Senior Editor Joel Petersson Ivre looks back at a decade that promised to deliver humanity to greatness but only delivered fast-food.

Although we are leaving the 2010s behind us, I cannot shake the feeling that it was the decade that left us behind.

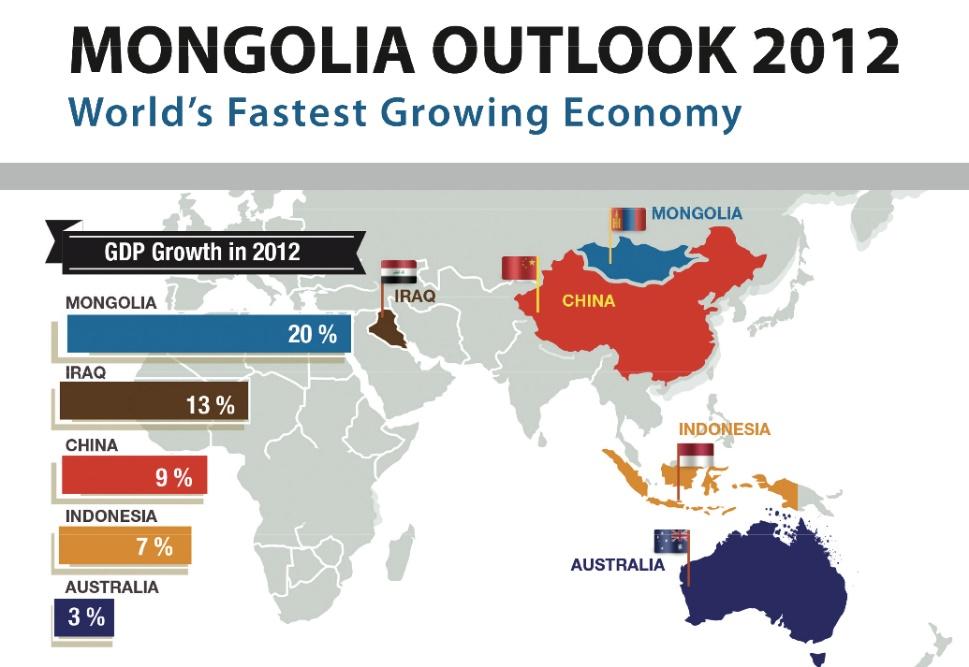

The second decade of the millennium produced more information than all of human existence before it. It created more prosperity, produced more smartphones, and decreased global infant mortality rates.

It also lit more forest fires, consumed more coal, and displaced more refugees.

Whatever happened before this decade, it can be comfortably said that if it is still happening, it is happening faster. The 2010s was the decade of acceleration.

Tomas Friedman said that 2007 was the year that unleashed the global technological revolution. It was the year that launched Facebook, but more importantly, the smartphone platform that made “content” the number one online currency. Everyone could now create content, consume content, become content.

The explosion of online content was typical of a decade when creativity became synonymous with extracting added value from increasingly trivial corners of the modern human experience. Big Data, AI, machine learning, and the Internet of Things became buzzwords for technology that supporters said would bring the human experience to the next level. But so far, that industry has mostly provided over-engineered juice presses and “smart” homes as playthings for the very same people who coded them.

You may object that this is an overly simplified and unfair assessment of the so-called “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” but it is undeniable that technological breakthroughs are making a utopian promise that they have so far failed to fulfill.

Technological advances happen so fast that by the time lawmakers have finished writing the rules of the game, the game has already changed. For the tech billionaires staking out the new world, the only rules they need are the ones, they make for themselves. Look no further to Mark Zuckerberg’s absolute bewilderment at the suggestion that anyone would use his platform to facilitate election-fraud and genocide.

The problem is worse in authoritarian states (also on the rise, by the way) where the law isn’t worth the paper it’s written on in the first place. Chinese authoritarianism has forged the shiny tools of the Fourth Industrial Revolution into instruments of the Second Cultural Revolution. Compared to only a decade ago, China’s ability to spy on its citizens is now unprecedented and unrivaled in the world.

The class divide between the common folk, tech billionaires, and the governing elites that preside above them, is the constant of this otherwise transformative decade. The eerie cyberpunk conclusion of the decade is witnessing protestors across the world defiantly aiming their laser pens at drones, helicopters, and security cameras. These protests are the inevitable fruits of resentment that were sown but never reaped by the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Umbrella Movement, and the global protests after the failed Copenhagen Summit in 2009. These movements are diverse in the target of their resentment but share the sentiment that significant structural changes, particularly economic inequality, are outpacing their ability to handle them.

The quickening pace of inequality was well-illustrated by the French economist Piketty, who argued that inequality occurs when interest on capital is higher than economic growth. In simple terms, Piketty’s thesis is that those who produce actual material value cannot accumulate wealth at the same pace as those who already have wealth sitting in a bank account. The result is a pooling of society’s capital among the richest.

Overshadowing all the other accelerations of late-stage capitalism symptoms is the escalating climate emergency. It is the crowning phenomena of the decade of acceleration, the one which most urgently demands a solution, and the one which is least likely to receive one. In the light of Australian forest fires, other accelerating trends pale in comparison. Across the world, high-school students take to the streets to express their frustration at the world’s inaction in the face of overwhelming evidence. They belong to the second generation that will grow up poorer than the one before it.

In the final year of the decade of acceleration, the resentment and frustration have seeped into some of the most acclaimed pieces of pop-culture. South Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, like the rest of the director’s filmography, depicts not just class struggle, but class warfare. The theme is even more overt in The Joker, where Joaquin Phoenix executes three businessmen in a subway cart, igniting city-wide riots.

In Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You, two thralls of the gig-economy struggle to make ends meet until they no longer can. Indeed, I’ll allow myself to make one personal concluding remark about the decade of acceleration: the one spawn of this decade that I resent the most is the so-called gig-economy. With a glossy polish of social network and hollow promises of “freedom to work wherever you want,” websites underpinned by algorithms and exploitative business models pass along menial tasks to the new cyber proletariat, which it has to complete for as little as five dollars apiece. Ridesharing and delivery services like Uber and Foodora are more visible but no less exploitative tools of the gig-economy to dress up minimum-wage labor in fancy smartphone apps and call it “innovation.”

I’m there, too. Every night I sit in front of a computer screen that asks me, “Which color best describes your personality?” or “What are 5 reasons to love you?” I get 540 dollars per month to translate these inane quizzes to my native language. Sometimes I translate what I swear is the same file for three days in a row. Upon closer inspection, the dispatcher, located somewhere else in a different time zone, has changed the order of three words here or replaced one sentence there. Somewhere in the vast void of cyberspace, an algorithm is feeding on these minute differences, calculating which one produces the most engagement.

Before I close my laptop, I send another CV — every verb carefully selected from an online list of “action verbs” — to another unpaid internship. Then I throw my uneaten delivery chicken in the trash.

- The Decade of Acceleration - December 31, 2019

- Episode 6: Moving Cities – Indonesia moves its capital - October 8, 2019

- China turns 70 and asks: “Maybe I’m getting too old for this?” - September 27, 2019