“When social discourse claims that one does not exist, or in other words, when one is coerced into remaining a non-social entity, how does one effect changes…?”

– Mapping the Vicissitudes of Homosexuality, 2001, page 67, Seo Dong-jin

BTS, Blackpink, Parasite, and Squid Game have taken the world by storm. Internationally, hallyu (한류, or ‘Korean Wave’) fans have increased 17-fold in the past decade to approximately 156 million. Korean has become the 14th most widely spoken language in the world. With its international growing prominence through soft power its home policies can sometimes be overlooked, which includes ambivalence to its sexual minorities. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI) continue to suffer, partly because of government policies and partly because of its conservative heteropatriarchal Confucian culture. We take a brief look at some of the problems sexual minorities in South Korea face, the start of gay rights activism, Queer Korea – a new book exploring the history of sexual minorities in Korea, the expanding depictions of homosexuality in media, and the possibilities for greater inclusion.

Homosexuality now: legally and socially

On 3rd April 2003, South Korea declassified homosexuality as being “harmful and obscene,” but many issues remain to be solved.

In 2019, a survey showed that 45% of LGBTQI youth under the age of 18 had attempted suicide, while 53% had attempted self-harm.

Since 2007, an Anti-Discrimination Act has failed to be implemented. Currently there is no law to prevent direct and indirect discrimination based on aspects that include sexual orientation, gender, race, and disability. Conservative Christian groups have had strong voices preventing developments. Until the 1990s, there were very few voices in mainstream society who had openly spoken about gay rights.

1990s: the turning point

Historical research into non-heteronormative citizens stretches back decades, however the 1990s was a turning point for gay and lesbian activism, and the emergence of non-underground LGBTQI culture. The usage of terms, such as ‘lesbian, gay’ and ‘trans’ are words that we employ freely these days, however, in South Korea prior to the 1990s, there was not a clearly accepted mainstream gay and lesbian identity. Sexuality was viewed as transient, meaning that men and women could be seduced or fall into unseemly homosexual actions, but it did not mean that they were homosexual. Men who had sex with men were referred to as ‘homos,’ and ‘gay’ meant a transgendered person; both had negative connotations.

In 1992, lesbian African-American US military employed Toni, founded the lesbian group, Sappho. Later, she went on to place an advertisement at information services on base, as well in two English newspapers, the Korea Times and the Korea Herald. Her aim was to reach out to and try to find other queer people to meet. At the time, there was an increasing number of non-Korean people living in South Korea, who worked mostly as English teachers. Eight people replied to Toni’s ad, this included three Korean lesbians and one Korean-American gay man called Chang Gene-suk (Kwon Kim and Cho, 2011: 210, 211).

Chang Gene-suk went onto create Ch’donghoe (초동회), the first lesbian and gay organisation. However, conflicts between the lesbians and gays occurred, as the lesbians viewed the gay men as sexist. They saw more gay projects being funded instead of lesbian ones. The majority of the funding was coming from gay men who owned gay bars in the Seoul districts of Itaewon and Jongno. The two groups went their separate ways. Ch’donghoe (초동회) dissolved and in turn, Chingusai (친구사이, meaning ‘between friends’) was established in February 1994. Its aim was to provide support, council, and create a social environment for their gay members to meet. In November 1994, the lesbians established KiriKiri (끼리끼리, meaning ‘amongst ourselves’), with similar objectives to Chingusai (친구사이) (Kwon Kim and Cho, 2011: 211).

The public had often viewed queer people as being diseased and engaging in group sex. A new awareness of homosexuality in South Korea really started after April 1995, when university students, Seo Dong-jin and Lee Jung-woo created gatherings for sexual minorities at Yonsei University (the club was called ‘Come Together’) and at Seoul National University (named ‘Maum 001’). A couple of other universities followed suit (Lee, 2015: 165).

Seo and Lee were invited to TV talk shows and radio programs, and for the first time, the South Korean public could put the concept of homosexuality to a face, however, their strong hostility persisted.

Seo introduced the idea of ‘sexual politics’ for people to understand sexuality more clearly. He also tried to create communities for gay men to meet for other reasons than a dalliance – through friendships and communities. The rise of the internet coincided with these university movements, so that gay people could find others online and sometimes eventually meet offline. These were the processes of the modern formation of lesbian and gay identity, which then went on to expand into lesbian, gay, and trans communities (Lee, 2015: 165).

