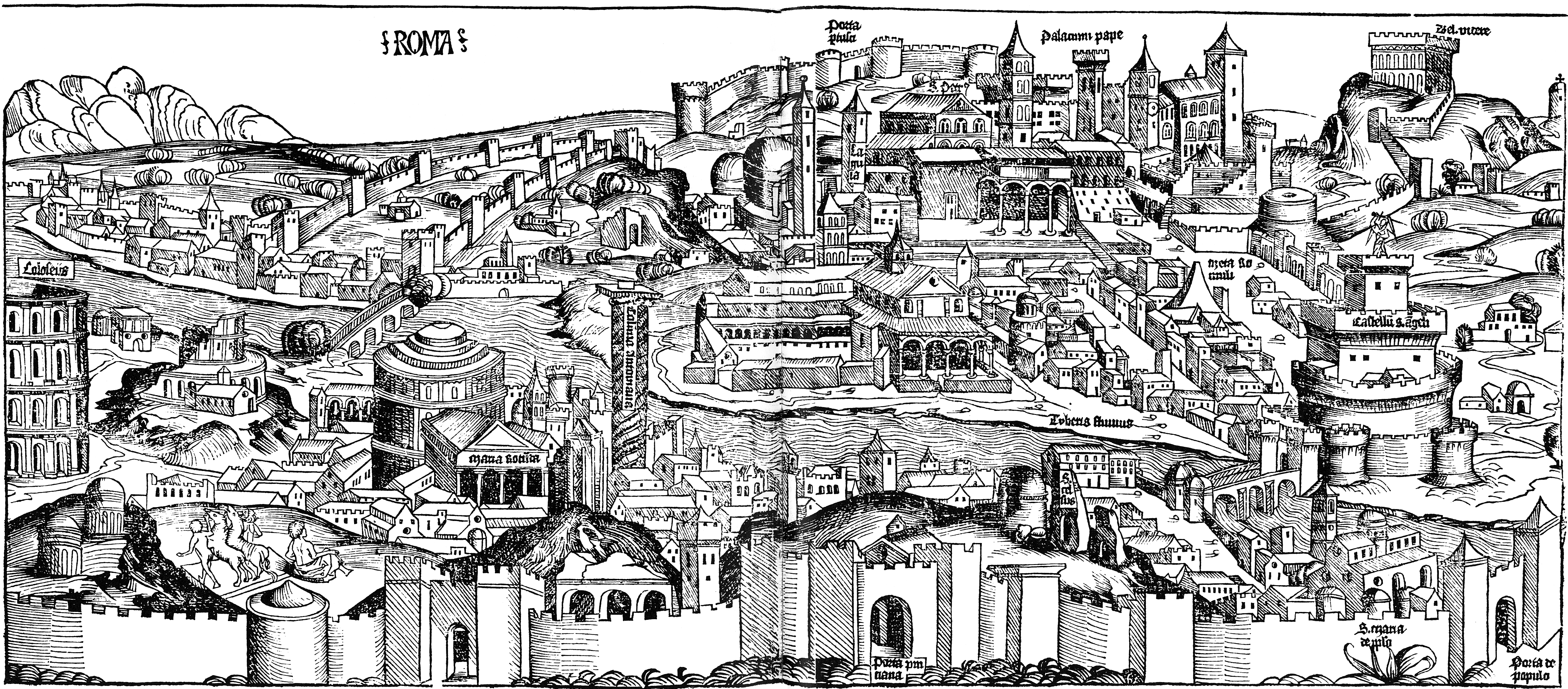

Rome was not built in a day, the saying goes. Yet the idea of a rapid “fall of Rome” seems to be commonly accepted: non-Roman barbarian “others,” taking advantage of Roman weakness, pouring across the borders and tearing down civilization, leaving Europe in a cultural backwater for the next millennium. This is an image which easily captures the imagination, and it fits into the general narrative of the Middle Ages as a generally backward, barbaric era. It has unrelentingly maintained its grip on minds, child and adult alike, even over the protests of professional historians who frown upon the use of that demeaning, and inaccurate, term “the Dark Ages.” Such a pessimistic view of an entire thousand plus years of European history is in fact the result of successful propaganda by Renaissance-era thinkers, who sought to emphasize their achievements by contrasting their time period with the alleged barbarism and darkness of the centuries before them and signaling a return to the cultural and intellectual glory of classical Europe (hence a “rebirth”). And the beginning of all the darkness of the Middle Ages begins with the so-called “fall of Rome,” precipitated by the mass movements of barbarian tribes who allegedly did not adhere to “Roman ways” and ended up destroying the empire.

