By Elisa Chavez

Despite groundbreaking democratic developments since the approval of the 2008 Constitution, the press in Myanmar today is more threatened than ever with record-high numbers of imprisoned journalists. Just a short five years ago, media censorship was abolished for the first time in over half a century, but now many citizens are being fined, forced to go through lawsuits, or facing jail time for voicing their opinions publicly.

How is it that fundamental democratic rights like freedom of speech and freedom of press seem more threatened than ever before, as Myanmar is supposedly working their way through a democratization period?

Five decades after their coup d’état, the military junta in Myanmar accepted a new constitution in 2008, which they called “a roadmap to democracy”.

Following the new constitution, the military government began releasing political prisoners in 2010. These included some of their biggest opponents, the National League for Democracy (NLD)-leaders, whom upon release were allowed to re-group their party and run in upcoming elections. One year later, the country’s first national human rights commission was established, allowing people to join labor unions and advocate their rights. By 2012, the economy was opened up to the world market, currency exchange rates were pegged, and a series of unprecedented policies were put in place, allowing for foreign direct investment and the initiation of anti-corruption efforts.

Finally, in 2015, the people of Myanmar elected the majority of their government for the first time in over half a century. It was indeed apparent that Myanmar had entered a new era of democratization.

To the relief of Myanmar’s private media organizations, government leaders also began calling for the abolishment of media censorship during this new transition of democracy, describing it as incompatible with democratic principles. During previous decades of authoritarian rule, independent journalists in Myanmar had either been operating ‘on eggshells’, or fled the country.

Many private media organization leaders in Myanmar are former student protesters from the famous pro-democracy movement in the late 1980s, 8888 Uprising, and started their independent media organizations as refugees abroad during the 1990s. The new promises of democracy and freedom of the press within recent years made some of these exiled media organizations return to their homeland, such as Democratic Voice of Burma (operating from Norway), Mizzima (operating from India), and Irrawaddy (operating from Thailand).

Following Myanmar’s first successful democratic general election in 2015, the country’s new civilian government assumed office on April 1, 2016, after half a century of military dictatorship. Even more encouraging of change still, was that the new government was headed by the military’s biggest political opponent, NLD, with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi as its leader.

In 2017, the Ministry of Information gave unprecedented national broadcasting licenses to private media operators. International rankings, such as Reporters Without Borders (RSF), were beginning to recognize Myanmar’s improving freedom of the press. In their Press Freedom Index, RSF promoted Myanmar with twelve points from 2016 to 2017, making it the country with third best freedom of the press in its geographic region.

Myanmar has indeed shown multiple democratic developments, such as the improvement of a free press. Nonetheless, if only assessing the steps moving forward, a significant piece of the puzzle is being left out to correctly depict the conditions on the ground. Twenty months after the National League for Democracy took over majority seats in the government, evidence suggests that the military’s 2008 Constitution has allowed Myanmar to take one step forward, but also two steps back.