1990s news excerpts from a short documentary on the creation of the gay area in Itaewon, Seoul by STEAK FILM. Source: STEAK FILM

Queer Korea

For a community and culture to know its place in the world and to be grounded within that history, it needs to know where it has come from. Most research on queer Korean history has been on the 1990s onwards and it is easier to acquire. However, in 2020, Todd A. Henry released Queer Korea, a book consisting of essays focusing on non-normative sexuality and gender, predominantly on the pre-1990s going back to the 1920s. The topics include an analysis on drag through shamanic rituals, same-sex love in colonial Korea, 1960s cautionary fiction on lesbianism, and the neoliberal gay post-Asian Financial Crisis. A Korean version is currently in translation. The focus of this article, The Queers are Here, is on contemporary queerness in South Korea from the 1990s to now.

Within the book, an essay by John (Song Pae) Cho titled The Three Faces of South Korea’s Male Homosexuality: Pogal, Iban, and Neoliberal Gay provides insight into the development of gay men from the 1970s through to the early 2000s.

The section on Neoliberal Gays is particularly relevant to this article’s focus on South Korean sexual minorities “remaining a non-social entity.” With the Asian Financial Crisis from July 1997, many South Korean citizens lost their livelihoods. The future of the patriarchal family structure was looking bleak, so in turn, the government along with the media “revived the older ideology of “family as nation.” The heterosexual normative family model was promoted by discrimination against non-married people and homosexuals. This included offerings of social benefits to married heterosexual couples, and editorials of family breakdown such as divorcees and same sex couples made clear the price of familial disunity. The developments of the lesbian and gay community prior to 1997 had lost traction. Financial insecurity loomed especially for non-heterosexual men, and without the support of a wife and/or children, the only feasible options for many were financial security and self-development, which resulted in their retreat from the gay community. The internet, which had earlier served gay men to make friends and find communities, could now also be used more for hookups. Ensuring that a gay man could fit into heteronormativity, while engaging in his sexuality under the radar.

Besides from this chapter, the actor and television personality, Hong Seok-cheon serves as an example of what can happen when one does not hide. He became the first celebrity in South Korea to come out as gay in 2000, which resulted in him being fired from television programs, losing acting jobs, and experiencing strong verbal abuse and discrimination. He became a living example of how one’s life could be turned upside down by revealing their true self in South Korean society.

Within Queer Korea, another essay titled Avoiding T’ibu (Obvious Butchness): Invisibility as a survival strategy among young queer women in South Korea by Layoung Shin, is an eye opener. In the late 1990s boy bands such as H.O.T were becoming immensely popular with teenage women. Some of the fans went as far as imitating their idols by having their hair cut short, donning baggy men’s clothes, as well as altering their way of speaking and gestures to resemble the men they admired. This was the start of fancos (fan costume play) and was a haven for some women who had or wanted a more masculine demeanour. Some of them were attracted to and would date women who were complementarily, more feminine in appearance and character. However, as time went by and people started to associate short-haired women with lesbianism, both butches and fems (feminine lesbians) started to shy away from these associations, as they did not want to arouse suspicion. As the fear of being outed for both increased, appearing to be heterosexual in both dress and behaviour became a necessity for survival.

In addition to the above, during the early 2000s, some girls schools in South Korea implemented homosexual checks to call out those who may be walking on the wrong side of the track. Behaviour amongst girls such as hugging, letter sending, holding hands and having short hair was questioned and examined. Anyone who suspected another student of being a lesbian was asked to report them. This was a systematic operation to enforce fear and promote heteronormativity. These are some of the topics discussed within Queer Korea.

Cover of Queer Korea. Image from the film, Jealousy (질투/1960), by Han Hyong-mo. Source: Duke University Press

Homosexuality as a spectacle

So far, we have looked at some examples of the potential downfalls that homosexuals faced when coming out. On the other hand, homosexual topics on screen and stage have flourished. The musical, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, about an East German genderqueer rock singer, trying to transform their life of pain through music, was South Korea’s ‘longing-running and steady-selling musical’ – from 2005 to 2021, it was performed approximately 2,300 times. Trance, the oldest drag club in Seoul not only had queer customers before the pandemic, but seemingly an increasing number of heterosexuals too.

