention Donald Trump’s indifference to human rights issues and democracy; when Chinese President Xi Jinping abolished the term limits of his office, President Trump sounded admiring when any other US President would have sounded gravely concerned. In short, the United States currently lacks a comprehensive China policy.

If the problem for American foreign policy is a lack of comprehensiveness, then the Chinese problem is exactly the opposite. The Chinese foreign policy establishment is an alphabet-soup of overlapping party-state institutions that have to climb over one another to get President Xi Jinping’s ear.

However, President Xi seems set on gearing up the Chinese bureaucracy for the upcoming clash with the United States. It is rumored that two of these overlapping institutions – the International Liaison Department Office and the Office of the Central Leading Group on Foreign Affairs – will be merged into one. This streamlining of Chinese foreign policy is a logical step for a nation attempting to compete with the United States on more even footing and fill out a bigger role for itself within the international community.

What may be even more significant is a little talked-about change in the very top leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. When Xi was elevated to President indefintely at the Chinese People’s Consultative Conference last week, his right-hand man and long time friend Wang Qishan was appointed Vice-President. Wang was the man in charge of the most important of Xi’s political campaigns during his first five year term – the anti-corruption campaign. It is a telling sign of Xi’s priorities that Wang’s new main area of responsibility will be the Sino-US relationship. Wang is a veteran politician with considerable economic expertise, and he will prove an able opponent to Trump’s hawkish tradeteam. What’s more important, unlike Trump’s crew, Wang will have the full support of his nation’s political apparatus behind him.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019