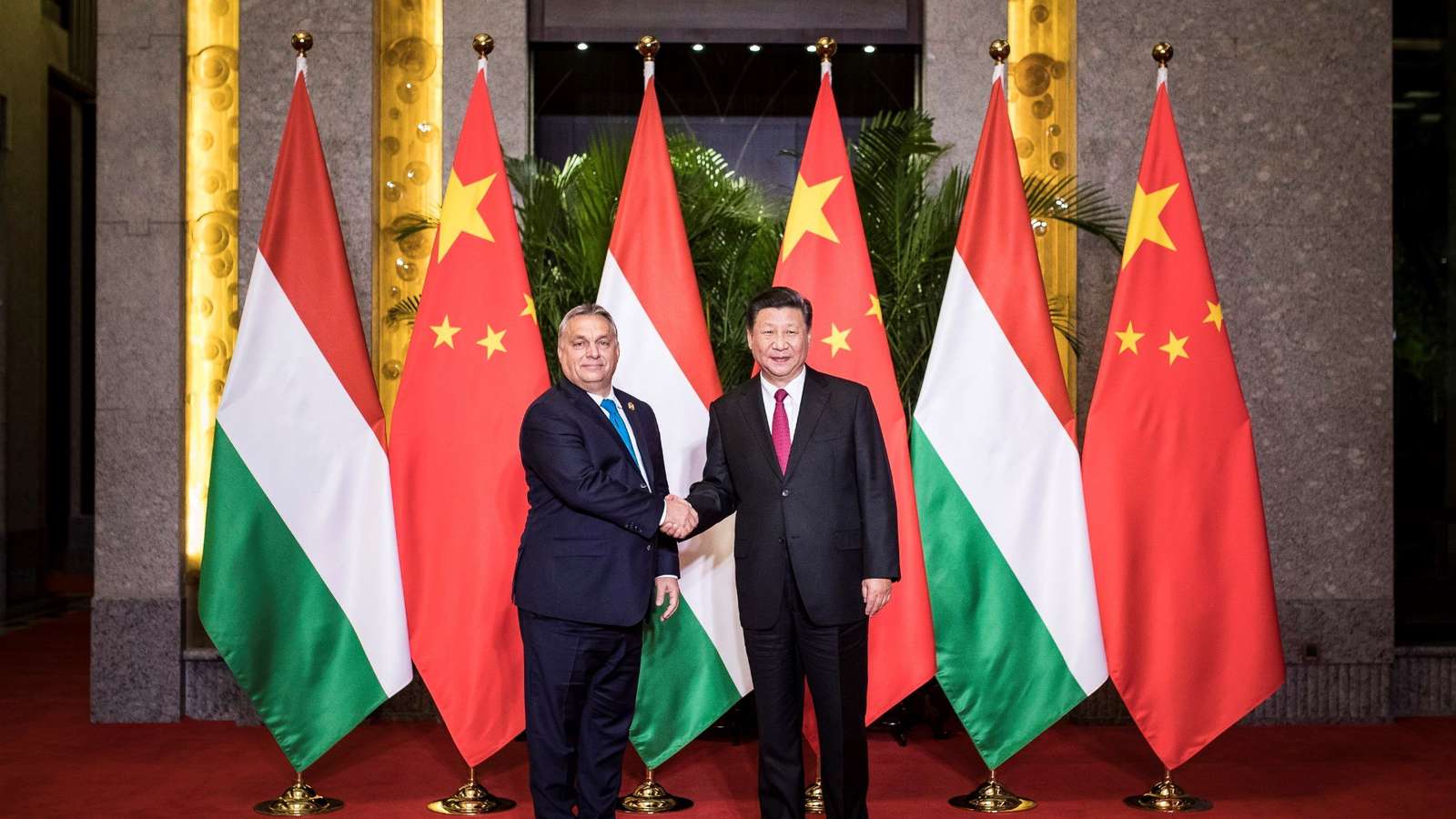

Photos taken by Elisa Chavez

State-owned media continue to be fully funded by the government whilst private media organizations do not receive any subsidies. Daily state-owned newspapers, therefore, control 95 percent of the newspaper market, with their advantage in receiving state-sponsored financial support. This makes it very difficult for private media organizations to survive, because they have to operate and compete within the same market as state-owned media, but under very different circumstances. Even the biggest private media operators are still depending on external financial support to survive.

Furthermore, one Malaysian and one Singaporean national are currently facing three years of prison for filming parts of Myanmar’s capital Naypyitaw with a drone. They claimed to have obtained all the necessary permits in advance, but have already spent two months in jail under arbitrary arrest. In April, a National League for Democracy-member was convicted to six months in jail for criticizing the military’s Commander-in-Chief on Facebook. That same month, a news weekly publisher who had publicly criticized military generals was stabbed to death. In May, two more journalists were subjects to a defamation suit by the military. They ended up spending two months in jail and were only released after paying a bail of 10 million kyats ($7400 USD). In June, three independent journalists who had covered a drug-burning ceremony by one of Myanmar’s ethnic armed organizations were arrested for unlawful association with an ‘illegal group.’ In September, a journalist was prosecuted under defamation laws for criticizing a Buddhist monk for spreading hate speech about Muslims in Myanmar. The list goes on.

In 2017, more representatives of the free press, and even ordinary citizens have been sued and imprisoned for exercising their freedom of speech and freedom of press, than during the previous authoritarian regime. As a result, self-censorship among journalists is growing.