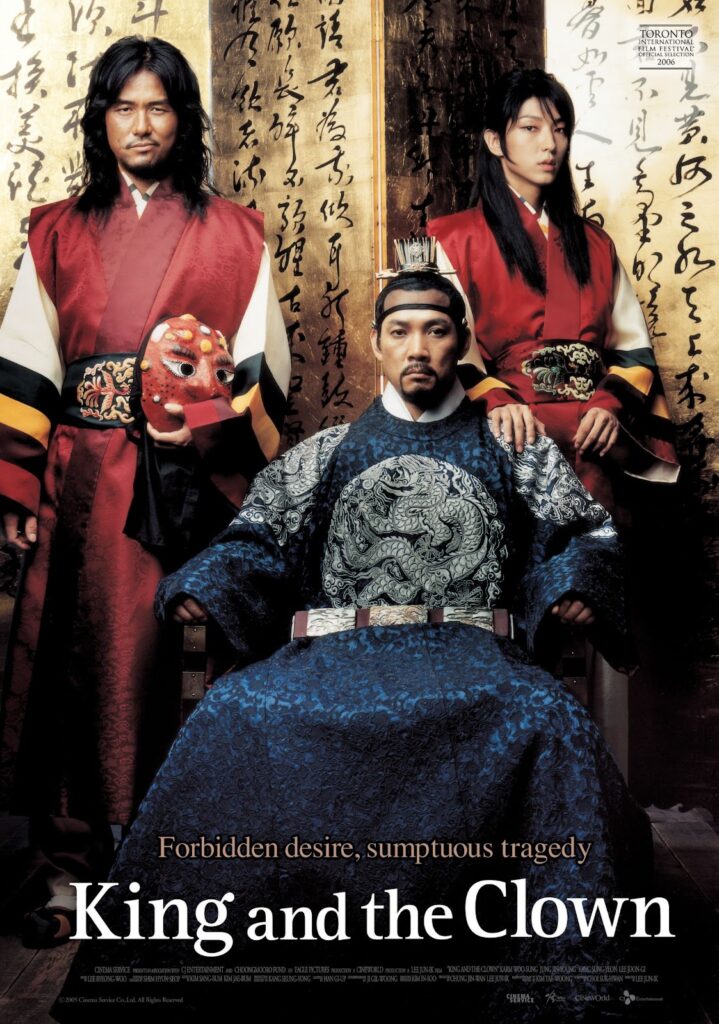

In 2005, the film, The King and the Clown was seen by more than 12 million people (one quarter of the country), becoming the nation’s most successful film in Korean cinema history. It is set in the 16th century, and features two male itinerant clowns who are hinted at having a homosexual connection. The feminine looking male clown arouses the fascination of the king, and so a love triangle is set in motion. The film’s title in Korean translates to “The King’s Man” – gayer than the English title. The director, Lee Joon-ik’s research into the story involved consultation with a surviving itinerant clown, 77-year old Kim Go-bok, who spoke about how it was difficult for them to get married, as their income was so low. These male clowns would spend long periods of time together, and often a masculine and a feminine clown would become a couple. Even some clowns who had wives would go onto leaving their marriage for a fellow clown. “Relations between men were very sincere and genuine. It was an amazing, remarkable relationship, much closer than anything between a husband and a wife.”

There is a coexistent contradiction between the socially accepted depicted quality of love evaporating barriers, and a culture suppressing its people.

The King and the Clown (2005), by Lee Joon-ik. Source: IMDB

Expanding sexualities on screen

With regard to many queer South Koreans feeling the necessity to masquerade as heterosexuals, a middle-ground was represented in Two Weddings and a Funeral (2012) by Kim Jho Kwang-soo. It depicts a story of a gay man and a lesbian who decide to marry to appear as a “normal” couple to their family and friends – even adopting a child. Their scheme allows them all of the benefits that heterosexual couples can obtain, while secretly being themselves. The film was not a commercial success, but its message was a clear indicator of the grievances that non-heterosexual people face from their family and society, and a potential way out.

