Xi Jinping wants recognition from the international community. With his house in order, can he use a tougher stance on North Korea to gain some?

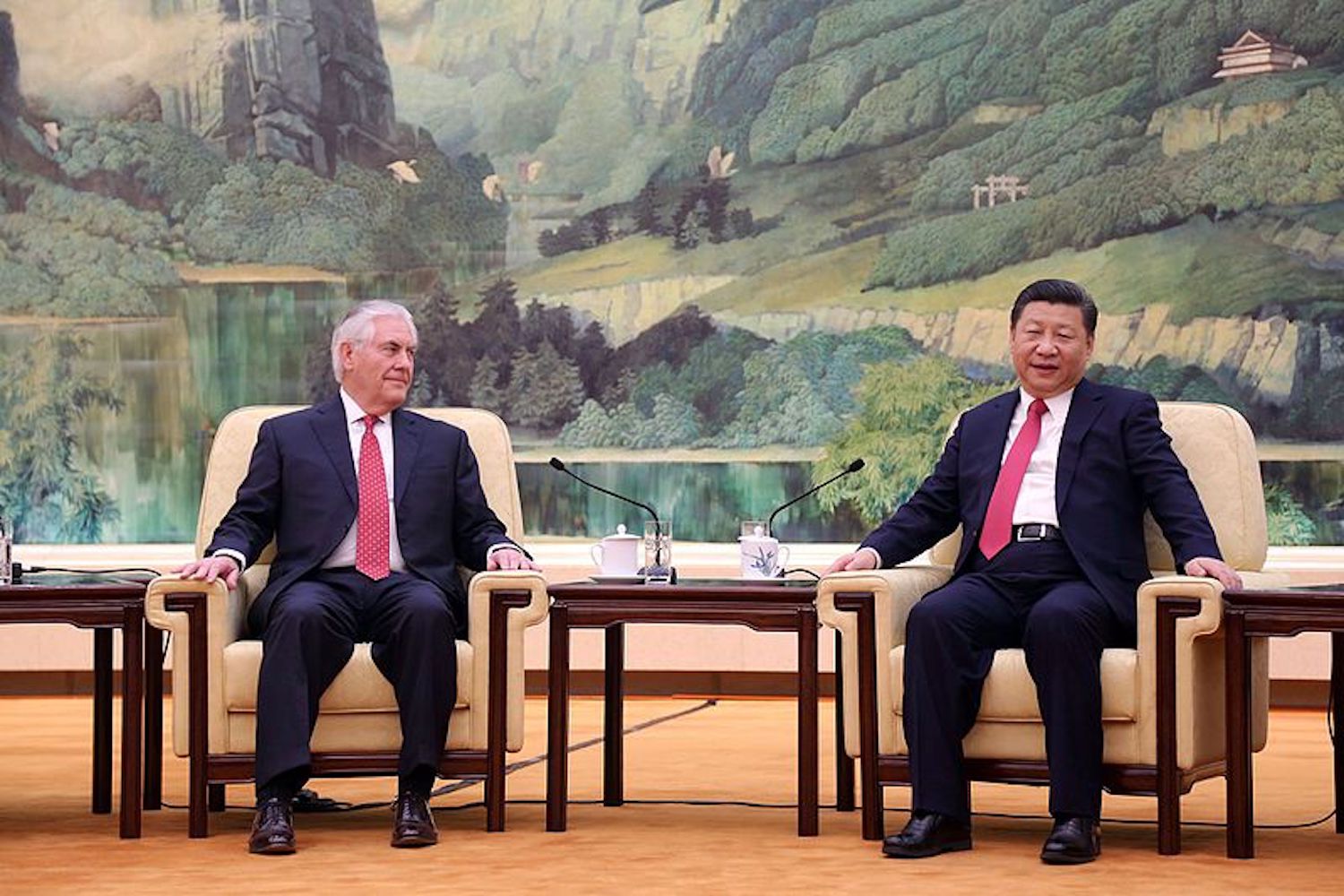

When Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with US President Donald Trump in Beijing on November 8th, he does so coming out of the 19th Party Congress as the strongest Chinese leader since Deng Xiaoping, with the solid record of his first term in power and the full might of the world’s biggest political apparatus at his back. Donald Trump, for his part, arrives with the chaotic record of his first year in power, low ratings, and therefore a desperate need for a clear win in the issue where he has staked most of his foreign policy capital – the North Korean nuclear crisis. The domestic positions of the two leaders could hardly be more different.