The most used charge is the controversial paragraph 66(d) on defamation in the Telecommunication Law from 2013. This law has been systematically used to silence public criticism towards human rights abuse allegations committed by the military, or criticism towards Buddhist leaders who direct hate speech and encourage violence against Muslim minorities. Military travel restrictions for independent media is also an ongoing problem, in terms of the press’ ability to accurately report on alleged human rights abuses by both military and ethnic armed organizations in the different regions of the country. Only state-owned media are allowed by the military to travel to high-tension areas, as their news reports contents are controlled by the military.

Confronted with a spectrum of economic, legal, and political challenges, most independent media leaders are now wondering if it was a mistake to move their operations back to Myanmar.

The country’s civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, is taking a lot of heat for Myanmar’s stumbling democratization process. Disappointment is growing among independent journalists and their supporters in the world press freedom network for the country’s lack of protection of basic democratic principles, like freedom of speech and freedom of the press, especially since some of the independent media leaders who were student protest leaders in the 1980s were Aung San Suu Kyi’s biggest support groups domestically during her years as a political prisoner. It is hard not to take it personally that she has not given them the protection they expected, now that she is in power.

If she and her NLD-party leaders, however, are unable to pass reforms in parliament without military support, nor able to assemble support from the judiciary branch, her power to create change with the current constitution becomes terribly limited.

Despite allowing for a number of democratic developments, the 2008 Constitution still grants the military 25 percent of seats in both upper and lower houses of the parliament, making it practically impossible to pass legal reforms without military support. Furthermore, the constitution does not guarantee an independent judiciary branch. The record of imprisoned and sued independent journalists testify to that fact. Neither judges nor the judiciary institutional infrastructure have undergone any change since democratic reforms began in 2010, meaning that the judiciary branch remains heavily politicized and controlled by the military.

Many international news organizations today refer to Aung San Suu Kyi as the de facto leader of Myanmar. Reviewing trends in how the military systematically controls the legislative process, evidence suggests that she is in fact not the de facto leader in Myanmar today.

Making the situation for free speech and a free press even more difficult, an extraordinary explosion of information and communication technologies (ICT) in Myanmar has given millions access to public platforms where they can voice their opinions – for better or worse. Before the economy opened up to the world in 2012, only North Korea had fewer cell phones than Myanmar. A short five years later, the increase in mobile subscriptions has been unparalleled. At the end of January 2017, there were 54 million registered mobile phones in a country of 52,8 million people. Authorities estimate that about 89 percent of the population is now online.

Most of the mature democracies in the world today did not have to deal with having almost its entire population online, with access to express opinions on public platforms, during democratic transitions. It is not hard to imagine how a country with a considerable history of suppressive, hermetic rule, long-standing traditions of ethnic tensions, and an unprecedented ICT-explosion, has come to struggle with navigating the fine line between freedom of speech and hate speech. What is more, the judicial branch is still heavily politicized, with defamation laws being too easily manipulated by the military.

The very design of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution was intended to initiate a transitional period, a phasing out of autocracy to democracy, but it seems that it is also limited to only that initial phase. Trends today show how the 2008 Constitution is now strangling Myanmar’s ability to advance from being a democracy in transition into being a complete thriving democracy.

For a democratic society to be responsible and powerful, it must be informed. Freedom of speech and a free press are cornerstones of a functioning democracy. As watchdogs, they help inform the public, empowering them with knowledge with which they can hold those in positions of power accountable.

The limitations to her powers are plentiful, but Aung San Suu Kyi seems to forget she has another player on her team that could be a significant asset in advancing change for free speech and a free press. Civil society has gained a growing presence in Myanmar since the beginning of the democratic reforms, and their advocacy, if strong enough, could be a substantial support group for the democratization movement to overcome some of the hinders it currently faces.

If Aung San Suu Kyi prioritizes a keener investment in the strengthening of civil society, she might very well gain stronger support in domestic and international activism for the safeguarding of basic democratic rights in Myanmar. Then, if a stronger civil society can act as government watchdogs, temporarily filling the void of a free press as well as launching domestic and international activist movements for the safeguarding democratic rights, the creation of a virtuous cycle enabling the development of a free press is more likely. Stronger domestic and international grassroots movements, advocating for the protection of democratic rights like freedom of speech and freedom of press, might just create the right kind of noise and pressure on the military to gracefully give up their last stronghold on power, and allow for a genuine democratization to foster a free press in Myanmar.

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors for Spring 2025! - February 26, 2025

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors for Fall 2024! - August 20, 2024

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors! - February 19, 2024