Films with protagonists who cross the lines between homosexuality and heterosexuality have appeared on screen in the last few years. House of Hummingbird (2018) by Kim Bora, features a 14-year old girl who has a boyfriend, but is also involved in a relationship with a girl. The lesbian-themed film, Moonlit Winter (2019) by Lim Dae-hyung, won a multitude of awards including Best Director at the 2021 41st Blue Dragon Film Awards. A seemingly heterosexual middle-aged South Korean single mother, who revisits an ex-female girlfriend. These kinds of films, which are drawing a link between the known and safe heterosexual world in South Korean society, and the unknown other, are necessary for further highlighting the complex sphere of sexuality beyond the seemingly binary norms.

Moonlit Winter (2019), by Lim Dae-hyung. Source: Asian Wiki

New narratives

In conclusion, whilst there are many LGBTQI activists and gay people who are out in South Korea, there appears to be a majority who are continuing the trend from the late 1990s and early 2000s, which is to camouflage within the heteronormative masses, as this is a safer social space to exist within. However, this concealment slows down propulsion for the respect and integration of sexual minorities in the long term.

Even though many citizens support the implementation of the Anti-Discrimination Act, most heterosexual Korean people never see or meet someone they know to be homosexual. Therefore, the need for the implementation of this law has less weight and necessity, compared to the protection of women or other races, who are far more common to see in various workplaces and schools. In order for South Korea to progress with its understanding and acceptance of sexual minorities, more LGBTQI people must come out. Needless to say, with a multitude of constraints, this is far easier said than done. A research survey by the LGBTQI youth group, Dawoom, found that 7 out 10 LGBTQI youths hide their identity at work, and more than 40% who have revealed their sexuality, have experienced negativity towards them in the workplace.

There is optimism though, as 2019 research from the PEW Research Center states that 79% of 18-29 year old South Koreans believe that homosexuality should be accepted by society. Whereas in contrast, the percentage for those who are 50 years old and up drops to 23%. An increasing number of media channels, including JoongAng Ilbo, YTN, and SBS have been giving the floor to these previously silenced minorities.

In order for progress on the gender and sexuality front in South Korea, firstly, changes need to be made through laws. Secondly, new narratives, which transcend outdated notions of gender and sexuality are necessary. The aforementioned films, House of Hummingbird (2018), and Moonlit Winter (2019) are examples. Another is an exhibition in 2021 titled Home Sweet Home at Gallery OOOJH, which featured a video piece, I Smell Wedding Bells (2021) by artist, Minki Hong, who interviewed various members of his family members on their views and concerns about having a queer son. This piece was a bridge between traditional heterosexual thoughts and a younger queer identity, with discourse being the key bridge. Kim Jho Gwang-soo released Made in Rooftop in 2021, a film that anachronistically depicts a gay man with HIV living in a South Korea where homosexuality is no longer an issue. New narratives like these need to be made available to the masses, in order to further understanding.

In South Korea, traditional cis-gendered heteropatriarchal Confucian culture sits – unknowingly – alongside the so called ‘sinners.’ In offices across the nation, women and men work shoulder to shoulder with other ‘straight’ (married) colleagues, who are discreetly on their apps looking for the same sex to play with. Perhaps we will see the two divided selves uniting in the not too distant future. Validations of alternative ways of perceiving and living in media are necessary.

The queers are here and always have been. Media is a crucial medium for them to gain recognition as existing social entities.

Note: The title of this article, ‘The Queers are Here’ is taken from STEAK FILM’s online event in 2020 held in collaboration with Perpetual Spring at MMCA Seoul – an architectural project by New York-based Obra Architects. In ‘The Queers are Here’ they showcased three queer artists, two of whom were South Korean. STEAK FILM holds cinematic events throughout Seoul and internationally, with an aim to facilitate awareness and dialogue, particularly on taboo topics.

A special thank you to Seo Dong-jin and Todd A. Henry for their feedback and support with this article. To Hyun-young Kwon Kim and John (Song Pae) Cho – the authors of ‘The Korean gay and lesbian movement 1993-2008: From “identity” and “community” to “human rights”’ (2011) for shedding insight into this topic. For the same reason, also a special thank you to Eun Young Lee for her dissertation titled ‘The Rhetorical Landscape of Itaewon: Negotiating New Transcultural Identities in South Korea’ (2015).

- Emasculated: Angry Men in Korean New Wave Cinema - March 17, 2023

- Urban Subversion: 6th Generation Chinese Cinema - February 3, 2023

- Seoul: Post 1960s Genderised Cityscape - December 2, 2022