This is worth pointing out, because if Donald Trump gets what he wants from China – enforcement of sanctions – the outcome is not going to be determined by the strength of his own demands. Rather, the outcome will be determined by the extent of which Trump’s demands align with Chinese interests in general, and Xi Jinping’s vision for himself in particular. And now, with his domestic position safely consolidated, it is the perfect time for Xi to show that China can contribute in meaningful ways to the international order, like he promised in his Davos speech in January. Already, China is making a large-scale push for influence in international institutions, such as Interpol and UNESCO (the latter from which the US recently decided to withdraw). International goodwill is thus becoming increasingly valuable to Xi.

However, the latest developments in the North Korean nuclear crisis have come at an awkward time for a leader who is vying to seize the international high-ground that the US president seems so willing to cede him.

Several times already has North Korean leader Kim Jong-un made Xi Jinping look like he is not up to the task of international leadership: first by detonating a hydrogen bomb so powerful that tremors could be felt throughout China’s north-eastern provinces, shortly followed by a missile launch across Japanese airspace, just as China was hosting a gathering of BRICS-leaders in Xiamen.

China vehemently opposes what it calls the “China responsibility theory” – the idea that the onus is on China to solve the North Korean issue. This stance conveniently glosses over the fact that China is in fact diplomatically incapable of taking North Korea down a peg, even at a time when doing so lies in China’s own interest. The reason for this is the dismal state of relations between the two countries. Even before the hydrogen bomb test in September, Kim Jong-un’s ruthless purges of those around him with close ties to China – such as his uncle Jang Song-thaek and his half-brother Kim Jong-nam – had already brought the relationship to its lowest point in decades, a relationship that has always been fraught with suspicion and distrust. In short, China’s political leverage over North Korea is, and has always been, limited. There is no reason to believe that this dynamic between protector and protégé will change meaningfully after the Party Congress.

The escalations on the Korean Peninsula have coincided (or Kim Jong-un has deliberately designed them to coincide) with the ramping up of the political circus before the Party Congress. This has happened in a way which has prevented the Chinese leadership from taking any radical measures for fear that a miscalculation would upset the internal power balance before this important event. Until now, Xi has been put in a damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t-situation where action may weaken him but inaction makes him look indecisive and fumbling to the international community. Because domestic concerns always trump foreign crises in China, Xi has chosen the second option.

The 19th Party Congress represents both a significant shift in Beijing’s foreign policy, as well as a consolidation of the domestic power that underpins it. With the Party Congress over and done with, Xi’s predicament should essentially resolve itself. He will have enough political space that he can afford to shake up the board. And herein lies the cause for cautious optimism among those who wish to see a tougher Chinese stance towards North Korea.

North Korea has increasingly become an obstacle for China on its path into the international community, and therefore China might have more to gain than to lose from reconsidering “China responsibility theory” on North Korea. Previously, China has tended to slack off on North Korean sanctions as tensions subside, but now there is incentive, as well as opportunity, to commit. Viewed in this light, we might expect China to handle the latest round of sanctions with considerably more stringency. Whether the sanctions will actually work is not even the crucial point, by simply complying with sanctions China sends a powerful signal to the international community.

The Xi Jinping that Donald Trump will meet in Beijing will be a leader whose interests now align with his own to a certain degree, and there will be an opportunity for a win-win deal. Xi Jinping will be able to raise his profile abroad as an international leader ready to assume responsibility. At the same time, he will be able to provide Donald Trump with a much-needed win. This will surely play well at home too: China gives what it wants, America receives what it can get.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019