But the real question that needs to be asked is not “why did Rome fall?” but rather “did Rome fall at all?” And the argument can be convincingly made that it did not, in fact. Rather, the migrations that took place between the fifth to the eighth centuries across Europe should not be seen as “barbarian invasions” but rather the incorporation of diverse (not just a monolithic “Germanic tribe”) peoples on the periphery into the Roman world. Rome never “fell” – it was instead fundamentally changed by the active participation of people on both sides of the borders, including the Roman authorities themselves, who used techniques from land distribution to tax shares.

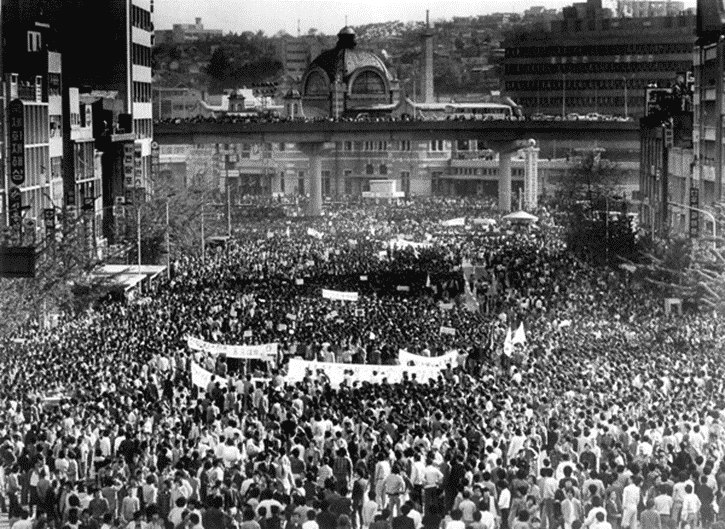

But the idea of the “fall of Rome” is difficult to let go. The tragedy of the fall of a cultured civilization makes for a good story charged with pathos. And, perhaps more importantly, the narrative speaks to many contemporary fears of the “other” and the dangers that mass migrations are deemed to pose to one’s own society. Rather than offering a direct instructive example, of course, history is said to teach by analogy, and perhaps in a related vein of thought, we need to be wary of the images we hold about mass migrations and movements of people across borders. The recent tragedy in Paris has increased scrutiny on the refugees entering into Europe and sparked debates about their identity. The terms used in such discussions are politically charged. In referring to the ongoing events, media reports split on their use of either “migrant crisis” or “refugee crisis.” These terms, though to the unsuspecting may initially seem interchangeable, reveal a deeper, serious disagreement over the nature of the people who are coming into Europe: are they migrants, a more general term that may also refer to those seeking better economic conditions to improve their livelihoods, or are they refugees, fleeing persecution and bodily harm in their home countries? For the xenophobic elements, of course, the distinction is not important – whether migrant or refugee, they pose a threat to Europe and need to be kept out.

But those that seek to preserve some idea of a pure and original “Europe” against an alleged threat from immigrants and refugees are deeply misled, and an attempt to “keep them out” is both infeasible and bound to be fruitless. Movements of people across countries, across borders, across any space, are some of the most powerful forces driving history, helping to promote cross-cultural contacts, innovation, and political, economic, and societal developments. The movements in Europe in the fifth through to the eighth centuries did not destroy the civilized world and Roman culture—rather, it brought large groups of people in greater contact with one another and fundamentally altered the face of Western Europe.

Contrary to the Renaissance view, the Middle Ages saw the rise of universities as we know them today, the development of what would become our modern-day Romance languages, and vibrant advances in art and architecture that we can still admire. This is certainly not to whitewash the darker aspects of the period, in which some historians see the beginnings of Europe as a persecuting society, targeting not only Muslims and Jews but also Christian religious minorities, lepers, and homosexuals.

But even as we note and decry these aspects, we should be careful not to descend into the condescending attitude towards the past that characterized Renaissance views of earlier centuries and that still remains with us today – the notion that somehow we in our own time period are so evolved and intelligent that we have the right to sneer on the obvious stupidity of those that came before us. Considering the xenophobic and racist parties across Europe gaining greater ground, state governors in the U.S. declaring that they will refuse to accept any refugees, and the many instances of systematic oppression around the world, it is not apparent that we ourselves are any better. We should be so lucky to not be harshly judged by our descendants as being on the wrong side of history.

By Gene Kim

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors for Spring 2025! - February 26, 2025

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors for Fall 2024! - August 20, 2024

- NOVAsia Is Hiring: Call For Applications and Contributors! - February 19, 2024